of hereditary privilege, state religion, absolute monarchy, the divine right of kings and traditional conservatism with representative democracy and the rule

of law. Liberals also ended mercantilist policies, royal monopolies and other barriers to trade, instead promoting

free trade and marketization.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Liberalism

Liberalism originated out of the breakdown

of feudalism. The vacuum created by the collapse of feudalism was immediately filled up by the rise of capitalism and in the capitalist era of economy there arose liberalism. This, liberalism, we call, classical liberalism. The classical liberalism is not a separate form of liberalism or quite different from the basic nature and elements of liberalism —we call it a stage of liberalism.

2. The Debate Between the ‘Old’ and the ‘New’ 2.1 Classical Liberalism

Liberal political theory, then, fractures over how to conceive of liberty.

In practice, another crucial fault line concerns the moral status of private

property and the market order.

For classical liberals — ‘old’ liberals —

liberty and private property are intimately related. From the eighteenth

century to the present day, classical liberals have insisted that an

economic system based on private property is uniquely consistent with

individual liberty, allowing each to live her life —including employing her

labor and her capital — as she sees fit. Indeed, classical liberals and

libertarians have often asserted that in some way -

liberty and property

are really the same thing;

it has

been argued, for example, that:

all rights, including liberty rights,

— are forms of property —

others have maintained that property is itself

— a form of freedom —

A market order based on private property is thus seen as an embodiment of freedom (Robbins, 1961: 104).

Unless people are free to make contracts and sell their labour, save and invest their incomes as they see fit, and free to launch enterprises as they raise the capital, they are not really free.

Classical liberals employ a second argument connecting liberty and private property.

Rather than insisting that the freedom to obtain and employ private property is simply one aspect of people’s liberty, this second argument insists that private property effectively protects liberty, and no protection can be effective without private property.

Here the idea is that the - dispersion of power - that results from a free market economy based on private property protects the liberty of subjects against encroachments by the state. As F.A. Hayek argues, “There can be no freedom of press if the instruments of printing are under government control, no freedom of assembly if the needed rooms are so controlled, no freedom of movement if the means of transport are a government monopoly” (1978: 149).

Although classical liberals agree on the fundamental importance of private property to a free society, the classical liberal tradition itself is a spectrum of views, from near-anarchist to those that attribute a significant role to the state in economic and social policy (on this spectrum, see Mack and Gaus, 2004).

- At the libertarian end of the classical liberal spectrum are views of justified states as legitimate monopolies that may with justice charge for essential rights-protection services: taxation is legitimate if necessary and sufficient for effective protection of liberty and property.

- Further ‘leftward’ we encounter classical liberal views that allow taxation for public education in particular, and more generally for public goods and social infrastructure.

- Moving yet further ‘left’, some classical liberal views allow for a modest social minimum.(e.g., Hayek, 1976: 87).

Most nineteenth century - classical liberal economists endorsed a variety of state policies, encompassing not only the criminal law and enforcement of contracts, but the licensing of professionals, health, safety and fire regulations, banking regulations, commercial infrastructure (roads, harbors and canals) and often encouraged unionization (Gaus, 1983b). Although classical liberalism today often is associated with libertarianism, the broader classical liberal tradition was - centrally concerned with bettering the lot of the working class, women, blacks, immigrants, and so on. The aim, as Bentham put it, was - to make the poor richer, not the rich poorer (Bentham, 1952 [1795]: vol. 1, 226n). Consequently, classical liberals treat the leveling of wealth and income as outside the purview of legitimate aims of government coercion.

2.2 The ‘New Liberalism’

What has come to be known as ‘new’, ‘revisionist’, ‘welfare state’, or perhaps best, ‘social justice’, liberalism challenges this intimate connection between personal liberty and a private property based market order (Freeden, 1978; Gaus, 1983b; Paul, Miller and Paul, 2007). Three factors help explain the rise of this revisionist theory. First, the new liberalism was clearly taking its own distinctive shape by the early twentieth century, as - the ability of a free market to sustain - what Lord Beveridge (1944: 96) called a ‘prosperous equilibrium’ was being - questioned. Believing that a private property based market tended to be unstable, or could, as Keynes argued (1973 [1936]), get stuck in an equilibrium with high unemployment, new liberals came to doubt, initially on empirical grounds, that classical liberalism was an adequate foundation for a stable, free society. Here the second factor comes into play: just as the new liberals were losing faith in the market, their - faith in government as a means of supervising economic life - was increasing. This was partly due to the experiences of the First World War, in which government attempts at economic planning seemed to succeed (Dewey, 1929: 551–60); more importantly, this reevaluation of the state was spurred by the democratization of western states, and the conviction that, for the first time, elected officials could truly be, in J.A. Hobson’s phrase ‘representatives of the community’ (1922: 49). As D.G. Ritchie proclaimed:

be it observed that arguments used against ‘government’ action, where the government is entirely or mainly in the hands of a ruling class or caste, exercising wisely or unwisely a paternal or grandmotherly authority — such arguments lose their force just in proportion as the government becomes more and more genuinely the government of the people by the people themselves. (1896: 64)

The third factor underlying the currency of the new liberalism was probably the most fundamental: a growing conviction that, so far from being ‘the guardian of every other right’ (Ely, 1992: 26), - property rights foster an unjust - inequality of power. They entrench - a merely formal equality that in actual practice systematically fails to secure the kind of equal positive liberty that matters on the ground for the working class.

