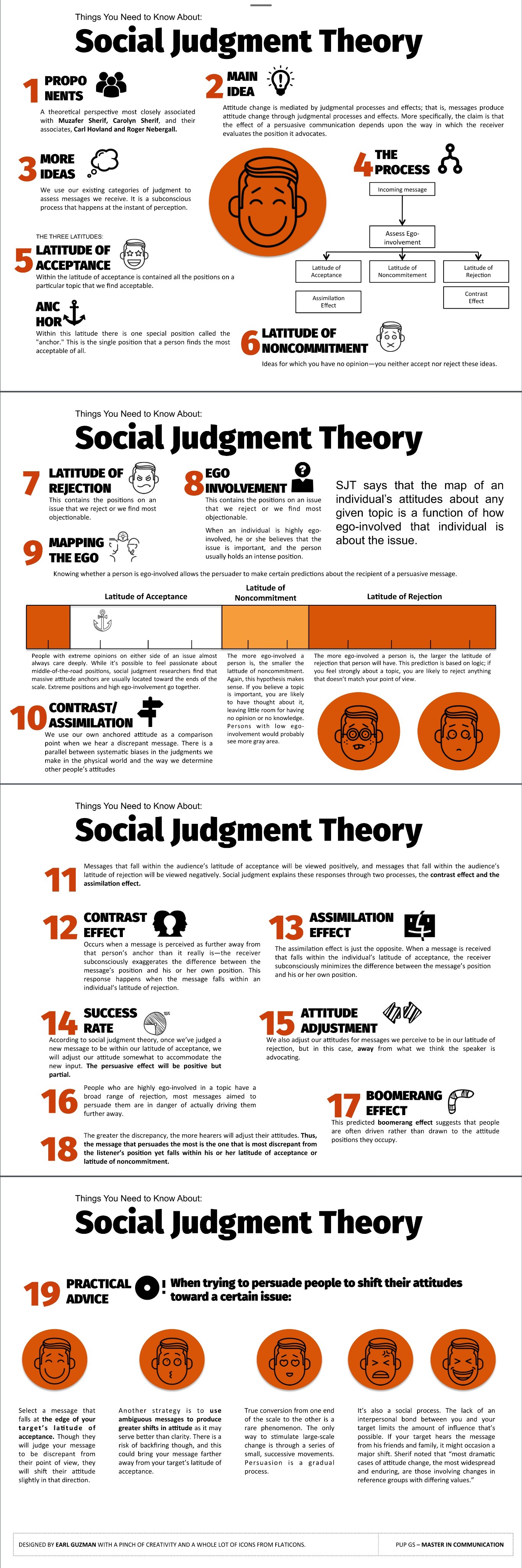

Social Judgement theory proposes the idea that persuasion is a two-step

process. The first step involves individuals hearing or reading a message

and immediately evaluating where the message falls within their own

position. The second step involves individuals adjusting their particular

attitude either toward or away from the message they heard.

Individuals have three zones in which they accept or reject specific

messages or attitudes. The latitude of acceptance zone is where

individuals place attitudes they consider acceptable. The latitude of

rejection zone is where individuals place attitudes they consider

unacceptable or objectionable. The latitude of noncommitment is where

people place attitudes they find neither acceptable nor rejectable.

Social Judgement Theory - Persuasion Context

https://www.uky.edu/~drlane/capstone/persuasion/socjud.htm

Social Judgement Theory - Claims that on almost every topic, each person has an anchor point, a latitude of acceptance, a latitude of noncommitment, and a latitude of rejection that they believe about the topic. Depending on how differentiated the person’s opinions are on a single topic, it can be more or less difficult to changed the already formed opinion. According to social judgment theory, once we’ve judged a new message to be within our latitude of acceptance, we will adjust our attitude somewhat to accommodate the new input. If the message agrees with our view points, it is easy to get further wrapped up into your opinion. On the other hand, if the message you listen to says something that opposes your opinion, you are much less likely to drastically change your opinion. In some case, you may feel more drawn to the side that the message is opposing. A big part of the acceptance of a message is the source that it is coming from. The lack of an interpersonal bond between [people] limits the amount of influence that’s possible.

