Transcript

00:15 - You all know the truth of what I'm going to say. I think the intuition that inequality is divisive and socially corrosive has been around since before the French Revolution. What's changed is we now can look at the evidence, we can compare societies, more and less equal societies, and see what inequality does. I'm going to take you through that data and then explain why the links I'm going to be showing you exist.

00:45 - But first, see what a miserable lot we are. (Laughter) I want to start though with a paradox. This shows you life expectancy against gross national income -- how rich countries are on average. And you see the countries on the right, like Norway and the USA, are twice as rich as Israel, Greece, Portugal on the left. And it makes no difference to their life expectancy at all. There's no suggestion of a relationship there. But if we look within our societies, there are extraordinary social gradients in health running right across society. This, again, is life expectancy.

01:26 - These are small areas of England and Wales -- the poorest on the right, the richest on the left. A lot of difference between the poor and the rest of us. Even the people just below the top have less good health than the people at the top. So income means something very important within our societies, and nothing between them. The explanation of that paradox is that, within our societies, we're looking at relative income or social position, social status -- where we are in relation to each other and the size of the gaps between us. And as soon as you've got that idea, you should immediately wonder: what happens if we widen the differences, or compress them, make the income differences bigger or smaller?

02:15 - And that's what I'm going to show you. I'm not using any hypothetical data. I'm taking data from the U.N. -- it's the same as the World Bank has -- on the scale of income differences in these rich developed market democracies. The measure we've used, because it's easy to understand and you can download it, is how much richer the top 20 percent than the bottom 20 percent in each country. And you see in the more equal countries on the left -- Japan, Finland, Norway, Sweden -- the top 20 percent are about three and a half, four times as rich as the bottom 20 percent. But on the more unequal end -- U.K., Portugal, USA, Singapore -- the differences are twice as big. On that measure, we are twice as unequal as some of the other successful market democracies.

02:62 - Now I'm going to show you what that does to our societies. We collected data on problems with social gradients, the kind of problems that are more common at the bottom of the social ladder. Internationally comparable data on life expectancy, on kids' maths and literacy scores, on infant mortality rates, homicide rates, proportion of the population in prison, teenage birthrates, levels of trust, obesity, mental illness -- which in standard diagnostic classification includes drug and alcohol addiction -- and social mobility. We put them all in one index. They're all weighted equally. Where a country is is a sort of average score on these things. And there, you see it in relation to the measure of inequality I've just shown you, which I shall use over and over again in the data. The more unequal countries are doing worse on all these kinds of social problems. It's an extraordinarily close correlation. But if you look at that same index of health and social problems in relation to GNP per capita, gross national income, there's nothing there, no correlation anymore.

04:14 - We were a little bit worried that people might think we'd been choosing problems to suit our argument and just manufactured this evidence, so we also did a paper in the British Medical Journal on the UNICEF index of child well-being. It has 40 different components put together by other people. It contains whether kids can talk to their parents, whether they have books at home, what immunization rates are like, whether there's bullying at school. Everything goes into it. Here it is in relation to that same measure of inequality. Kids do worse in the more unequal societies. Highly significant relationship. But once again, if you look at that measure of child well-being, in relation to national income per person, there's no relationship, no suggestion of a relationship.

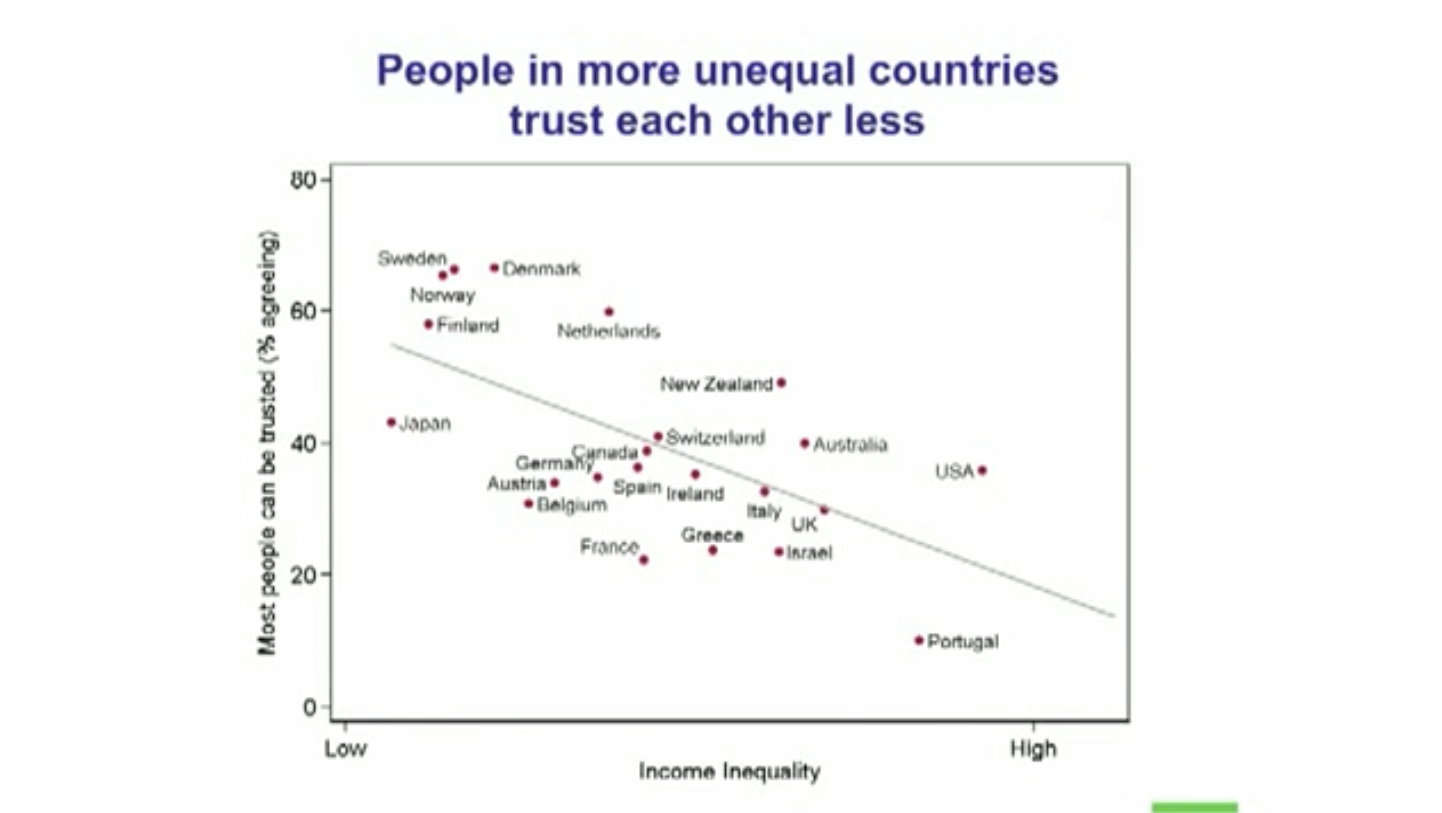

04:66 - What all the data I've shown you so far says is the same thing. The average well-being of our societies is not dependent any longer on national income and economic growth. That's very important in poorer countries, but not in the rich developed world. But the differences between us and where we are in relation to each other now matter very much. I'm going to show you some of the separate bits of our index. Here, for instance, is trust. It's simply the proportion of the population who agree most people can be trusted. It comes from the World Values Survey. You see, at the more unequal end, it's about 15 percent of the population who feel they can trust others. But in the more equal societies, it rises to 60 or 65 percent. And if you look at measures of involvement in community life or social capital, very similar relationships closely related to inequality.

05:65 - I may say, we did all this work twice. We did it first on these rich, developed countries, and then as a separate test bed, we repeated it all on the 50 American states -- asking just the same question: do the more unequal states do worse on all these kinds of measures? So here is trust from a general social survey of the federal government related to inequality. Very similar scatter over a similar range of levels of trust. Same thing is going on. Basically we found that almost anything that's related to trust internationally is related to trust amongst the 50 states in that separate test bed. We're not just talking about a fluke.

