Why You Were Born to Gossip | Psychology Today

If evolutionary psychologist Robin Dunbar is right,

Gossip is exciting, even when the events discussed are mundane, and

swapping stories during talk-in-interaction is probably -

since gossip provides us with useful information about people in our social network, the holder of a juicy tidbit gains social capital by selectively sharing it with others.

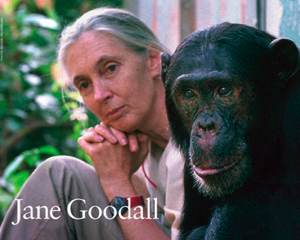

It’s hard to imagine two humans building a relationship without ever speaking to each other. And yet our chimpanzee cousins build complex social networks without uttering a word. Chimpanzee vocalizations clearly play a social role, particularly laughter. While vocalizations help cement group cohesion, one-on-one relationships are built through other means.

In the primate world -friendships are maintained through the practice of picking fleas and dirt from the fur of other members in the group - Known as social grooming, it’s quite literally a “you scratch my back and I’ll scratch yours” kind of relationship. Although grooming does serve a hygienic purpose, cleaning the fur and skin of insects and debris, it also solidifies friendships.

Humans also engage in social grooming—doing each other’s hair, primping each other’s clothes. But according to Dunbar, we’ve found an easier, more effective way of building and maintaining relationships - idle chit-chat. In other words,

for us - gossip serves the same purpose of -

social network building as does mutual grooming for chimpanzees...

https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/talking-apes/201502/why-you-were-born-gossip

A Couple of Chimps Sitting Around Talking

Robin Dunbar, a professor of psychology at the University of Liverpool, offers an evolutionary explanation for another of our guilty little pleasures: gossip. No matter how lofty our intellectual aspirations, we are chatterers and snoops every one of us, greedy for stories about friends, relations, rivals, fictional characters, O. J. Simpson.

As Mr. Dunbar notes at the outset of 'Grooming, Gossip, and the Evolution of

Language,' his systematic eavesdropping has shown that

A heated exchange about politics, philosophy or the latest soccer match might occasionally intervene, but within five minutes, the author says, the discussion returns to "the natural rhythms of social life."

Mr. Dunbar argues that -

At the heart of this fresh and witty book is the thesis that;

Gossip is the human version of primate grooming.

Apes and monkeys spend many hours stroking one another's fur, the author explains, and they're not doing it for the sake of public hygiene. Long after a chimpanzee or gorilla has picked out every last flea and tick from a fellow's coat it will continue to pet, scratch, nibble and pinch. It will groom until the object of its attentions is practically falling over with drunken pleasure.

That primates devote effort to grooming that in theory would be more productively spent foraging or mating means the practice must be essential. And so it appears that grooming is the key to primate group life.

Most species of apes and monkeys live in groups, the better to defend territory, hunt, watch for predators and protect the young. Yet as any high school student knows, social life offers its own pitfalls. Snobs snub you, bullies push you around. Primates cope with the crowd by grooming. Whether to cement family ties, solicit new allies or apologize after a quarrel, they groom. Without constant mutual stroking, the primate social pact might soon dissolve.

But there's one big drawback to grooming, Mr. Dunbar says. It takes too much time. As the social lives of early hominids grew increasingly complex and their group size expanded, they could no longer afford to keep in touch, literally, with every last kin and comrade.

They needed a more efficient means of socializing. Hominids already knew how to make noises; why not organize those noises into recognizable patterns?

As a social device, speech offers numerous advantages over grooming;

- You can speak to several individuals simultaneously, and

- You can convey information over a wider network of individuals

- Speaking takes less time than grooming, and

- You can do it while engaged in another task, like gathering food.

The putative link between gossip and grooming helps explain why gossip feels good enough to call "juicy." A chimpanzee being groomed is a creature awash in opiates, the body's natural tranquilizers. Assuming that gossip subserves the same neural structures as grooming does, it too may stimulate opiate production.

To buttress his argument that language arose for the sake of socializing, Dunbar offers comparative data between the brain size of different primates and the size of the groups in which they live. He has found a tidy trend suggesting that;

as the social group gets larger, so too does the volume of neocortex, the newest and so-called ''thinking'' part of the brain.

The human neocortex is four times bigger than that of our closest relative, the chimpanzee. Plugging the data into his chart,

Dunbar predicted that -

- Modern hunter-gatherer tribes... live in groups of about 150.

- Church congregations,

- Military companies,

- Divisions of corporations,

- Hutterite villages,

- The number of acquaintances that the average person knows,

All are close to the magic sum of 150. The size seems to fit well with the human psyche, offering both interest and intimacy.

Mr. Dunbar proposes that our forebears at some point began expanding their group size beyond chimplike dimensions to cope with changing environmental conditions and increased competitive pressures.