This theme is central to what is now called ‘liberalism’ in American politics, combining a 1 - strong endorsement of civil and personal liberties with

2 - indifference or even hostility to private ownership.

The seeds of this newer liberalism can be found in Mill’s On Liberty.

Although

- Mill

insisted that the ‘so-called doctrine of Free Trade’ rested on ‘equally

solid’ grounds as did the ‘principle of individual liberty’ (1963, vol. 18:

293), he nevertheless

- insisted that the - justifications of personal and economic

liberty were distinct. And in his Principles of Political Economy, Mill consistently emphasized

that it is an open question whether -

personal liberty can flourish without private property -

(1963, vol. 2; 203–210), a view that Rawls was to reassert over a century

later (2001: Part IV).

Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/liberalism/#ClaLib

What Is Classical Liberalism?

People - thought they only had such rights as government elected to give them. But - following the British philosopher John Locke, - Jefferson argued that it’s the other way around. - People have rights apart from government, as part of their nature. Further, people can form governments and dissolve them. The only legitimate purpose of government is to protect these rights.

It has become fashionable, especially on university campuses, to view the founding fathers as hypocrites because many were slave owners and they appeared to believe that women, slaves, Indians and other groups were not entitled to the same rights as white, male property owners.

Yet this attitude misses the forest for the trees. In 1776, the world was full of hypocrites. It was not full of people who believed in individual rights. In fact, outside of a handful of people, who mainly lived in America, no one in the world believed in classical liberalism. For example, many people at the time may have thought that slavery was distasteful. But almost no one in the world thought that you have a right not to be a slave.

Although many of our democratic institutions find their roots in ancient Greece and ancient Rome, in those societies slavery was a normal and natural part of everyday life. In ancient Greece, for example, slaves outnumbered non-slaves, with the average household owning as many as three or four. More than one-third of all the people living in ancient Rome were slaves.

The United States is the first government in the history of the world whose founding documents endorsed the idea of individual rights that

- are prior to the government’s founding - and that legitimize the government’s founding.

Once it was granted that some people have natural rights, it was inevitable

that

the idea

-

would spread to everyone else

- Good ideas have to start somewhere.

People who live in the United States today and who are not white, not male and not property owners nonetheless have the same rights as everyone else precisely because almost 250 years ago, a group of men went to war to defend the idea that they had rights.

People who call themselves classical liberals today have a more expanded view. But the basic idea of what a right is and the role of government in protecting it is the same concept that Jefferson and his contemporaries had.

At the time of the country’s founding, - classical liberals - did not make any important distinction between economic liberties and civil liberties. When they spoke of freedom of speech, they tacitly assumed a market free enough to allow a publisher to buy newspaper, ink and a printing press. When they spoke of freedom of assembly, they implicitly assumed people would be able to rent a hall to hold meetings.

In other words, they did not foresee that years later, communist governments would be able to suppress basic civil liberties through their control of economic resources. It’s as if they assumed that free minds and free markets would naturally go together.

Nor did they foresee that in the United States in the 20th century, - the distinction between economic liberty and civil liberty would become a political dividing line. Conservatives in the 20th century were more concerned with economic rights than civil rights. For liberals, the preference was reversed.

The - major difference between - 19th-century liberals and - 20th-century liberals - was that the former believed in - economic liberties - and the latter did not.

Twentieth century liberals believed that it was not a violation of any fundamental right for government to regulate where people work, when they work, the wages they work for, what they can buy, what they can sell, the price they can sell it for, etc. In the economic sphere, then, almost anything was fair game.

At the same time, 20th-century liberals continued to be influenced by the 19th-century liberalism’s belief in and respect for civil liberties. In fact, as the last century progressed, - liberal support for civil liberties grew - and groups like the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) began to proudly claim the label “civil libertarian.” Since liberalism was the dominant 20th-century ideology, public policy tended to reflect its beliefs.

By the end of the century, people had far fewer economic rights than they had at the beginning. But they had more civil rights.

( A change has begun ) to occur in the 21st century, however. Today, particularly on college campuses, many people who are left-of-center have ceased using the term “liberal” altogether and are asserting that - ( rights and obligations accrue to people as members of groups, not as individuals ) So, racial identity, ethnic identity, economic condition, sexual preference, etc., may create rights for people within a group that are not shared by those outside the group – for no other reason than the fact that the outsiders are outsiders. They reject the notion of individual rights across the board – both economic rights and civil rights. Unlike liberals, they believe that what a person may permissibly say or write or publish may differ – depending on what group they identify with.