06:45 - This is mental illness. WHO put together figures using the same diagnostic interviews on random samples of the population to allow us to compare rates of mental illness in each society. This is the percent of the population with any mental illness in the preceding year. And it goes from about eight percent up to three times that -- whole societies with three times the level of mental illness of others. And again, closely related to inequality.

07:17 - This is violence. These red dots are American states, and the blue triangles are Canadian provinces. But look at the scale of the differences. It goes from 15 homicides per million up to 150. This is the proportion of the population in prison. There's a about a tenfold difference there, log scale up the side. But it goes from about 40 to 400 people in prison. That relationship is not mainly driven by more crime. In some places, that's part of it. But most of it is about more punitive sentencing, harsher sentencing. And the more unequal societies are more likely also to retain the death penalty. Here we have children dropping out of high school. Again, quite big differences. Extraordinarily damaging, if you're talking about using the talents of the population.

08:16 - This is social mobility. It's actually a measure of mobility based on income. Basically, it's asking: do rich fathers have rich sons and poor fathers have poor sons, or is there no relationship between the two? And at the more unequal end, fathers' income is much more important -- in the U.K., USA. And in Scandinavian countries, fathers' income is much less important. There's more social mobility. And as we like to say -- and I know there are a lot of Americans in the audience here -- if Americans want to live the American dream, they should go to Denmark.

08:57 - (Laughter)

08:59 - (Applause)

08:63 - I've shown you just a few things in italics here. I could have shown a number of other problems. They're all problems that tend to be more common at the bottom of the social gradient. But there are endless problems with social gradients that are worse in more unequal countries -- not just a little bit worse, but anything from twice as common to 10 times as common. Think of the expense, the human cost of that.

09:29 - I want to go back though to this graph that I showed you earlier where we put it all together to make two points. One is that, in graph after graph, we find the countries that do worse, whatever the outcome, seem to be the more unequal ones, and the ones that do well seem to be the Nordic countries and Japan. So what we're looking at is general social disfunction related to inequality. It's not just one or two things that go wrong, it's most things.

09:58 - The other really important point I want to make on this graph is that, if you look at the bottom, Sweden and Japan, they're very different countries in all sorts of ways. The position of women, how closely they keep to the nuclear family, are on opposite ends of the poles in terms of the rich developed world. But another really important difference is how they get their greater equality. Sweden has huge differences in earnings, and it narrows the gap through taxation, general welfare state, generous benefits and so on. Japan is rather different though. It starts off with much smaller differences in earnings before tax. It has lower taxes. It has a smaller welfare state. And in our analysis of the American states, we find rather the same contrast. There are some states that do well through redistribution, some states that do well because they have smaller income differences before tax. So we conclude that it doesn't much matter how you get your greater equality, as long as you get there somehow.

10:60 - I am not talking about perfect equality, I'm talking about what exists in rich developed market democracies. Another really surprising part of this picture is that it's not just the poor who are affected by inequality. There seems to be some truth in John Donne's "No man is an island." And in a number of studies, it's possible to compare how people do in more and less equal countries at each level in the social hierarchy. This is just one example. It's infant mortality. Some Swedes very kindly classified a lot of their infant deaths according to the British register of general socioeconomic classification. And so it's anachronistically a classification by fathers' occupations, so single parents go on their own. But then where it says "low social class," that's unskilled manual occupations. It goes through towards the skilled manual occupations in the middle, then the junior non-manual, going up high to the professional occupations -- doctors, lawyers, directors of larger companies.

11:71 - You see there that Sweden does better than Britain all the way across the social hierarchy. The biggest differences are at the bottom of society. But even at the top, there seems to be a small benefit to being in a more equal society. We show that on about five different sets of data covering educational outcomes and health in the United States and internationally. And that seems to be the general picture -- that greater equality makes most difference at the bottom, but has some benefits even at the top.

12:44 - But I should say a few words about what's going on. I think I'm looking and talking about the psychosocial effects of inequality. More to do with feelings of superiority and inferiority, of being valued and devalued, respected and disrespected. And of course, those feelings of the status competition that comes out of that drives the consumerism in our society. It also leads to status insecurity. We worry more about how we're judged and seen by others, whether we're regarded as attractive, clever, all that kind of thing. The social-evaluative judgments increase, the fear of those social-evaluative judgments.

13:29 - Interestingly, some parallel work going on in social psychology: some people reviewed 208 different studies in which volunteers had been invited into a psychological laboratory and had their stress hormones, their responses to doing stressful tasks, measured. And in the review, what they were interested in seeing is what kind of stresses most reliably raise levels of cortisol, the central stress hormone. And the conclusion was it was tasks that included social-evaluative threat -- threats to self-esteem or social status in which others can negatively judge your performance. Those kind of stresses have a very particular effect on the physiology of stress.

14:20 - Now we have been criticized. Of course, there are people who dislike this stuff and people who find it very surprising. I should tell you though that when people criticize us for picking and choosing data, we never pick and choose data. We have an absolute rule that if our data source has data for one of the countries we're looking at, it goes into the analysis. Our data source decides whether it's reliable data, we don't. Otherwise that would introduce bias.

14:50 - What about other countries? There are 200 studies of health in relation to income and equality in the academic peer-reviewed journals. This isn't confined to these countries here, hiding a very simple demonstration. The same countries, the same measure of inequality, one problem after another. Why don't we control for other factors? Well we've shown you that GNP per capita doesn't make any difference. And of course, others using more sophisticated methods in the literature have controlled for poverty and education and so on.

15:30 - What about causality? Correlation in itself doesn't prove causality. We spend a good bit of time. And indeed, people know the causal links quite well in some of these outcomes. The big change in our understanding of drivers of chronic health in the rich developed world is how important chronic stress from social sources is affecting the immune system, the cardiovascular system. Or for instance, the reason why violence becomes more common in more unequal societies is because people are sensitive to being looked down on.

15:66 - I should say that to deal with this, we've got to deal with the post-tax things and the pre-tax things. We've got to constrain income, the bonus culture incomes at the top. I think we must make our bosses accountable to their employees in any way we can. I think the take-home message though is that we can improve the real quality of human life by reducing the differences in incomes between us. Suddenly we have a handle on the psychosocial well-being of whole societies, and that's exciting.

16:40 - Thank you.

16:42 - (Applause)

https://www.ted.com/talks/richard_wilkinson_how_economic_inequality_harms_societies/

There are pernicious effects that inequality has on societies: eroding trust, increasing anxiety and illness, (and) encouraging excessive consumption.

For Each of 11 Different Health and Social Problems:

- Physical Health

- Mental Health

- Drug Abuse

- Education

- Imprisonment

- Obesity

- Social Mobility

- Trust & Community Life

- Violence

- Teenage Pregnancies,

- Child Well-being,

Outcomes are significantly worse in more unequal rich countries.

The Spirit Level - Why Greater Equality Makes Societies Stronger

The path-breaking book, ‘The Spirit Level’ showed how gross inequalities damage the whole of society. For all the developed capitalist countries without exception, the international measure of inequality, the Gini coefficient, showed a continuous decline in inequality in incomes from 1945 to the late 1970s. From then on there developed a marked disparity between the continental European countries, where the trend continued, and the Anglo-Saxon economies, where it went into sharp reverse, continuing up to the present.

Academic and political criticism of this trend towards greater inequality has until recently concentrated on its manifest injustice, underpinned by theories of justice elaborated within disciplines such as political philosophy. The importance of The Spirit Level, by Richard Wilkinson and Kate Pickett, lies in showing that increased levels of inequality lead to an intensification of a whole range of social ills which affect everyone in society. By comparing the evidence from 25 advanced countries and the 50 US states, which all differ markedly in their levels of inequality, the authors demonstrate through a series of tables that all the main social ills correlate closely with high inequality, devoting a chapter to each:

- low levels of social trust

- mental illness (including drug and alcohol addiction)

- lower life expectancy and higher infant mortality

- obesity

- poor educational performance

- teenage births

- homicides

- imprisonment rates

- reduced social mobility

What is the causal link at work?