As group size expanded, the need for a grooming substitute arose, and language proved the solution.

When language arose neither the author nor anybody else can say for sure, but Mr. Dunbar suggests that the emergence of Homo sapiens, about 500,000 years ago, was marked by the appearance of language.

''Grooming, Gossip, and the Evolution of Language'' is in many ways a wonderful book, and its ideas deserve an airing. Mr. Dunbar is a clear thinker and a polymath, marshaling evidence for his thesis from such varied fields as primatology, linguistics, anthropology and genetics.

https://archive.nytimes.com/www.nytimes.com/books/97/03/09/reviews/

Wikipedia - Grooming, Gossip and the Evolution of Language

Dunbar argues that gossip does for group-living humans what manual grooming does for other primates—it allows individuals to service their relationships and thus maintain their alliances on the basis of the principle: if you scratch my back, I'll scratch yours. Dunbar argues that as humans began living in increasingly larger social groups, the task of manually grooming all one's friends and acquaintances became so time-consuming as to be unaffordable. In response to this problem, Dunbar argues that humans invented 'a cheap and ultra-efficient form of grooming'—vocal grooming. To keep allies happy, one now needs only to 'groom' them with low-cost vocal sounds, servicing multiple allies simultaneously while keeping both hands free for other tasks. Vocal grooming then evolved gradually into vocal language—initially in the form of 'gossip'. Dunbar's hypothesis seems to be supported by the fact that the structure of language shows adaptations to the function of narration in general...https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Grooming,_Gossip_and_the_Evolution_of_Language

Book Review: Decoding Evolutionary Roots of Human Social Behavior

Decoding Evolutionary Roots of Human Social Behavior is a review and

analysis of Grooming, Gossip, and the Evolution of Language (and the human

brain). Having been immersed in experiential social media since 2006, I’ve

increasingly turned to evolutionary psychology to understand human behavior

at a much deeper level: by studying primates, I get much closer to the root

causes of human behavior, and this book was my introduction to the field.

Decoding Evolutionary Roots of Human Social Behavior is a review and

analysis of Grooming, Gossip, and the Evolution of Language (and the human

brain). Having been immersed in experiential social media since 2006, I’ve

increasingly turned to evolutionary psychology to understand human behavior

at a much deeper level: by studying primates, I get much closer to the root

causes of human behavior, and this book was my introduction to the field.

Inside Human OS—The Roots of Facebook Behavior Revealed by Primate Professor

Digital social networks give their members front row seats in many aspects of human dramas, but few companies or individuals have the understanding of human behavior to appreciate fully what they are seeing. Many executives of commercial and government enterprises perceive “social” behavior as frivolous and discourage employees’ activity in social networks. This exceptional book shows that the Industrial Economy idea of the separation of “work” and “social” is dangerously out of place in the Knowledge Economy, in which collaboration among people produces the lion’s share of business value. To succeed in the Knowledge Economy, leaders need to appreciate the importance of social activity in collaboration and productivity, and how digital social networks can increase productivity. In this review, I will try to do the book justice, but I will also attempt to show how its ideas apply to digital social networks, collaboration and productivity.

To use a technical metaphor, Windows has its DOS, and Mac OS X has its UNIX. In fact, Windows and Mac OS X are just interfaces that come between the core engine (DOS and UNIX) of the computer and the user, so s/he doesn’t have to have technical knowledge to run the machine. However, at critical moments, it can be very advantageous to understand certain aspects of the core operating systems. Since understanding human behavior is critical to success in virtually all human endeavors, it might be useful to understand what I’ll term as “Human OS.” This enthralling book gets way under the covers on “social” network behavior and puts it all into perspective. As such, readers come to appreciate how and why people behave the way they do.

Book Overview

Grooming, Gossip, and the Evolution of Language, by Robin Dunbar, is one of the most relevant and fascinating books I have read this decade. It reveals “Human OS” (human operating system) in an insightful, engaging way that Dunbar backs with extensive primary and secondary research into primate behavior. I have a very practical interest in Human OS: if digital social networks like LinkedIn, Facebook, Orkut and YouTube diminish the transaction costs of certain human interactions, logic holds that tremendous insight into motivations and likely uses of the networks would be gleaned by understanding Human OS. For people who want to pop the bonnet and delve into human motivations within group dynamics in digital social networks, Grooming, Gossip, and the Evolution of Language will prove an invaluable guidebook. A tremendous plus: the book is as readable as it is revealing.