This is clearly a collectivist notion of rights and I will briefly discuss the historical roots of this type of collectivist thinking below.

https://www.goodmaninstitute.org/about/how-we-think/what-is-classical-liberalism/

Britannica - Classical Liberalism

Although liberal ideas were not noticeable in European politics until the early 16th century, liberalism has a considerable “prehistory” reaching back to the Middle Ages and even earlier. In the Middle Ages the rights and responsibilities of individuals were determined by their place in a hierarchical social system that placed great stress upon acquiescence and conformity.

Under the impact of the slow commercialization and urbanization of Europe in the later Middle Ages, the intellectual ferment of the Renaissance, and the spread of Protestantism in the 16th century, the old feudal stratification of society gradually began to dissolve, leading to a fear of instability so powerful that monarchical absolutism was viewed as the only remedy to civil dissension.

By the end of the 16th century, the authority of the papacy had been broken in most of northern Europe, and rulers tried to consolidate the unity of their realms by enforcing conformity either to Roman Catholicism or to the ruler’s preferred version of Protestantism.

These efforts culminated in the Thirty Years’ War (1618–48), which did immense damage to much of Europe. Where no creed succeeded in wholly extirpating its enemies, toleration was gradually accepted as the lesser of two evils; in some countries where one creed triumphed, it was accepted that too minute a concern with citizens’ beliefs was inimical to prosperity and good order.

The ambitions of national rulers and the requirements of expanding industry and commerce led gradually to the adoption of economic policies based on mercantilism, a school of thought that advocated government intervention in a country’s economy to increase state wealth and power. However, as such intervention increasingly served established interests and inhibited enterprise, it was challenged by members of the newly emerging middle class.

This challenge was a significant factor in the great revolutions that rocked England and France in the 17th and 18th centuries—most notably the English Civil Wars (1642–51), the Glorious Revolution (1688), the American Revolution (1775–83), and the French Revolution (1789). Classical liberalism as an articulated creed is a result of those great collisions.

In the English Civil Wars, the absolutist king Charles I was defeated by the forces of Parliament and eventually executed. The Glorious Revolution resulted in the abdication and exile of James II and the establishment of a complex form of balanced government in which power was divided between the monarch, ministers, and Parliament. In time this system would become a model for liberal political movements in other countries. The political ideas that helped to inspire these revolts were given formal expression in the work of the English philosophers Thomas Hobbes and John Locke...

Liberalism and democracy

The early liberals, then, worked to free individuals from two forms of social constraint—religious conformity and aristocratic privilege—that had been maintained and enforced through the powers of government. The aim of the early liberals was thus to limit the power of government over the individual while holding it accountable to the governed. As Locke and others argued, this required a system of government based on majority rule—that is, one in which government executes the expressed will of a majority of the electorate. The chief institutional device for attaining this goal was the periodic election of legislators by popular vote and of a chief executive by popular vote or the vote of a legislative assembly.

But in answering the crucial question of who is to be the electorate, classical liberalism fell victim to ambivalence, torn between the great emancipating tendencies generated by the revolutions with which it was associated and middle-class fears that a wide or universal franchise would undermine private property. Benjamin Franklin spoke for the Whig liberalism of the Founding Fathers of the United States when he stated:

As to those who have no landed property in a county, the allowing them to vote for legislators is an impropriety. They are transient inhabitants, and not so connected with the welfare of the state, which they may quit when they please, as to qualify them properly for such privilege.

John Adams, in his Defense of the Constitutions of Government of the United States of America (1787), was more explicit. If the majority were to control all branches of government, he declared, “debts would be abolished first; taxes laid heavy on the rich, and not at all on others; and at last a downright equal division of everything be demanded and voted.” French statesmen such as François Guizot and Adophe Thiers expressed similar sentiments well into the 19th century.

As to those who have no landed property in a county, the allowing them to vote for legislators is an impropriety. They are transient inhabitants, and not so connected with the welfare of the state, which they may quit when they please, as to qualify them properly for such privilege.

John Adams, in his Defense of the Constitutions of Government of the United States of America (1787), was more explicit. If the majority were to control all branches of government, he declared, “debts would be abolished first; taxes laid heavy on the rich, and not at all on others; and at last a downright equal division of everything be demanded and voted.” French statesmen such as François Guizot and Adophe Thiers expressed similar sentiments well into the 19th century.

Despite the misgivings of men of the propertied classes, a slow but steady expansion of the franchise prevailed throughout Europe in the 19th century—an expansion driven in large part by the liberal insistence that “all men are created equal.” But liberals also had to reconcile the principle of majority rule with the requirement that the power of the majority be limited. The problem was to accomplish this in a manner consistent with democratic principles. If hereditary elites were discredited, how could the power of the majority be checked without giving disproportionate power to property owners or to some other “natural” elite?