One obvious cause is that in highly unequal societies there are more people living in poverty and deprived conditions, and exposed to their effects. However, the key finding is that the ill effects extend throughout the social scale in unequal societies, directly as well as indirectly. “Income inequality exerts a comparable effect across all population subgroups…like a pollutant spread throughout society”. This is because of the marked status distinctions that follow from economic inequality, and the effect these have on the quality of social relationships and people’s sense of self-worth throughout the social scale. In a previous book, Wilkinson summarised the causal chain as follows:

Greater income inequality < increased social distance between groups, less sense of common identity < more dominance and subordination, hierarchical and authoritarian values < increased status competition, emphasis on self-interest and material success < others as rivals, poorer quality of social relations.

In terms of the effect on health, he showed from studies of Whitehall civil servants that those lower down the office hierarchy suffered more from cardio-vascular disease, and that this was due to the effect of stressful lack of control over work on the chemistry of the body (repeated in the present book). This condition of lack of control, status anxiety and fragmented social relations lies at the root of all the social ills documented in the latest book, and can be traced to the same cause of income inequality.

It is the experience of low status and low esteem that encourages violence, obesity, teenage pregnancy, drug use, and so on; and it is the fear of it that drives consumerism, longer working hours and other economic dysfunctionalities of unequal societies. In sum, “the role of this book is to point out that greater equality is the material foundation on which better social relations are built.”

What are the policy implications?

The implications of the work are that three types of ameliorative policy are mistaken if not actually futile:

- Treating each of the social ills separately involves dealing with the symptoms, not the underlying cause that connects them all, and involves high levels of public expenditure which would be better spent on reducing the inequalities in the first place.

- Poverty alleviation strategies on their own, which aim to lift the lowest, do not touch the structural consequences of inequality, which remain in place. Huge salaries at the top are particularly dysfunctional, as their influence permeates throughout the social and occupational hierarchy.

- The socio-psychological effects of inequality on individuals can only at best be ameliorated by cognitive behaviour therapy and such-like (as per Richard Layard’s Happiness), since the condition is set to be continually reproduced if the underlying inequality is not addressed.

What should be done and by whom?

In the final chapters of the book the authors set out a mixed agenda of proposals, which all assume that the inequalities of the dysfunctional societies are not a natural phenomenon, but socially and politically constructed, and therefore open to change, as evidenced by the example of more equal societies (Japan and the Nordic countries). These countries are all “market democracies”, so the changes are not insuperable, though they will take “many decades”. The problem of climate change, they point out, requires movement in the same direction. Among their proposals are:

- The establishment of a wide social and political movement for greater equality, working through all civil society organisations. The key for such a movement is “to map out ways in which the new society can begin to grow within and alongside the institutions it may gradually marginalise and replace….Rather than simply waiting for government to do it for us, we have to start making it in our lives and in the institutions of our society straight away”. In support of such a movement, the evidence of the book turns what previously were purely private beliefs in equality “into publicly demonstrable facts”;

- Among the key institutions of this new society will be employee-owned and managed businesses, using participative methods of organisation which break with the hierarchical principles of the unequal society;

- Of course there is an important role for government. It was the governments of the Thatcher and Reagan era that set the Anglo-Saxon countries on the road to greater inequality, and this can be reversed with wide-ranging policies, but they will take a long time to have effect;

- The wealthy should not be allowed to stand in the way. “We should not allow ourselves to believe that the rich are scarce and precious members of a superior race of more intelligent beings on whom the rest of us are dependent. That is merely the illusion that wealth and power create”.

What is likely to be done?

Wilkinson and Pickett’s book provoked considerable discussion and concern when it was first published a year ago, but its message has now almost totally disappeared from public view. Nothing is more indicative of the diminished political discourse in the UK than the fact that, with a general election only weeks away, the issue of the gross inequalities of our society is virtually absent from the agenda of the main political parties.

The reasons are not far to seek. These parties all continue to subscribe to the neo-liberal economic ideology which has brought us economic collapse on top of the inequalities documented by the book; they wish nothing more than a return to “business as usual”. The rich and powerful continue to exercise a stranglehold over the popular media and public policy alike. And there is something deep-seated in the Anglo-Saxon mentality which needs to have lesser breeds to demonise, whether they be unmarried or teenage parents, childhood offenders, the overweight, or whoever, and to subject them to punitive policies.

In the absence of a serious public debate about the message of this book, we shall continue to apply sticking plaster to the multiple social ills it documents, and at enormous cost to taxpayers as well as to the quality of the society.

David Beetham is a leading political theorist and author of numerous books. He has made a major contribution to assessing the quality of democracy throughout the world with his work with Democratic Audit in the UK, International IDEA (The International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance) and the Inter-Parliamentary Union.

Book review: The Spirit Level | openDemocracy

https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/opendemocracyuk/book-review-spirit-level/

The Inner Level - How More Equal Societies Reduce Stress, Restore Sanity and Improve Everyone's Well-Being

A follow up to the 2009 book The Spirit Level, The Inner Level argues that inequality worsens many social problems including mental and physical health, levels of child well-being, violence, the number of people in prison, drug and alcohol addiction. The book uses extensive comparative psychological data and research from around the globe to set out a convincing argument that the more unequal the society, the higher the ratesof individual and societal distress.

Within this model, competition for power leads to a set of dominance and subordination behaviours, centring on pride and shame. The book illustrates many studies which show that in more unequal societies, this competitive distrust causes withdrawal from community life resulting in a range of mental and physical health issues, and anti-social behaviours.

'The Inner Level' (Wilkinson and Pickett) - a review

https://wbg.org.uk/blog/the-inner-level-wilkinson-and-pickett-a-review/

The Divide is a UK/US documentary film directed by British film-maker Katharine Round. It was produced by Katharine Round and Christopher Hird. It is an adaptation of the acclaimed 2009 socio-economic book The Spirit Level by Richard G. Wilkinson and Kate Pickett The book argues that there are "pernicious effects that inequality has on societies: eroding trust, increasing anxiety and illness, (and) encouraging excessive consumption".

The Whitehall Studies - How Inequality Destroys Psychology & Health:

Both studies found that - there was a significant gradient to morbidity & mortality from heart disease between all levels of the civil service hierarchy - This difference—which in the first study meant that the lowliest employees suffered three times the rate of heart disease for those at the top—was only partially explained by known risk factors, such as diet, exercise and smoking."

Clip Above From The Documentary - Stress, Portrait of a Killer

- https://youtu.be/eYG0ZuTv5rs

The name 'Whitehall' originates from the first Whitehall study of 18,000 men in the Civil Service, set up in 1967. The first Whitehall study showed that men in the lowest employment grades were much more likely to die prematurely than men in the highest grades. The Whitehall II study was set up to determine what underlies this grade or social gradient in death and disease and to include women.

https://sheffieldequality.files.wordpress.com/2012/11/the-whitehall-studies.pdf( https://www.sheffield.gov.uk/home/your-city-council/our-equality-duty )

The Broken Ladder - How Inequality Affects The Way We Think, Live & Die

Research in psychology, neuroscience, and behavioral economics has not only revealed important new insights into how inequality changes people in predictable ways but also provided a corrective to the flawed view of poverty as being the result of individual character failings. Among modern developed societies, inequality is not primarily a matter of the actual amount of money people have. It is, rather, people's sense of where they stand in relation to others. Feeling poor matters--not just being poor. Regardless of their average incomes, countries or states with greater levels of income inequality have much higher rates of all the social maladies we associate with poverty, including lower than average life expectancies, serious health problems, mental illness, and crime.

The Broken Ladder explores such issues as why women in poor societies often have more children, and why they have them at a younger age; why there is little trust among the working class in the prudence of investing for the future; why people's perception of their social status affects their political beliefs and leads to greater political divisions; how poverty raises stress levels as effectively as actual physical threats; how inequality in the workplace affects performance; and why unequal societies tend to become more religious. Understanding how inequality shapes our world can help us better understand what drives ideological divides, why high inequality makes the middle class feel left behind, and how to disconnect from the endless treadmill of social comparison.

https://immortalista.blogspot.com/p/broken-ladder-by-keith-payne.html

For 97% of Human History Equality Was The Norm. What Happened?