https://blogs.baylor.edu/brianna_gutierrez/2018/02/13/week-5-blog-post-social-judgment-theory/

Social judgment theory was developed by psychologist Muzafer Sherif, with significant input from Carl I. Hovland and Carolyn W. Sherif. Rooted in judgment theory, which is concerned with the discrimination and categorization of stimuli, it attempts to explain how attitudes are expressed, judged, and modified. The theory details how attitudes are cognitively represented, the psychological processes involved in assessing persuasive communications, and the conditions under which communicated attitudes are either accepted or rejected. It offers a commonsense plan for inducing attitude change in the real world.

There are five basic principles in social judgment theory. The first asserts that people have categories of judgment with which they evaluate incoming information. When an individual encounters a situation in which he or she must make a judgment, a range of possible positions can be taken in response. For example, if an individual is asked to make a monetary contribution to a charity, the possible positions range from “absolutely not” to “most certainly.” Along this inclusive continuum there are categories of positions that an individual may find acceptable or unacceptable, and also a range for which no significant opinion is held. These ranges are referred to as the latitude of acceptance, the latitude of rejection, and the latitude of noncommittment, respectively. An individual’s most preferred position, located within the latitude of acceptance, is referred to as the anchor.

The second principle states that as people evaluate incoming information,

they determine the category of judgment, or latitude, to which it belongs.

In the above-mentioned example, individuals with a favorable view of the

charitable cause would most likely place the request for a donation within

the latitude of acceptance. Conversely, those who hold an unfavorable view

of the charitable cause will locate their attitude within the latitude of

rejection. Those with no significant opinion either way will locate it in

the latitude of noncommitment.

The third principle asserts that the size of the latitudes is determined by

the level of personal involvement, or ego-involvement, one has in the

issue at hand. People may or may not have opinions regarding the

communicated information, and this will affect whether or not the persuasive

message is accepted or rejected. These same opinions (or their lack) also

affect the size of latitudes. The higher the level of ego-involvement, the

larger the latitude of rejection becomes. For instance, an individual who is

solicited for a donation to a cancer society will have a smaller latitude of

acceptance if his or her mother suffers from cancer, as compared to someone

who has no personal connection to the malady. For that individual,

contributing to the charity is imperative, and any other response is

unacceptable. Therefore, the latitude of acceptance and noncommitment will

be small compared to the latitude of rejection.

Principle four states that people distort incoming information to fit their categories of judgment. When presented with a persuasive message that falls within the latitude of acceptance, and is close to the individual’s anchor, people will assimilate the new position. That is, they will perceive the new position to be closer to their attitude than it actually is. When the persuasive message is relatively far from the anchor, however, people tend to contrast the new position to their own, making it seem even more different than it actually is. In both cases, individuals distort incoming information relative to their anchor.

These distortions influence the persuasiveness of the incoming message. If the message is too close to the anchor, assimilation will occur and it will be construed to be no different than the original position. If contrast occurs, the message will be construed to be unacceptable and subsequently rejected. In both cases, social judgment theory would predict that attitude change is unlikely to occur.

The fifth principle asserts that optimal persuasion occurs when the discrepancies between the anchor and the advocated position are small to moderate. In such cases, assimilation or contrasting will not occur, allowing for consideration of the communicated message. Under these conditions, attitude change is possible.

A major implication of social judgment theory is that persuasion is difficult to accomplish. Successful persuasive messages are those that are targeted to the receiver’s latitude of acceptance and discrepant from the anchor position, so that the incoming information cannot be assimilated or contrasted. The receiver’s ego-involvement must also be taken into consideration. This suggests that even successful attempts at persuasion will yield small changes in attitude.