Separation of powers

The liberal solution to the problem of limiting the powers of a democratic majority employed various devices. The first was the separation of powers—i.e., the distribution of power between such functionally differentiated agencies of government as the legislature, the executive, and the judiciary...

https://www.britannica.com/topic/liberalism/Classical-liberalism

In general, classical liberalism is a right-wing ideology and based upon

the values of political and economic individualism. This means that it

highly values individual freedoms and limited government intervention in the

lives of citizens. To fully understand the significance of these

individualistic values, it’s first important to understand the systems that

existed before. The development of classical liberalism at the time was a

revolutionary idea because Europe, had previously been based on the

following: feudalism, absolute monarchy, and mercantilism.

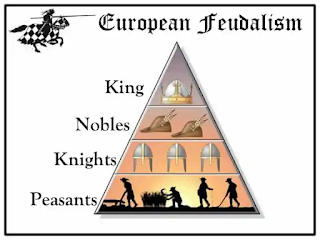

BEFORE CLASSICAL LIBERALISM

In short, feudalism was a class system common in European societies throughout the time period of the Middle Ages in which society was divided into a clear set of classes. For example, feudal societies were often structured with clergy as the top class, followed by the nobility and then the peasant class. Feudalism was often combined with absolute monarchy which was a form of government in which all authority rested in one single person; a king or queen. Under this system of government, the monarch had total control over society and made all of the decisions pertaining to the society. Countries that were based on feudalism and absolute monarchies usually practiced mercantilism as an economic system. In general, mercantilism is an economic system that was common throughout Europe during the Middle Ages and up to the 18th century. It was a system based on heavy government (monarch) intervention in the economy, and involved countries trying to maximize their exports and minimize their imports. The three systems of feudalism, absolute monarchy and mercantilism combined to make up a society that was based on a strong central government that controlled most aspects of life for their citizens of the country. This meant that average people in these societies lacked basic political and economic freedoms that we enjoy today in modern democratic countries.

Positives of Classical Liberalism

- As an ideology, classical liberalism is associated with the right-side of the economic and political spectrums because it favored limited government intervention in society, combined with individual rights and freedoms and the principle of rule of law.

- Previous to classical liberalism, European society was based primarily on absolute monarchs who ruled over their citizens as authoritarians. This means that the king or queen had total control over all aspects of society and did not provide their citizens with basic rights or freedoms.

- An important development of liberalism was the idea that all people contain certain natural rights. ...all people possessed some form of basic individual rights. ...there should be very little limits placed on people’s rights. For classical liberals these rights included: freedom of speech, freedom of religion, freedom of association, the right to vote, etc.

- The first major development of rights in American and European society were related to the American and French revolutions. In both, the people overthrew the monarchy that ruled over them and established basic sets of rights for themselves. ...It extended the right to vote to more people and ended the reign of brutal monarchs.

- The emergence of the ...rule of law protected citizens from the authoritarian rule of absolute monarchs. ...based on the idea that a country should be ruled by a distinct and clear set of laws instead of the individual rule of a singular person. ...all people are equal before the law, including the rulers. ...the development of rule of law ...limited the rule of the government and protected the security and well-being of individual people.

- On the economic spectrum, classical liberalism is considered to be a right-sided ideology that favors limited government intervention. Therefore, classical liberalism is based upon the principles of capitalism. In fact, classical liberal societies are considered to have been laissez-faire capitalism, meaning they favored as little government as possible.

Negatives of Classical Liberalism

- Since there is little or no government intervention in a classical liberal society, that is based on laissez-faire capitalism, the opportunity exists for the wealthy to exploit certain aspects.

- While limited government may be beneficial in promoting economic freedom and choice, it also has the ability to cause large income gaps in society. ...The lack of a government to protect the working class people meant that wealthy entrepreneurs could take advantage of the poor.

- Classical liberal societies ...often lead to higher levels of unemployment. The nature of a free market or laissez-faire economy is such that individuals cannot count on the government to protect or help them in a time of need. As such, most countries based on a free market economy have some level of unemployment. This means, that at some points a certain percentage of the population will be struggling with poverty and be unable to support themselves.

- Because the government does not intervene in a classical liberal society, monopolies may also form. A monopoly is when one corporation dominates and controls an entire industry. This is bad for consumers, because without the benefit of choice, the corporation would increase prices to whatever they wanted.

- Free market economies are usually reliant on the forces of supply and demand. While this provides a framework for economic freedom to exist it also creates a system of ‘boom and bust’ in the overall economy. ...often susceptible to changing economic conditions, which could be difficult to endure for many average consumers.