…Somehow, after 290,000 years of living without anyone having the power to tell us what to do, and with every member of a community having about as much as everyone else, most of us are now subject to command, and with immensely less than a favoured few. Why? Of course, in the state societies we live in, there’s no mystery about the many accepting their subordination to elites. While elites are vastly outnumbered, they control the army, the police, the state apparatus. An attempt to seize elite wealth would be met by overwhelming coercive power, and even successful revolutions have a dismal record of largely replacing one elite with another, usually at the expense of many lives, mostly of the poor. So, for those outside the elite world, their least-worst option is to accept subordination, perhaps with individual or collective attempts at amelioration, depending on the specifics of the political environment.

No social world ever went from an egalitarian community to an elite-dominated, state-structured society in one fell swoop. It’s a gradual movement towards inequality. The pathway to inequality leads through unequal, but still small-scale and stateless, communities, in which incipient elites lived with and among their neighbours, and without control of coercive state institutions. As such, they were vulnerable, and as Christopher Boehm notes in Hierarchy in the Forest (1999), and Stephen Pinker too, in The Better Angels of Our Nature (2011), the denizens of pre-state communities aren’t shy about the judicious application of violence. So how did inequality establish and grow without the cloak of law and the shield of organised state power?

Once hereditary leadership backed by military power establishes, subordination and inequality are explained by entrenched differences in access to force. So the critical problem is to explain inequality in village societies where it doesn’t yet have the protection of institutionalised power. These ‘transegalitarian communities’ are dominated by ‘Big Men’ (as they’re called in New Guinea and Melanesia), that is, individuals with wealth and status. But they don’t rule as a right, and their sons don’t automatically inherit their standing. It’s in communities of this kind that inequality establishes. Once these cultures exist, we’ve had a shift from social worlds that were equal to worlds in which inequality was a routine and accepted fact of life – so much so that it often seemed natural.

There are two developments in mobile forager cultures that tend to set the stage for the establishment of inequality. One such scaffold to inequality was the emergence of clan structure. Clans have a strong corporate identity, built around real or mythical genealogical connection, reinforced by demanding initiation rites and intense collective activities. They become central to an individual’s social identity. Individuals see themselves, and are seen by others, primarily through their clan identity. They expect and get social support mostly within their clan, as the anthropologist Raymond C Kelly writes in Warless Societies and the Origin of War (2000). Once storage and farming emerged, incipient elites used clan membership to mobilise social and material support.

The second development was the emergence of a quasi-elite based on the control of information, which created a hierarchy of prestige and esteem, rather than wealth and power. This was originally based on subsistence skills. Forager life depends on very high levels of expertise in navigation, tracking, plant identification, animal behaviour, and artisan skills. The genuinely expert attract deference and respect in return for generously sharing their knowledge, as the evolutionary biologist Joseph Henrich argues in The Secret of Our Success (2015). As the social anthropologist Jerome Lewis has shown, this economy of information can include story and music, and the same can be true of its ritual and normative life. Indeed, there might be a fusion of ritual with subsistence information, if ritual narratives are used as a vehicle for encoding important but rarely used spatial and navigational information. There’s some suggestion of this fusion in Australian Aboriginal songlines, and the idea is expanded from Australia and defended in detail by the orality scholar Lynne Kelly in Knowledge and Power in Prehistoric Societies (2015). So there can be expertise and deference not just in subsistence skills, but also with regards to religion and ritual.

Farming and storage make inequality possible, even likely, because they tend to undermine sharing norms...

https://aeon.co/essays/for-97-of-human-history-equality-was-the-norm-what-happened

The Creation of Inequality - How Our Prehistoric Ancestors Set the Stage for Monarchy, Slavery, and Empire - Kent Flannery, Joyce Marcus

of every human group.

A few societies allowed talented and ambitious individuals to rise in prestige while still preventing them from becoming a hereditary elite. But many others made high rank hereditary, by manipulating debts, genealogies, and sacred lore. At certain moments in history, intense competition among leaders of high rank gave rise to despotic kingdoms and empires in the Near East, Egypt, Africa, Mexico, Peru, and the Pacific.

Drawing on their vast knowledge of both living and prehistoric social groups, Flannery and Marcus describe the changes in logic that create larger and more hierarchical societies, and they argue persuasively that many kinds of inequality can be overcome by reversing these changes, rather than by violence.

https://www.hup.harvard.edu/catalog.php?isbn=9780674416772

Review of The Creation of Inequality - How Our Prehistoric Ancestors Set the Stage for Monarchy, Slavery, and Empire.

It weaves together salient pieces of the anthropological and ar- chaeological record to take its readers on an edifying journey from Sumer to Samoa—and many places in between—to meet humanity’s dramatis personae in the 15,000 year epic of social inequality.

Fittingly, the authors begin and conclude their story in dialogue with Rousseau, whose famous 1753 treatise specu- lated that the end of human equality arrived with the unfor- tunate transition out of some idealized pre-society, Arcadia. Their approach, which marries archaeological evidence with anthropological interpretation reveals a complex and uneven development—there is no “state of nature” here.

At a hulking 648 pages, The Creation of Inequality is orga- nized in 24 chapters that move more or less progressively from history’s relatively egalitarian hunter-gatherer groups, such as the Caribou and Netsilik Eskimos and the !Kung of southern Africa, to the multi-level administrative empires of the Aztec and Inca. Along the way, Flannery and Marcus dedicate lengthy sections to discussion of the various “clues” which reveal how the “social logic” of more equal societies, manifested in prac- tices such as meat-sharing partnerships, gift-exchange, and prestige-based, non-hereditary leadership (i.e., Melanesian “big men”), gave way to the logic of inequality in societies with—among other things—taxes, bureaucracies, separate burial practices for nobles and commoners, and, importantly, hereditary formal power. Key to their analysis is their con- ception of the unique role of the “sacred” in human societies. Looking to chimps, who compete and assemble themselves hierarchically into alphas, betas and gammas, Flannery and Marcus observe that even outwardly egalitarian hunter-gath- erers preserve hierarchy by making their supernatural beings the alphas, their ancestors the betas, and themselves the un- differentiated gammas. Moving toward institutionalized social inequality has thus often involved certain gammas’ claiming power legitimated by special—and often hereditary—relation- ships to these sacred alphas and betas. Clearly, European kings were not the only ones who invoked the divine right to rule…

https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3839&context=jssw

The Creation of Inequality - Reviewed by Eric Poehler

The authors ask this, as Rousseau did, in words that permeate and frame the book: “Man is born free, and yet we see him everywhere in chains” (v, 563). This volume is about addressing that fact and answering why we let it happen.

Part 1 of The Creation of Inequality takes the reader though Rousseau’s “state of Nature” and sets the baseline in the Paleolithic for the development of inequality. Physical differences had always separated members of species—strength, agility, intelligence—and they form the basis of social organization in our nearest primate kin. Thus, in chimpanzee troupes, the strongest (the alphas) dominate the rest through violence, betas dominate all but the alphas, and so on. The authors compare this “natural” order to the stratification of beings in early cosmologies: gods are all-powerful alphas, ancestors are betas, and humans can only be gammas. What separated humans from chimpanzees and prevented our earliest societies from being ruled by force was our capacity for language. In these first chapters, Flannery and Marcus demonstrate how most early groups used shame, humor, and the clamor of the group to maintain fairness among its members.

Yet the authors argue that while the original social experimenters who first invented groups larger than the extended family (i.e., clans) were solving internal inequality, they were also creating new external forms of exclusion: an “us-versus-them” mentality and a concept of “social substitutability” (40). In these pages are the fascinating first steps toward blood feuds, spiraling through alliances and escalating into warfare. Embedded within these actions are the people who will take up leadership positions, profit from them, and attempt to make their positions hereditary.