Principle 1. We have categories of judgment by which we evaluate persuasive positions.

Consider this example. The topic is ” Should We Increase Teacher Pay?” The range of positions one could take on this topic might look something like this:

- It is absolutely essential that teachers’ pay should be increased.

- It almost certain from many angles that teachers’ pay should be increased.

- It is highly probable that things would be better if teachers’ pay was increased.

- It is possible that it would be better if teachers’ pay was increased.

- It is difficult to say whether teachers’ pay should be increased.

- It is possible that it would be better if teachers’ pay was not increased.

- It is highly probable that teachers’ pay should not be increased.

- It is almost certain from most angles that teachers’ pay should not be increased.

- It is absolutely essential that teacher’s pay not be increased.

These nine statements appear to express a reasonable range of pro- to anti- positions a person could take on this topic. Now, according to Social Judgment Theory, we can categorize each position into one of three zones:

- Latitude of acceptance (zone of positions we accept);

- Latitude of non-commitment (zone of positions we neither accept nor reject);

- Latitude of rejection (zone of positions we reject).

Within the latitude of acceptance is contained all the positions on a particular topic that we find acceptable. For many teachers the first two or three statements in our example are probably acceptable and hence would fall into their latitude of acceptance. Within this latitude there is one special position called the “anchor.” This is the single position that a person finds the most acceptable of all. It may be the most extreme position (“absolutely essential”), but the anchor could also be a milder position (“highly probable”).

At some border point, we no longer accept some position, but we don’t reject it either. We are now in the latitude of non-commitment. This contains things about which we have no real opinion. With our example, it is probable that many teachers would rate the middle position (“difficult to say”) as being in their latitude of non-commitment. Perhaps one surrounding statement might also fall into this latitude. These are simply the positions that are neutral for the person.

As we move out of the latitude of non-commitment, we reach the second border. As we cross this border we begin to enter the latitude of rejection. This contains the positions on an issue that we reject. In our running example, most teachers would doubtless find the “anti” pay raise positions as unacceptable and place them in the latitude of rejection.

The next question is, how do we use these categories?

Principle 2. When we receive persuasive information, we locate it on our categories of judgment.

For example, if a very heavy object was used as the standard in assessing weight, then the other objects would be judged to be relatively lighter than if a very light object was used as the standard. The standard is referred to as an "anchor". This work involving physical objects was applied to psychosocial work, in which a participant's limits of acceptability on social issues are studied. Social issues include areas such as religion and politics...

...One of the ways in which the SJT developers observed attitudes was through the "Own Categories Questionnaire". This method requires research participants to place statements into piles of most acceptable, most offensive, neutral, and so on, in order for researchers to infer their attitudes. This categorization, an observable judgment process, was seen by Sherif and Hovland (1961) as a major component of attitude formation. As a judgment process, categorization and attitude formation are a product of recurring instances, so that past experiences influence decisions regarding aspects of the current situation. Therefore, attitudes are acquired.

Latitudes of rejection, acceptance, and noncommitment

Social judgment theory also illustrates how people contrast their personal positions on issues to others' positions around them. Aside from having their personal opinion, individuals hold latitudes of what they think is acceptable or unacceptable in general for other people's view. Social attitudes are not cumulative, especially regarding issues where the attitude is extreme. This means that a person may not agree with less extreme stands relative to his or her position, even though they may be in the same direction. Furthermore, even though two people may seem to hold identical attitudes, their "most preferred" and "least preferred" alternatives may differ. Thus, a person's full attitude can only be understood in terms of what other positions he or she finds acceptable or unacceptable, in addition to his or her own stand.

Sherif saw an attitude as amalgam of three zones or latitudes. There is the latitude of acceptance, which is the range of ideas that a person sees as reasonable or worthy of consideration; the latitude of rejection, which is the range of ideas that a person sees as unreasonable or objectionable; and, finally, the latitude of noncommitment, which is the range of ideas that a person sees as neither acceptable nor questionable.