- Two prominent examples of exploitation ...in the time of the Industrial Revolution was the use of child labor and the degree of pollution. ...principles of classical liberalism ...allowed business owners to act without much government regulation. ...child labor was common ...and often the children suffered from horrible abuse and conditions. ...cities and towns suffered from horrible living conditions, in part due to pollution...

Therefore, while classical liberalism allows economic freedom, it struggles to handle societal problems related to exploitation.

Because of these negative aspects, classical liberalism societies began to transform throughout much of the 19th and 20th centuries. In general, countries such as England began to shift more left on the economic spectrum to include elements of socialism, which began to emerge in response to the horrible conditions present during the Industrial Revolution. As such, classical liberal societies shifted to the center of the spectrum and became modern liberal societies.

https://www.historycrunch.com/classical-liberalism.html

Definition of Classical Liberalism

Spawned by 18th-century thinkers like Adam Smith and John Locke, the politics of classical liberalism diverged drastically from older political systems that placed rule over the people in the hands of churches, monarchs, or totalitarian government. In this manner, the politics of classical liberalism values the freedom of individuals over that of central government officials.

Classical liberals rejected the idea of direct democracy—government shaped solely by a majority vote of citizens—because majorities might not always respect personal property rights or economic freedom. As expressed by James Madison in Federalist 21, classical liberalism favored a constitutional republic, reasoning that in a pure democracy a “common passion or interest will, in almost every case, be felt by a majority of the whole [...] and there is nothing to check the inducements to sacrifice the weaker party.”...

Classical Liberalism vs. Modern Social Liberalism

Modern social liberalism evolved from classical liberalism around 1900. Social liberalism differs from classical liberalism in two main areas: individual liberty and the role of government in society.

Individual Liberty

In his seminal 1969 essay “Two Concepts of Liberty,” British social and political theorist Isaiah Berlin asserts that liberty can be both negative and positive in nature. Positive liberty is simply the freedom to do something. Negative liberty is the absence of restraints or barriers limiting individual freedoms.

Classical liberals favor negative rights to the extent that governments and other people should not be allowed to interfere with the free market or natural individual freedoms. Modern social liberals, on the other hand, believe that individuals have positive rights, such as the right to vote, the right to a minimum living wage, and—more recently—the right to health care. By necessity, guaranteeing positive rights requires government intervention in the form of protective legislative and higher taxes than those required to ensure negative rights.

Role of Government

While classical liberals favor individual liberty and a largely unregulated free market over the power of the central government, social liberals demand that the government protect individual freedoms, regulate the marketplace, and correct social inequities. According to social liberalism, the government—rather than society itself—should address issues such as poverty, health care, and income inequality while also respecting the rights of individuals.

Despite their apparent divergence from the tenets of free-market capitalism, socially liberal policies have been adopted by most capitalist countries. In the United States, the term social liberalism is used to describe progressivism as opposed to conservatism. Especially noticeable in the area fiscal policy, social liberals are more likely to advocate higher levels of government spending and taxation than conservatives or more moderate classical liberals.

https://www.thoughtco.com/classical-liberalism-definition-4774941

Decentralization and the division of power have been the hallmarks of the history of Europe. After the fall of Rome, no empire was ever able to dominate the continent. Instead, Europe, became a complex mosaic of competing nations, principalities, and city‐states. The various rulers found themselves in competition with each other. If one of them indulged in predatory taxation or arbitrary confiscations of property, he might well lose his most productive citizens, who could “exit,” together with their capital. The kings also found powerful rivals in ambitious barons and in religious authorities who were backed by an international Church. Parliaments emerged that limited the taxing power of the king, and free cities arose with special charters that put the merchant elite in charge.

By the Middle Ages, many parts of Europe, especially in the west, had developed a culture friendly to property rights and trade. On the philosophical level, the doctrine of natural law — deriving from the Stoic philosophers of Greece and Rome — taught that the natural order was independent of human design and that rulers were subordinate to the eternal laws of justice. Natural‐law doctrine was upheld by the Church and promulgated in the great universities, from Oxford and Salamanca to Prague and Krakow.

As the modern age began, rulers started to shake free of age-old customary constraints on their power. Royal absolutism became the main tendency of the time. The kings of Europe raised a novel claim: they declared that they were appointed by God to be the fountainhead of all life and activity in society. Accordingly, they sought to direct religion, culture, politics, and, especially, the economic life of the people. To support their burgeoning bureaucracies and constant wars, the rulers required ever-increasing quantities of taxes, which they tried to squeeze out of their subjects in ways that were contrary to precedent and custom.