The second and third parts of the book explore the multiplicity of ways that achieved-rank leaders attain that power, how they manifest it, and how they at times have attempted to pass it on. Part 2 begins by discussing the invention of agriculture and its social effects. The authors reject the determinism of grand theories of the Neolithic Revolution and instead make good use of particular urban spaces, examining their articulation as a means to materialize social order and to document the changes to that order. Specifically, men’s ritual houses are studied across cultures and across millennia to show the shift from private rituals to more public performances, leading to the quintessential form of monumental public architecture: the temple. These threads culminate in the capital cities of Laphta (Tonga) and La Venta (Mexico), where the competitive building of ancestor mounds and monoliths produced vast and rich sacro-urban landscapes as visual justification for the formal, hierarchical stratification of society.

In the remainder of the book, the authors address the development of kingdoms and their metastasizing into empires. The Hawaiian Islands, where the rich ethnographic and archaeological evidence illustrates the intense and extended competition among hereditary chiefs, generation after generation, set the stage for other famous, first-generation states to be explored: Zulu, Zapotec, Egypt, Uruk. What the Hawaiian example does best is to convey simultaneously the shocking speed with which a state appears to form (including attendant cosmological changes) and the long, messy processes of its adolescence (347). If states are made in the subjugation or annexation of chiefdoms, then empires are made by states swallowing other states. When seen historically as, respectively, a fifth-generation state and second-generation empire, a reconsideration of the traditional histories of the Aztec and Inka is fascinating. Flannery and Marcus persuasively show how states breed new states out of necessity (e.g., threatened chiefdoms join together to fight back against aggressive states), and, once the seeds of this new social organization are sown, how new states can use this new social strategy not only to resist but also to usurp their attackers en route to empire...

https://www.ajaonline.org/book-review/1659

From Cattle to Capital - How Agriculture Bred Inequality

The gap between rich and poor is one of the great concerns of modern times. It's even driving archaeologists to look more closely at wealth disparities in ancient societies.

"That's what's so fun about it," says Timothy Kohler, at Washington State University. "It widens our perspective, and allows us to see that the way things are organized now is not the only way for things to be organized."

Measuring inequality in societies that didn't leave written records is hard, of course. But physical ruins remain, and Kohler figured that even long ago, the richer you were, the bigger the house you probably occupied.

So he and his colleagues collected measurements of homes from many different early human societies, including nomadic groups that depended on hunting, others that relied on small-scale growing of food, and early Roman cities. There were 63 sites in all, ranging in age from 9000 B.C. to 1500 A.D.

In a report that appears this week in the journal Nature, Kohler reports that increasing inequality arrived with agriculture. When people started growing more crops, settling down and building cities, the rich usually got much richer, compared to the poor.

That's what most anthropologists expected, but there were interesting exceptions to the rule. Inequality was not inevitable. The civilization of Teotihuacan, which flourished in present-day Mexico almost a thousand years ago, was based on large-scale agriculture, yet "had remarkably low wealth disparities," Kohler says.

Kohler's data also showed something completely unexpected. After the advent of agriculture, "for some reason, wealth gets much more unequally distributed in the Old World, Europe and Asia, than it does in the New World," Kohler says. "This was a total surprise."

Kohler isn't sure why this happened, but he has some ideas. "Think about it," he says. "You know that animals like cows, oxen, horses, sheep, goats, pigs, all are Old World domesticates." Through an accident of geography and evolution, they simply didn't exist in the Americas before Columbus arrived.

So it was only in the Old World that ancient farmers could use oxen to plow more fields, expand production, and get richer, compared to poorer farmers who could not afford those animals.

They were accumulating wealth, what economists call capital — a term that Kohler says is no accident. "Our word 'capital' comes from the same proto- Indo-European root as our word for 'cattle' does," he says.

There's debate about whether this ancient history is relevant to current debates. But archaeologist Michelle Elliott, who teaches at the Sorbonne-Pantheon university in Paris, says a lot of archaeologists believe it is. "They feel like, 'We have all these data about our species, that go back to its origins,' " she says, and it would be nice if those data could somehow help solve problems today.

Elliot, who wrote a commentary on Kohler's research for Nature, says that Kohler's research is based on a relatively small sample of sites, and she's hoping that archaeologists will analyze data from additional ancient civilizations, to see if they also fit that pattern that Kohler observed.

From Cattle to Capital: How Agriculture Bred Inequality

(same article) New Study Charts Inequality Across Millennia

https://santafe.edu/news-center/news/new-study-charts-inequality-across-millennia

Demonetization - In the Kodak years, photography was expensive. You paid for the camera, for the film, for developing the film, and so on. Today, during the Megapixel era, the camera is free in your phone, no film, no developing. Completely demonetized.

http://www.21stcentech.com/demonetizing-living-costs-peter-diamandis-talks-technological-socialism/

Inequality and Violence An historian sees death and destruction as the only effective levelers.

The Great Leveler: Violence and the History of Inequality, by Stanford University historian Walter Scheidel. He argues that war, revolution, state collapse, and plague may be about the only things that have ever substantially reduced inequality of wealth and income in the five thousand years since people started forming agrarian civilizations and living under kingdoms, empires, and states. His research finds that inequality has always made a rapid comeback once the catastrophes that leveled it had receded. Inequality effectively dropped in the U.S. and other western countries in the wake of the Great Depression and two world wars, he notes, but its return to high levels during the past two decades confirms his general premise. Is this pattern telling us anything about human nature or psychology?

The surprising factors driving murder rates: income inequality and respect

https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2017/dec/08/income-inequality-murder-homicide-rates

Homicide rates are lower and children experience less violence in more equal societies.

https://www.equalitytrust.org.uk/violence

Disease, violence and inequality threaten more adolescents worldwide than ever before

https://www.eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2019-03/tl-pss031119.php

Income Inequality’s Most Disturbing Side Effect: Homicide

https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/income-inequalitys-most-disturbing-side-effect-homicide/

Inequality may lead to violence and extremism

http://sciencenordic.com/inequality-may-lead-violence-and-extremism

Violent disorder is on the rise. Is inequality to blame?

https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2019/01/violent-disorder-is-on-the-rise-is-inequality-to-blame/

“It has been proven, less inequality means less crime”

The injustice of inequality and its links to violence

https://www.kpsrl.org/blog/the-injustice-of-inequality-and-its-links-to-violence

Does Inequality Cause Crime? New research suggests that what matters isn't disparity itself, but whether people are flaunting their riches.

https://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2014/10/does-inequality-cause-crime/381748/

Violent crime is like infectious disease – and we know how to stop it spreading

Economist Thomas Piketty, who specializes in the study of economic inequality, argues that widening economic disparity is an inevitable phenomenon of free market capitalism when the rate of return of capital (r) is greater than the rate of growth of the economy (g).

...When the rate of return on capital exceeds the rate of growth of output and income, as it did in the nineteenth century and seems quite likely to do again in the twenty-first, capitalism automatically generates arbitrary and unsustainable inequalities that radically undermine the meritocratic values on which democratic societies are based...

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Economic_inequality

Why We Cant Afford The Rich - unearned income’, ‘rentiers’, ‘functionless investors’

...In this article Andrew Sayer revives some concepts – ‘unearned income’, ‘rentiers’, ‘functionless investors’, and ‘improperty’ – to explain why the very rich are unjust and dysfunctional. We need to challenge the myth that the rich are specially-talented wealth creators, he argues...

...The early sections of the book set out Sayer’s most interesting arguments: namely, that the wealth of the rich is unearned, and thus amounts to the extraction of value created by others or else simply speculation. His approach is an updated version of Marxist economic thought and differs fundamentally from the starting assumptions of mainstream economics.

For Sayer, economics is about ‘provisioning’: ‘how societies provide themselves with the wherewithal to live’ (20). This involves the production of food and commodities as well as caring for and educating others, and can take place within the market as well as outside of it. From this perspective there is a difference between the usefulness of goods or services (use value) and their market price (exchange value). There is a difference between performing labour that genuinely improves people’s lives and the unproductive income generated from monopolising a scarce resource. Thus, income that comes from work which produces use value is earned, and income that is either produced without working or by work which does not produce use value is unearned.