These degrees or latitudes together create the full spectrum of an individual's attitude. Sherif and Hovland (1961) define the latitude of acceptance as "the range of positions on an issue ... an individual considers acceptable to him (including the one 'most acceptable' to him)" (p. 129). On the opposite end of the continuum lies the latitude of rejection. This is defined as including the "positions he finds objectionable (including the one 'most objectionable" to him)". This latitude of rejection was deemed essential by the SJT developers in determining an individual's level of involvement and, thus, his or her propensity to an attitude change. The greater the rejection latitude, the more involved the individual is in the issue and, thus, harder to persuade.

In the middle of these opposites lies the latitude of noncommitment, a range of viewpoints where one feels primarily indifferent. Sherif claimed that the greater the discrepancy, the more listeners will adjust their attitudes. Thus, the message that persuades the most is the one that is most discrepant from the listener's position, yet falls within his or her latitude of acceptance or latitude of noncommitment.

Assimilation and contrast

Sometimes people perceive a message that falls within their latitude of rejection as farther from their anchor than it really is; a phenomenon known as contrast. The opposite of contrast is assimilation, a perceptual error whereby people judge messages that fall within their latitude of acceptance as less discrepant from their anchor than they really are.[12]

These latitudes dictate the likelihood of assimilation and contrast. When a discrepant viewpoint is expressed in a communication message within the person's latitude of acceptance, the message is more likely to be assimilated or viewed as being closer to person's anchor, or his or her own viewpoint, than it actually is. When the message is perceived as being very different from one's anchor and, thus, falling within the latitude of rejection, persuasion is unlikely, due to a contrast effect. The contrast effect is what happens when the message is viewed as being further away than it actually is from the anchor.

Messages falling within the latitude of noncommitment, however, are the ones most likely to achieve the desired attitude change. Therefore, the more extreme an individual's stand, the greater his or her latitude of rejection and, thus, the harder he or she is to persuade.

Ego involvement

The SJT researchers speculated that extreme stands, and thus wide latitudes of rejection, were a result of high ego involvement.[13] Ego involvement is the importance or centrality of an issue to a person's life, often demonstrated by membership in a group with a known stand. According to the 1961 Sherif and Hovland work, the level of ego involvement depends upon whether the issue "arouses an intense attitude or, rather, whether the individual can regard the issue with some detachment as primarily a 'factual' matter" (p. 191). Religion, politics, and family are examples of issues that typically result in highly involved attitudes. They contribute to one's self-identity.

The concept of involvement is the crux of SJT. In short, Sherif et al. (1965) speculated that individuals who are highly involved in an issue are more likely to evaluate all possible positions, therefore resulting in an extremely limited or nonexistent latitude of noncommitment. People who have a deep concern or have extreme opinions on either side of the argument always care deeply and have a large latitude of rejection because they already have their strong opinion formed and usually are not willing to change that. High involvement also means that individuals will have a more restricted latitude of acceptance. According to SJT, messages falling within the latitude of rejection are unlikely to successfully persuade. Therefore, highly involved individuals will be harder to persuade, according to SJT.

In opposition, individuals who have less care in the issue, or have a smaller ego involvement, are likely to have a large latitude of acceptance. Because they are less educated and do not care as much about the issue, they are more likely to easily accept more ideas or opinions about an issue. This individual will also have a large latitude of noncommitment because, again, if they do not care as much about the topic, they are not going to commit to certain ideas, whether they are on the latitude of rejection or acceptance. An individual who does not have much ego involvement in an issue will have a small latitude of rejection because they are very open to this new issue and do not have previously formed opinions about it.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Social_judgment_theory

Persuasion on the Move: A Progressive Primer in Social Judgment Theory https://theuncommonsenserevolution.com/persuasion-on-the-move-a-progressive-primer-in-social-judgment-theory/