The first people to revolt against this system were the Dutch. After a struggle that lasted for decades, they won their independence from Spain and proceeded to set up a unique polity. The United Provinces, as the radically decentralized state was called, had no king and little power at the federal level...

https://www.libertarianism.org/publications/essays/rise-fall-renaissance-classical-liberalism

The Rise of Classical Liberalism

Cultural and Religious Revolutions

The English historian Lord Acton (1834-1902) wrote that: "Liberty is established by the conflict of powers". In mainland Europe, the authority of the Roman Empire in the West and of subsequent feudal lords and monarchs had been challenged by the rise of the Christian Church. They did not consciously develop free institutions, but the mutual limitations that they imposed on each other opened up the opportunity for greater personal freedom.

Two other historical events in Europe cemented the importance of individual freedom over state power. A key part of the cultural revolution that was the Renaissance, roughly between the fifteenth and seventeenth centuries, was the introduction of the printing press into Europe in 1450. This simple invention broke the elites" monopoly over science and learning, making knowledge accessible to ordinary individuals. No longer did anyone have to consult authorities for guidance and permission: they had the information on which to base their own choices.

The Protestant Reformation, sparked by Martin Luther in 1517, reinforced this further. It challenged the power of the Catholic Church, and raised the self-esteem of ordinary people by asserting that they could have direct, personal and equal access to God, without needing the intermediation of an elite priesthood.

All this served to raise the position and importance of the individual over the established institutions of power. In the countries where this greater freedom flourished most, art, industry, science and commerce flourished too.

Political revolution

Politically, things were also changing. A pro-freedom mass movement, the Levellers, swept over England in the 1650s. It was led by John Lilburne (1614-57), who insisted that people"s rights were inborn rather than bestowed by government or law. Arrested for printing unlicensed books (in defiance of the official monopoly), he appeared before the notorious Star Chamber, but refused to bow to the judges (insisting that he was their equal) or accept their procedures. Even in the pillory he continued to argue for freedom and equal rights, and inevitably he was imprisoned for his challenge to authority - as he would be several times more.

Lilburne became a popular anti-establishment figure. He petitioned for the end of state monopolies and spelt out what amounts to a bill of rights. This was taken further by Richard Overton (c. 1610-63), also imprisoned for refusing to acknowledge the judicial authority of the House of Lords, who called for a written constitutional "social contract" between free people whom he saw as having property in their own persons that could not be usurped by anyone else.

Curbing the power of monarchs

After the English Civil War (1642-51), the reigning monarch, Charles I, was put on trial and executed for high treason - a stark assertion of the limits on government authority. But the power relationship between king and Parlia- ment had already turned. The island nation of Great Brit- ain (as it had become) needed no standing army to protect itself against frequent invasions. So, unlike continental Europe, the monarch had no force that could be used to repress and exploit the public. Charles needed Parliament to agree to raise taxes for foreign wars.

This frustrated a jealous monarch and led to many conflicts. Among other things, Charles suspended Parliament, sought to levy taxes without its consent and attempted forcibly to arrest five of its most prominent members. He had broken the implicit contract with the people, by which their rights were secured.

The Glorious Revolution

After an interregnum (1649-60) under the dictatorship of Oliver Cromwell, the balance of authority was made evi- dent again when Charles"s son Charles II had to appease Parliament in order to return as king. When his successor, Charles"s second son, James II, was deposed, it was Parliament who invited William (the Dutch Prince of Orange) and Mary to the throne. The direction of authority, from people to monarch, could not have been clearer.

In 1689, William and Mary signed the Bill of Rights, an assertion of the rights and liberties of British sub- jects and a justification of the removal of James II on the grounds of violating those rights and liberties. It called for a justice system independent of monarchs, an end to taxation without Parliament"s consent, the right to petition government without fear of retribution, free elections, freedom of speech in Parliament and an end to "cruel and unusual punishments". It would directly in- spire another great classical liberal initiative, America"s own Bill of Rights, a century later.

John Locke (1632-1704)

John Locke drew together the older tenets of classical liberalism into a recognisably modern body of classical liberal thinking. Part of his purpose was to show how James II had forfeited his throne by violating the social contract. All sovereignty, he asserted, comes from the people, who submit to it solely in order to boost their security and expand their general freedom. When this contract is broken, individuals have every right to rise up against the sovereign.

Locke also developed natural rights theory, arguing that human beings have inherent rights that exist prior to government and cannot be sacrificed to it. Governments that infringe these rights were illegitimate.

But central to Locke"s ideas was private property, and not just physical property. Locke maintained that people have property in their own lives, bodies and labour - self-ownership. From that crucial understanding, he reasoned that people must also have property in all the things that they had spent personal effort in creating - "mixed their labour" with. The principle of self-ownership therefore makes it cru- cial that such property should be made secure under the law.

These ideas would inform many of the thinkers behind the American Revolution.

The Enlightenment

The eighteenth century saw another revival of classical liber- al thinking. In France, Montesquieu (1689-1755) developed the idea that in a free society and free economy, individuals have to conduct themselves in ways that maintain peaceful cooperation between them - and do so without needing direction from any authority. He therefore called for a system of checks and balances on government power - another idea that would inform American thinkers.