Sayer spends the (first) half of the book establishing his claim that the rich owe the majority of their wealth to unearned income. This happens in a number of different ways. Firstly, the rich derive a significant part of their wealth from their ability to monopolise scarce resources. The most important of these is land, with many of the very rich owing their affluence to huge investments in the property market. Wealth derived from such sources is unproductive because it does not create use value: it is simply an arrangement of property rights which allows some to profit from their ownership of scarce assets. Similarly, hedge funds or investment banks in which the very wealthy invest their money often speculate on commodity prices or use financial products such as derivatives, which are essentially methods of ‘value-skimming’.

Sayer discusses a (second) source of unearned income for the rich under the heading of ‘usury’. The economic institution of interest rates, and especially compound interest, interacts with existing distributions of wealth to essentially redistribute wealth to the already well off. In Britain only those in the top one per cent of income distribution make more in interest on their savings than they pay out in interest on debts (69). Sayer sees wealth from lending money when high rates of interest are charged as fundamentally unearned, because the rich are simply taking advantage of an unequal power relationship between themselves and the less well off.

(Thirdly), the income of the rich is unearned even if they invest in corporations which create useful goods or services because they are profiting from the labour of the people who actually do the work. Sayer argues that share portfolios are too diversified and change too frequently for shareholders to have any positive role in running the companies they own: they are typically simply speculating on movements in share prices. As a result, the majority of the income that shareholders receive is simply the result of property relations that allow them to extract the earned income of workers.

...the specific institutions of contemporary ‘neo-liberal’ capitalism generate unjust and socially damaging inequalities. In sum, this section of the book presents an accessible and compelling argument for the idea that the wealth of the very rich is generally unearned and undeserved – a function of unequal property rights and power relations...

...Later sections of the book cover the negative effects of inequality on the political process and the environment. Sayer discusses how the very rich use lobbying, political party donations and the ‘revolving door’ to reward cooperative regulators and politicians...

...So what does this book offer that other popular analyses of inequality, austerity and the financial crisis do not? The value of Sayer’s account lies in his readable and persuasive attack on the idea that the very richest have accumulated their wealth fairly and deserve to be allowed to accumulate more...

http://blogs.lse.ac.uk/politicsandpolicy/book-review-why-we-cant-afford-the-rich-by-andrew-sayer/

...Sayer’s framework is particularly relevant as he adopts the view that it is not just today’s international working class that needs to off-load the parasitical elite, but that future generations also depend on the transition to a saner economic paradigm in order to secure a sustainable quality of life. He expresses the supreme challenge of our times in stark terms: ‘capitalism is incompatible with saving the planet’ (p.328). The title encapsulates the author’s conviction that capitalism has outlived any progressive tendencies it might have generated in the past in terms of revolutionising humanity’s productive capacity. The super-rich have jettisoned any form of useful economic agenda that might have had beneficial side-effects for the bulk of the world’s population, and are now blindly pursuing a tunnel-visioned stampede for profits. On this theme, Sayer includes a grimly amusing cartoon by the US illustrator, Robert Mankof, showing a corporate meeting in which one of the participants encourages his colleagues to adopt a not entirely unbelievable viewpoint:

‘And so, while the end of the world scenario will be rife with unimaginable horrors, we believe that the pre-end period will be filled with unprecedented opportunities for profit’ (p.333).

Sayer’s starting point for his radical deconstruction of bourgeois economics is a three-part conceptualisation of the essence of neoliberalism and its associated features that have permeated into the cultural bedrock of our times.

(First), it is based on the claim that markets are the optimal form of economic activity and that they ‘supposedly reward efficiency and penalise inefficiency and thereby incentivise us to improve’ (p.16). The unthinking implementation of this dogma since the 1980s has brought in its wake an assault on the public sector in the form of policies such privatisation, league tables and target-setting; all presided over by a corporate managocracy, devoid of any authentic ethos of the public good.

(Secondly), neoliberalism has shifted the paradigm of our collective consciousness away from the notion of seeing ourselves as part of an inter-dependent social network, and towards the more market-friendly conception of the self as an egocentric consumer. Sayer perceptively notes that the word ‘loser’ has now entered our discourse as a term of abuse, rather than one that might elicit compassion (p.17).

The (third) element of this resurgent ideology is a reconfiguration within the ruling class, in which wealth and status are increasing based on little more than manipulating the financial gyrations of the global market, as opposed to actually producing goods and services like previous generations of the elite...

http://www.counterfire.org/articles/book-reviews/17733-why-we-can-t-afford-the-rich

With wealth goes power: political power. We’ve seen a rise of the rich in politics and the overshadowing of democracy by plutocracy. The global rich and big business are increasingly funding, infiltrating and dominating governments, and rigging the rules of the economy in their favour.

The wealth of the rich is not only ill-gotten, but ill-spent. It’s a waste of resources, and it encourages those with less to emulate them, so production is diverted from producing basic needs to producing under-used luxuries and symbols of opulence. It’s also madly unsustainable. And the rich not only tread most heavily on the planet but many of them have financial interests in continued unsustainable growth and fossil fuel extraction.

https://policypress.wordpress.com/2014/11/25/fact-we-cant-afford-the-rich/

Why We Can't Afford the Rich - The race to get richer and richer needs to end. Wealth needs to be more evenly dispersed in our society.

http://www.alternet.org/books/why-we-cant-afford-rich

No, wealth isn’t created at the top. It is merely devoured there. Bankers, pharmaceutical giants, Google, Facebook ... a new breed of rentiers are at the very top

No, wealth isn’t created at the top. It is merely devoured there. Bankers, pharmaceutical giants, Google, Facebook ... a new breed of rentiers are at the very top of the pyramid and they’re sucking the rest of us dry.

This piece is about one of the biggest taboos of our times. About a truth that is seldom acknowledged, and yet – on reflection – cannot be denied. The truth that we are living in an inverse welfare state.

These days, politicians from the left to the right assume that most wealth is created at the top. By the visionaries, by the job creators, and by the people who have “made it”. By the go-getters oozing talent and entrepreneurialism that are helping to advance the whole world.

Now, we may disagree about the extent to which success deserves to be rewarded – the philosophy of the left is that the strongest shoulders should bear the heaviest burden, while the right fears high taxes will blunt enterprise – but across the spectrum virtually all agree that wealth is created primarily at the top.

So entrenched is this assumption that it’s even embedded in our language. When economists talk about “productivity”, what they really mean is the size of your paycheck. And when we use terms like “welfare state”, “redistribution” and “solidarity”, we’re implicitly subscribing to the view that there are two strata: the makers and the takers, the producers and the couch potatoes, the hardworking citizens – and everybody else.

In reality, it is precisely the other way around. In reality, it is the waste collectors, the nurses, and the cleaners whose shoulders are supporting the apex of the pyramid. They are the true mechanism of social solidarity. Meanwhile, a growing share of those we hail as “successful” and “innovative” are earning their wealth at the expense of others. The people getting the biggest handouts are not down around the bottom, but at the very top. Yet their perilous dependence on others goes unseen. Almost no one talks about it. Even for politicians on the left, it’s a non-issue.

To understand why, we need to recognise that there are two ways of making money. The first is what most of us do: work. That means tapping into our knowledge and know-how (our “human capital” in economic terms) to create something new, whether that’s a takeout app, a wedding cake, a stylish updo, or a perfectly poured pint. To work is to create. Ergo, to work is to create new wealth.

But there is also a second way to make money. That’s the rentier way: by leveraging control over something that already exists, such as land, knowledge, or money, to increase your wealth. You produce nothing, yet profit nonetheless. By definition, the rentier makes his living at others’ expense, using his power to claim economic benefit.