As a pioneer in using digital social networks for organizational innovation, I constantly see references to “Dunbar’s Number,” which holds that humans have a practical limit to the number of acquaintances they may have in the traditional sense. Grooming, Gossip.. puts it into a rich context. But there is far more. Grooming and gossiping are core processes in Human OS, and social networks enable them in ways that confound business executives. Dunbar shows conclusively that, on average, two thirds of all human communication is “social”: talking about others and ourselves. Digital social networks are disconcerting to many because they reveal this. The most hits, the most popular videos and blog posts are often idiotic from a “serious” business point of view. Grooming, Gossip.. reveals why this makes sense, and it is a shortcut to making sense of Human OS, taking it seriously and loving it. The people and organizations that are willing to engage Human OS will succeed far more.

As in all Global Human Capital book reviews, I will summarize and outline each chapter before drawing my Analysis and Conclusions below. Note that I only give the most important books this detailed treatment. My hope is that you will appreciate the review and buy the book because it makes Human OS so accessible, fascinating and useful.

Chapter One: Talking Heads

In this introductory chapter, Dunbar connects several branches of science in the service of understanding why humans have language. By mashing up evolutionary biology, anthropology, social behavior and linguistics, he leads us down a path that does not presuppose that we should have language. There should be undeniable practical reasons that we have language and large brains.

- Introduces “grooming” and gestures and their importance to primates in the context of social groups.

- Tantalizing facts about the brain: it consumes 20% of our total energy, while it accounts for 2% of our body weight. Why do we have such an expensive piece of equipment?

- Although dolphins have roughly the same brain/body ratio, they do not come close to humans in their language. Why?

- About two thirds of all human language is social in nature: who does what with whom, why it’s important or not. Dunbar shares studies that show this ratio holds true in the boardroom, on the engineering team and university professors’ lounges. He also cites publishing, newspapers.

- Language and linguistics have been traditionally viewed as “social” sciences, so biologists and evolutionologists stayed away; Dunbar will weave these together.

“The story is a magical mystery tour that will take us bounding from one unexpected corner of our biology to another, from history to hormones, from the very public behavior of monkeys and apes to the moments of greatest human intimacy.”

Chapter Two: Into the Social Whirl

Chapter Two is a crash course in the social group dynamics and economics of

primates because Dunbar wants to take us on the level of Human OS, and we

are primates. More depth on the role of grooming and social status.

Chapter Two is a crash course in the social group dynamics and economics of

primates because Dunbar wants to take us on the level of Human OS, and we

are primates. More depth on the role of grooming and social status.

- Our primate lineage, and how surprisingly short it is: only about 350,000 people separate us all from our “ancestral eve.” Another 350,000, and we are back to the ancestor we share with today’s “common chimpanzee.”

- Some primate economics: finding food, human biology, how and why we were incented to grow to our body size and live in groups to reduce the risk of being killed by predators.

- How being social is hard-wired into our DNA.

- The two poles: we need the group to survive, but overcrowding compels us to seek the “sanity of a solitary life.” It turns out that we manage this dichotomy by creating partnerships, coalitions and cliques.

- How alliances work: Dunbar shares his observations of primates in such a way that it’s easy to see the applicability to human behavior. Windows into primates’ calculus when building alliances: how primates infer and predict others’ behavior in certain situations by observing their social behavior. Quote from Chimpanzee Politics. Grooming’s role in compromises and reconciliations between alliance partners.

- The role of grooming in building and maintaining primates’ alliances.

- The link to Darwinian evolutionary theory: the ultimate pattern of “meritocracy”: reproductive success by successful adaptation to changing circumstances.

“Sociality is at the very core of primate existence; it is their principal evolutionary strategy, the thing that marks them out as different from all other species. It is a very special kind of sociality, for it is based on intense bonds between group members, with kinship often providing a platform for these relationships.”

Chapter Three: The Importance of Being Earnest

Dunbar covers a lot of ground here, everything from deception within a group to grooming’s physiological effects on us to why it is so effective for maintaining alliances.

- In primates, how much time a pair spend grooming each other is proportional to each partner’s willingness to defend the other. Grooming is a mutually exclusive activity, and everyone sees who is grooming whom.

- It also turns out that grooming triggers our brains to produce endorphins (we get high); he references some interesting research to confirm the point. Astonishing fact: many primates spend roughly 20% of their time on grooming, which indicates that it plays an enormous role in their (our) well-being. The bigger the network, the more grooming required.

- More on the economics of group size and interaction, and harassment’s impact on reproduction. You guessed it: low-ranking females, because they are harassed by the majority of the group, experience temporary infertility due to the stress harassment produces. Mental and social intimidation are more lethal than physical abuse because the victim uses the stimulus and takes it against herself. Fertility is also reduced in males under stress. The net-net here is, large groups mean more harassment even while they afford more protection against predators. It turns out that alliances are how group members diminish harassment.