Meanwhile, a growing intellectual revolt against the authoritarianism of the church led to thinkers such as Voltaire (1694-1778) calling for reason and toleration, religious diversity and humane justice. In economics too, intellectuals such as Turgot (1727-81) argued for lifting trade barriers, simplifying taxes and more competitive labour and agricultural markets.

The Scottish philosopher and economist Adam Smith (1723-90) explained, along the lines of Montesquieu, how, in many cases, the free interaction between individuals tended to produce a generally beneficial outcome - an effect dubbed the invisible hand. Self-interest might drive our economic life, but we have to benefit our customers to get any benefit for ourselves.

Smith railed against official monopolies, trade restric- tions, high taxes and the suffocating cronyism between government and business. He believed that open, competi- tive markets would liberate the public, especially the working poor. His ideas greatly influenced policy and ushered in a long period of free trade and economic growth.

The Rechtsstaat

On the European continent, meanwhile, thinkers such as the German philosopher Immanuel Kant (1724-1804) were developing the principles of the "just state" or Rechtsstaat, which would inform the creation of the American and French constitutions in the late eighteenth century.

Kant argued for a written constitution as a way of guaranteeing permanent peaceful co-existence between diverse individuals, which in turn he saw as a basic condition for human happiness and prosperity. He dismissed the Utopian idea that moral education could curb those differences and make everyone"s aims coincide. The state was about enabling diverse individuals to come together for mutual benefit, and the constitution is what held it together.

In the Rechtsstaat, the institutions of civil society - vol- untary associations such as clubs, societies and churches - would have an equal role in promoting this social harmony. Government powers would be restrained by the separation of powers, and judges and politicians would be account- able to and bound by the law. The law itself would have to be transparent, explained and proportionate. The use of force would be strictly limited to the justice system. The test of a government is its maintenance of this just consti- tutional order.

Success and Reassessment

A New Home for Classical Liberalism

Thomas Paine took many of Locke"s classical liberal ideas on natural rights and social contracts, and that govern- ment is a necessary evil that can become intolerable if unchecked. In January 1776 he wove them into his influential call to arms, Common Sense, indicting Britain as being in breach of its contract to the colonists.

It was natural therefore that, after the hostilities, the Americans should seek a new classical liberal contract between themselves and the government they were creating. The Constitution would be infused with Locke"s ideas of natural, inalienable rights, and a Montesquieu-style division of government powers.

The Nineteenth Century

But new and radical classical liberal ideas returned to Britain. By 1833, classical liberal activists had secured the abolition of slavery throughout most of the British Empire, and by 1843 the reform was complete.

Also on the social front, the British philosopher and economist John Stuart Mill (1806-73) articulated the "no harm" principle - that people should be able to act as they please, provided they do not harm others in the process, and thereby diminish their freedom. He also argued for a "personal sphere" that the state could not touch, and, following the utilitarian philosopher Jeremy Bentham (1746- 1832), argued that freedom was the best way to maximise public benefit, or "utility".

In economics, the Anti-Corn-Law League, which sought to end protectionist taxes on imported wheat, grew into the Manchester School, whose leading figures such as Richard Cobden (1804-65) and John Bright (1811-89) called for laissez-faire policies on trade, industry and labour.

Reappraisal and Decline

However, rapid industrialisation after the mid nineteenth century brought challenges for classical liberalism, such as poor working conditions, social stratification, displace- ment and urban poverty. Increasingly, people called on governments to regulate away such ills.

Then in the twentieth century, hostilities and threats in Europe promoted a nationalist culture and greater faith in the role of the state. After each wartime expansion, governments failed to shrink back again. In 1913, before World War II, government expenditure was just 17 per cent of GDP in France, 15 per cent in Germany and 13 per cent in the United Kingdom. It is now roughly three times that as a percentage of GDP, and many times more in absolute terms.

Meanwhile, just as the physical scientists were shaping the physical world, so economists and sociologists fancied that they could shape human society scientifically too. They saw central planning as more rational than the natural disorderliness of markets, with their externalities and their supposed tendency to monopoly or to unemployment. No longer was the onus on interventionists; now the classical liberals were the ones who had to justify their demands to let freedom prevail.

Butler, Eamonn - Classical Liberalism: A Primer - Institute of Economic

Affairs. (2015).

https://iea.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/Butler-interactive.pdf

Classical Liberalism - The Decline

The Decline

In retrospect, we may see the rise of classical liberalism as a thread of individuals and movements revealing both a continuity of ideas and a continual growth, as thinkers refined and added to the basic principles of the thought. The individuals and movements manifested themselves in two major ways. They asserted ideas, as with Locke's defense of property and de Tocqueville's analysis of democracy. Also, they reacted to policies, as with the Scottish Enlightenment and French Physiocratic responses to mercantilism. In both manners of expression, classical liberalism met with some measure of acceptance. Either it was widely read, like Emerson's prose, granted legitimacy through positions of prominence, like Jefferson and Madison's rise to the Presidency, or capable of directing change, like the Manchester School's defeat of the Corn Laws.