For those who know their history, the term “rentier” conjures associations with heirs to estates, such as the 19th century’s large class of useless rentiers, well-described by the French economist Thomas Piketty. These days, that class is making a comeback. (Ironically, however, conservative politicians adamantly defend the rentier’s right to lounge around, deeming inheritance tax to be the height of unfairness.) But there are also other ways of rent-seeking. From Wall Street to Silicon Valley, from big pharma to the lobby machines in Washington and Westminster, zoom in and you’ll see rentiers everywhere.

There is no longer a sharp dividing line between working and rentiering. In fact, the modern-day rentier often works damn hard. Countless people in the financial sector, for example, apply great ingenuity and effort to amass “rent” on their wealth. Even the big innovations of our age – businesses like Facebook and Uber – are interested mainly in expanding the rentier economy. The problem with most rich people therefore is not that they are coach potatoes. Many a CEO toils 80 hours a week to multiply his allowance. It’s hardly surprising, then, that they feel wholly entitled to their wealth.

It may take quite a mental leap to see our economy as a system that shows solidarity with the rich rather than the poor. So I’ll start with the clearest illustration of modern freeloaders at the top: bankers. Studies conducted by the International Monetary Fund and the Bank for International Settlements – not exactly leftist thinktanks – have revealed that much of the financial sector has become downright parasitic. How instead of creating wealth, they gobble it up whole.

Don’t get me wrong. Banks can help to gauge risks and get money where it is needed, both of which are vital to a well-functioning economy. But consider this: economists tell us that the optimum level of total private-sector debt is 100% of GDP. Based on this equation, if the financial sector only grows, it won’t equal more wealth, but less. So here’s the bad news. In the United Kingdom, private-sector debt is now at 157.5%. In the United States, the figure is 188.8%.

In other words, a big part of the modern banking sector is essentially a giant tapeworm gorging on a sick body. It’s not creating anything new, merely sucking others dry. Bankers have found a hundred and one ways to accomplish this. The basic mechanism, however, is always the same: offer loans like it’s going out of style, which in turn inflates the price of things like houses and shares, then earn a tidy percentage off those overblown prices (in the form of interest, commissions, brokerage fees, or what have you), and if the shit hits the fan, let Uncle Sam mop it up.

The financial innovation concocted by all the math whizzes working in modern banking (instead of at universities or companies that contribute to real prosperity) basically boils down to maximising the total amount of debt. And debt, of course, is a means of earning rent. So for those who believe that pay ought to be proportionate to the value of work, the conclusion we have to draw is that many bankers should be earning a negative salary; a fine, if you will, for destroying more wealth than they create.

Bankers are the most obvious class of closet freeloaders, but they are certainly not alone. Many a lawyer and an accountant wields a similar revenue model. Take tax evasion. Untold hardworking, academically degreed professionals make a good living at the expense of the populations of other countries. Or take the tide of privatisations over the past three decades, which have been all but a carte blanche for rentiers. One of the richest people in the world, Carlos Slim, earned his millions by obtaining a monopoly of the Mexican telecom market and then hiking prices sky high. The same goes for the Russian oligarchs who rose after the Berlin Wall fell, who bought up valuable state-owned assets for song to live off the rent.

But here comes the rub. Most rentiers are not as easily identified as the greedy banker or manager. Many are disguised. On the face of it, they look like industrious folks, because for part of the time they really are doing something worthwhile. Precisely that makes us overlook their massive rent-seeking.

Take the pharmaceutical industry. Companies like GlaxoSmithKline and Pfizer regularly unveil new drugs, yet most real medical breakthroughs are made quietly at government-subsidised labs. Private companies mostly manufacture medications that resemble what we’ve already got. They get it patented and, with a hefty dose of marketing, a legion of lawyers, and a strong lobby, can live off the profits for years. In other words, the vast revenues of the pharmaceutical industry are the result of a tiny pinch of innovation and fistfuls of rent.

Even paragons of modern progress like Apple, Amazon, Google, Facebook, Uber and Airbnb are woven from the fabric of rentierism. Firstly, because they owe their existence to government discoveries and inventions (every sliver of fundamental technology in the iPhone, from the internet to batteries and from touchscreens to voice recognition, was invented by researchers on the government payroll). And second, because they tie themselves into knots to avoid paying taxes, retaining countless bankers, lawyers, and lobbyists for this very purpose.

Even more important, many of these companies function as “natural monopolies”, operating in a positive feedback loop of increasing growth and value as more and more people contribute free content to their platforms. Companies like this are incredibly difficult to compete with, because as they grow bigger, they only get stronger.

Aptly characterising this “platform capitalism” in an article, Tom Goodwin writes: “Uber, the world’s largest taxi company, owns no vehicles. Facebook, the world’s most popular media owner, creates no content. Alibaba, the most valuable retailer, has no inventory. And Airbnb, the world’s largest accommodation provider, owns no real estate.”

So what do these companies own? A platform. A platform that lots and lots of people want to use. Why? First and foremost, because they’re cool and they’re fun – and in that respect, they do offer something of value. However, the main reason why we’re all happy to hand over free content to Facebook is because all of our friends are on Facebook too, because their friends are on Facebook … because their friends are on Facebook.

Most of Mark Zuckerberg’s income is just rent collected off the millions of picture and video posts that we give away daily for free. And sure, we have fun doing it. But we also have no alternative – after all, everybody is on Facebook these days. Zuckerberg has a website that advertisers are clamouring to get onto, and that doesn’t come cheap. Don’t be fooled by endearing pilots with free internet in Zambia. Stripped down to essentials, it’s an ordinary ad agency. In fact, in 2015 Google and Facebook pocketed an astounding 64% of all online ad revenue in the US.

But don’t Google and Facebook make anything useful at all? Sure they do. The irony, however, is that their best innovations only make the rentier economy even bigger. They employ scores of programmers to create new algorithms so that we’ll all click on more and more ads. Uber has usurped the whole taxi sector just as Airbnb has upended the hotel industry and Amazon has overrun the book trade. The bigger such platforms grow the more powerful they become, enabling the lords of these digital feudalities to demand more and more rent.

Think back a minute to the definition of a rentier: someone who uses their control over something that already exists in order to increase their own wealth. The feudal lord of medieval times did that by building a tollgate along a road and making everybody who passed by pay. Today’s tech giants are doing basically the same thing, but transposed to the digital highway. Using technology funded by taxpayers, they build tollgates between you and other people’s free content and all the while pay almost no tax on their earnings.

This is the so-called innovation that has Silicon Valley gurus in raptures: ever bigger platforms that claim ever bigger handouts. So why do we accept this? Why does most of the population work itself to the bone to support these rentiers?

I think there are two answers. Firstly, the modern rentier knows to keep a low profile. There was a time when everybody knew who was freeloading. The king, the church, and the aristocrats controlled almost all the land and made peasants pay dearly to farm it. But in the modern economy, making rentierism work is a great deal more complicated. How many people can explain a credit default swap, or a collateralised debt obligation? Or the revenue model behind those cute Google Doodles? And don’t the folks on Wall Street and in Silicon Valley work themselves to the bone, too? Well then, they must be doing something useful, right?

Maybe not. The typical workday of Goldman Sachs’ CEO may be worlds away from that of King Louis XIV, but their revenue models both essentially revolve around obtaining the biggest possible handouts. “The world’s most powerful investment bank,” wrote the journalist Matt Taibbi about Goldman Sachs, “is a great vampire squid wrapped around the face of humanity, relentlessly jamming its blood funnel into anything that smells like money.”

But far from squids and vampires, the average rich freeloader manages to masquerade quite successfully as a decent hard worker. He goes to great lengths to present himself as a “job creator” and an “investor” who “earns” his income by virtue of his high “productivity”. Most economists, journalists, and politicians from left to right are quite happy to swallow this story. Time and again language is twisted around to cloak funneling and exploitation as creation and generation.

However, it would be wrong to think that all this is part of some ingenious conspiracy. Many modern rentiers have convinced even themselves that they are bona fide value creators. When current Goldman Sachs CEO Lloyd Blankfein was asked about the purpose of his job, his straight-faced answer was that he is “doing God’s work”. The Sun King would have approved.

The second thing that keeps rentiers safe is even more insidious. We’re all wannabe rentiers. They have made millions of people complicit in their revenue model. Consider this: What are our financial sector’s two biggest cash cows? Answer: the housing market and pensions. Both are markets in which many of us are deeply invested.

Recent decades have seen more and more people contract debts to buy a home, and naturally it’s in their interest if house prices continue to scale new heights (read: burst bubble upon bubble). The same goes for pensions. Over the past few decades we’ve all scrimped and saved up a mountainous pension piggy bank. Now pension funds are under immense pressure to ally with the biggest exploiters in order to ensure they pay out enough to please their investors.

The fact of the matter is that feudalism has been democratised. To a lesser or greater extent, we are all depending on handouts. En masse, we have been made complicit in this exploitation by the rentier elite, resulting in a political covenant between the rich rent-seekers and the homeowners and retirees.

Don’t get me wrong, most homeowners and retirees are not benefiting from this situation. On the contrary, the banks are bleeding them far beyond the extent to which they themselves profit from their houses and pensions. Still, it’s hard to point fingers at a kleptomaniac when you have sticky fingers too.

So why is this happening? The answer can be summed up in three little words: Because it can.

Rentierism is, in essence, a question of power. That the Sun King Louis XIV was able to exploit millions was purely because he had the biggest army in Europe. It’s no different for the modern rentier. He’s got the law, politicians and journalists squarely in his court. That’s why bankers get fined peanuts for preposterous fraud, while a mother on government assistance gets penalised within an inch of her life if she checks the wrong box.

The biggest tragedy of all, however, is that the rentier economy is gobbling up society’s best and brightest. Where once upon a time Ivy League graduates chose careers in science, public service or education, these days they are more likely to opt for banks, law firms, or trumped up ad agencies like Google and Facebook. When you think about it, it’s insane. We are forking over billions in taxes to help our brightest minds on and up the corporate ladder so they can learn how to score ever more outrageous handouts.

One thing is certain: countries where rentiers gain the upper hand gradually fall into decline. Just look at the Roman Empire. Or Venice in the 15th century. Look at the Dutch Republic in the 18th century. Like a parasite stunts a child’s growth, so the rentier drains a country of its vitality.

What innovation remains in a rentier economy is mostly just concerned with further bolstering that very same economy. This may explain why the big dreams of the 1970s, like flying cars, curing cancer, and colonising Mars, have yet to be realised, while bankers and ad-makers have at their fingertips technologies a thousand times more powerful.

Yet it doesn’t have to be this way. Tollgates can be torn down, financial products can be banned, tax havens dismantled, lobbies tamed, and patents rejected. Higher taxes on the ultra-rich can make rentierism less attractive, precisely because society’s biggest freeloaders are at the very top of the pyramid. And we can more fairly distribute our earnings on land, oil, and innovation through a system of, say, employee shares, or a universal basic income.

But such a revolution will require a wholly different narrative about the origins of our wealth. It will require ditching the old-fashioned faith in “solidarity” with a miserable underclass that deserves to be borne aloft on the market-level salaried shoulders of society’s strongest. All we need to do is to give real hard-working people what they deserve.

And, yes, by that I mean the waste collectors, the nurses, the cleaners – theirs are the shoulders that carry us all.

Thom Hartmann on Capital & Taxes

Closing Borders Won't Fix Inequality

Economists: Closing Borders Won't Fix Inequality. Enthusiasm for inward-looking, protectionist economic agendas is growing in the U.S. as well as Europe.

Clearly, the experience of the past three decades of globalization has produced massive dissatisfaction: so much that naive, misplaced and often frightening measures are seen as genuine solutions by large parts of the electorate in the richest nations of the world.

What needs to be asked is the following: why is the world economy at this pass? Is it a labor-versus-labor problem? Would shutting borders lead to greater equality of incomes within countries? Would the poor and working class in developed countries, who are feeling the heat of unemployment, depressed wages and insecure futures, regain their (mostly imagined) former glory if their countries shut down their borders?

Or is it the case that gains from globalization, instead of trickling down, have been sucked upwards towards a tiny elite, making an already rich minority even richer? And that this elite resides within, not outside, their countries?

Global inequality on the decline while inequality within the developed world is increasing

Much of the political and broader discussion of economic inequality has been focused on inequality within countries, but Oxfam's report focuses on comparing wealth globally. In this case, the focus on global inequality is a red herring.

Global inequality has actually been on the decline while inequality within the developed world is increasing. But that wouldn't necessarily be the quick takeaway from the Oxfam report, which presents a false narrative about trends in inequality. Why should this matter? Because a widely accepted misperception can lead to policy proposals that fail to address the problem of rising inequality within nations.

Inequality vs Fairness

The science of inequality: why people prefer unequal societies. In a thought-provoking new paper, three Yale scientists argue it’s not inequality in life that really bothers us, but unfairness.

The data show a surprising pattern: The more unequal a society, the less likely its citizens are to notice. Paradoxically, citizens in some of the most unequal countries think theirs is the paragon of meritocracy. How can we explain this phenomenon?

toxic inequality

Since the Great Recession, most Americans' standard of living has stagnated or declined. Economic inequality is at historic highs. But inequality's impact differs by race; African Americans' net wealth is just a tenth that of white Americans, and over recent decades, white families have accumulated wealth at three times the rate of black families. In our increasingly diverse nation wealth disparities must be understood in tandem with racial inequities--a dangerous combination he terms "toxic inequality."

In Toxic Inequality, Shapiro reveals how these forces combine to trap families in place. Following nearly two hundred families of different races and income levels over a period of twelve years, Shapiro's research vividly documents the recession's toll on parents and children, the ways families use assets to manage crises and create opportunities, and the real reasons some families build wealth while others struggle in poverty. The structure of our neighborhoods, workplaces, and tax code-much more than individual choices-push some forward and hold others back. A lack of assets, far more common in families of color, can often ruin parents' careful plans for themselves and their children.

Toxic inequality may seem inexorable, but it is not inevitable. America's growing wealth gap and its yawning racial divide have been forged by history and preserved by policy, and only bold, race-conscious reforms can move us toward a more just society.

Toxic Inequality: How America’s Wealth Gap Destroys Mobility, Deepens the Racial Divide, and Threatens Our FutureHardcover – March 14, 2017 by Thomas M. Shapiro

https://www.amazon.com/Toxic-Inequality-Americas-Destroys-Threatens/dp/0465046932

Status anxiety’ and ‘image anxiety’

Status anxiety’ and ‘image anxiety’ were repeatedly mentioned by the listening experts, as symptoms of our materialistic, image-conscious times. While this impacts us all, young people are particularly afflicted, with one in eight British children affected by anxiety disorders according to The Guardian.

Research shows that children with untreated anxiety disorders are at higher risk to perform poorly in school, miss out on important social experiences, and engage in substance abuse.

https://www.opendemocracy.net/graham-peebles/anxiety-in-age-of-inequality

The Vicious Circle Of Inequality

...the medieval world. Since the economy isn´t growing by any other means than population growth, the only way to become wealthier is to redistribute income, in effect taking your neighbor’s land.

This will, of course, also determine which types of investment are profitable. For grabbing your neighbor’s land you need political support (legitimacy) from those who control property rights (i.e. the king) and your own military force. Since larger armies tend to beat smaller ones, and the same goes for bribes, the system favors concentration of power and income – the rise of the rich and the mighty noble. The king, however, doesn´t just give political protection; he also needs it from his noble friends...

Medieval Relations

Unfortunately, the vicious circle of inequality seems a rather good description of what’s going on now. Since the seventies, growth in both machines (real investments) and knowledge (human capital) has fallen. Investments in politics have on the other hand increased sharply, with the US Presidential campaign the most stunning example. The political preferences of the new patrons of politics for fewer taxes and upwards redistribution have also been very popular the last two decades among European politicians. After the mid-1990s inequality trends have mainly been driven by reduced public redistribution, not market forces...

https://www.socialeurope.eu/vicious-circle-inequality