Why did classical liberalism achieve this rise? First, the overriding European culture provided those with assertions the opportunity to travel, test their theses against observations, and communicate effectively. Second, the increasingly interdependent nations of Europe could no longer contain their people either economically (protectionism) or politically (absolutism), as the citizens could travel and exchange information concerning conditions elsewhere. For example, England's lead in constitutionalism influenced the classical liberals of the other nations, as did the United States' egalitarianism. Third, some policies such as mercantilism were not successful and thus there was an audience for any alternative, particularly one that worked. A number of combined conditions put Europe in need of economic, political, and philosophical answers, and classical liberalism responded.

By the late 19th century, individuals and movements still asserted classical liberal ideas and reacted to alternative policies. The measure of acceptance was gone, however, although some thinkers were tolerated as dissenters. The West's rapid move toward industrialization created enormous short-term problems of working conditions, poverty or stratification, and displacement. Technological advances raced past the nations' ability to adapt. The people turned to the government, often more democratic in nature than before, to regulate and legislate these transitional hardships away, thus substituting the long-term problem of unprecedented governmental growth for the temporary problems faced until the market adjusted to the new industrial economies.

The experiences of rising hostilities in Europe after the turn of the century replaced the uniting European culture with extreme nationalism and ethnic pride. Not only did World War I destroy international trade, every government expanded to meet military needs. World War II compounded this problem; the United States' government, for example, was now engaged in everything from wage and price controls to rationing, censorship, and propaganda. Once the wars were over, the governments never decreased to their previous sizes. The Soviet embrace of communism, the response of a nation freed from feudalism in the midst of the industrial era without benefit of the European philosophical heritage, kept the nations at a heightened military position while spawning an international flirtation with collectivism. The cultures now accepting of government's ever-broadening role, people expected economic and social needs to be met by legislation. The United States' New Deal and Great Society are indicative of this trend. The states' social involvement and centralized planning made the late 19th and early to mid-20th centuries a regression from freedom, an instance of Spencer's "re-barbarization." I explore those who preserved the message of classical liberalism during this time in the following chronology.

The Austrian School (1871-present)

The movement of longest duration in the classical liberal tradition, the Austrian School...

https://www.belmont.edu/lockesmith/liberalism_essay/the_decline.html

The Rise of the Collectivists

Classical political economy, as taught in the early decades of the 19th century, and in England particularly, did capture the minds of the masses. The advocates of classical liberalism were able to present a vision so compelling, so soulful, that it motivated support for major political reform. Think of the repeal of England’s Corn Laws, surely a difficult step. Why, after all, ought England to give up protection of its farmers? Only by presenting the larger vision of a free‐trade England could the Corn Laws’ opponents prevail with lawmakers. When the reformers succeeded, the repeal’s passage changed the world.

After the middle of the 19th century, however, the soul of the liberal movement lost its way. In 1848 Karl Marx published his Communist Manifesto, and the powerful attractions of socialism made liberalism seem a weak light. From that time onward, classical liberals retreated into a defensive posture, struggling continuously against the reforms promulgated by utilitarian dreamers. Individual liberty was no longer the focus.

The collectivists claimed superior wisdom; life became the pursuit of happiness in the aggregate. Aided and abetted by the Hegel‐inspired political idealists, these new intellectuals shifted away from the notion of personal realization to that of collective psyche. The ideal of socialism was so successful that it led to major political and institutional changes — even when the experience of history showed it to be deeply flawed. What else but the power of the socialist ideal can explain its longevity in Russia or even parts of Western Europe?

https://www.cato.org/policy-report/march/april-2013/saving-soul-classical-liberalism

Psychology Wiki - Classical Liberalism

https://psychology.fandom.com/wiki/Classical_liberalism

How Classical Liberalism Morphed Into New Deal Liberalism - An excerpt from

Eric Alterman's new book, The Cause, attempts to explain the long-asked

question: How did classical liberalism transition into New Deal liberalism?

https://www.americanprogress.org/article/think-again-how-classical-liberalism-morphed-into-new-deal-liberalism/

....................................

https://www.learnliberty.org/blog/what-is-classical-liberalism/

Get code for 4 videos - 3 part on classical liberalism and one by

Picketty

https://bigthink.com/thinking/classical-liberalism-explained/

Accepting the theory of America as essentially a liberal society, how can one distinguish the liberal and conservative tendencies within that society? https://writing.upenn.edu/~afilreis/50s/schleslib.html

Classical Liberalism vs. Modern Liberalism

What's the best way to secure everyone's mastery over his or her own

destiny?

https://reason.com/2012/08/12/classical-liberalism-vs-modern-liberalis/