- Freeloading is another problem for large groups: freeloaders take something and promise to return the favor later but never do. Within large groups, they can trick and move on before they are found out. In this case, grooming is the cost of entry for alliances: by imposing a high cost in a visible behavior, freeloading is reduced.

- Dunbar closes by citing research that shows that many species have sophisticated communication that approaches rudimentary language (for example, specific sounds identify specific predators).

“The solution of choice is, it seems, to form coalitions (which) allow you to defuse the opposition (harassment)… Forming a coalition with someone else allows you to act in mutual defence, so reducing the frequency and intensity of harassment without driving your harassers (completely) away.”

Chapter Four: Of Brains and Groups and Evolution

Begins with an irresistible question: why do monkeys have big brains?

- Research on brain/body mass and Dunbar’s breakthrough, showing that neocortex size and group size have a causality. The idea: our brains are bigger because we have been forced to be social as an adaptive mechanism. Moreover, the Machiavellian hypothesis suggests primates don’t only need to remember how each member of the group relates to other members, they need to anticipate behavior given (often) hypothetical situations because they are in competition with each other, and life is about juggling goals of oneself versus others. They need to maintain a balance between numerous conflicting interests. This is a strong motor for intellectual development.

- Dunbar’s number, which holds that the optimal group size for humans is 150, as a function of the human brain’s capacity. Interesting property: in a group, it’s the average size of four generations of an ancestral couple’s offspring, using data from hunter-gatherer societies, using hunter-gatherer family sizes.

- Introduces the dilemma: bigger groups require more grooming to maintain the group’s structure, but there’s not enough time in the day to do it physically. This leads to the question: could language serve as a kind of vocal grooming?

“Homo sapiens first appeared as long as 400,000 years ago. Throughout that long time-span, right up until the appearance of agriculture a mere 10,000 years ago, we lived as hunter-gatherers in small bands wandering through the woodlands in search of game.”

“In a nutshell, I am suggesting that language evolved to allow us to gossip.” (This drove the need for infrastructure, i.e., our brain and body size.)

Chapter Five: The Ghost in the Machine

This is all about Theory of Mind (ToM) and how the brain works. ToM holds that a (person) recognizes that someone else can have different thoughts and beliefs from his own. This gets into trust and deception.

- Theory of Mind (ToM) applied to primates. No, humans are by no means alone here. Dunbar shares numerous hilarious and instructive examples of chimpanzees and apes that anticipate each other’s behavior in the service of competition and trickery.

- Think of the last time you observed humans observing chimpanzees, orangutans or gorillas at the zoo; there is a marvelous fascination and a connection. Grooming, Gossip.. taps into that marvel throughout. It’s filled with hilarious anecdotes of antics of our primate cousins, but Dunbar skillfully remains on task to drive the point home.

- How and when human children develop ToM.

- The cases of autism and Asperger’s to illustrate human development.

- The root of abstract thought and the ability to understand others.

“… the ability to use subtle social strategies and to exploit loopholes in the social context depends on how much computing power you have available in your brain.”

Chapter Six: Up Through the Mists of Time

Chapter Six is spellbinding. It returns to the savannah some five million years ago and offers a more complete pass at human evolution, from the perspective of the brain (and by extension, the body): group economics, grooming and language. Dunbar cites numerous studies to make his points.

- The brain demands too much energy from the body: how did we accommodate the energy hungry brain (20% all energy)? There were very few choices: vital organs were, well, vital, so they would not give energy to the brain. The most expedient deal evolution could cut was with the gut (stomach and intestines). In fact, humans have much smaller guts than they should, given body size. Dunbar gives us a fascinating discussion of various primates, diets and gut sizes.

- We learn that “normal” human babies are born twelve months premature, as a function of brain size. However, humans had severe evolutionary constraints in their body and brain sizes that relatively large brains and small bodies (think the mother here). We needed large brains to manage large groups, but the large brain meant that some other part of our anatomy had to give up its demands, and that was the gut. The elephant’s brain is roughly the same size as ours; that’s what I mean by having a relatively small body. Compared to other species, our brain develops extensively after birth, and human babies are much more helpless than other species’.

- The only way the calculus worked was by changing the diet to more energy rich food that demanded less work to process. That meant meat. Notably, we ate other humans, especially early on.

- Interesting chart showing group size increasing during primate evolution. Surprise regarding Neanderthals.

- Group size revisited: discussion about discussion group sizes, location and language.

- Meat moved humans toward more monogamous relationships because males could only support one or two females in most cases. It also enabled humans to migrate.

- Cro-Magnon grew to dominate because s/he was a hunter, moved about and had a relatively diverse network when compared to Neanderthal, who stayed closer to home and had smaller networks.

“The fate of the Neanderthals (being displaced by Cro-Magnon invaders) bears an uncanny resemblance to the fate of the American Indians and the Australian Aborigines at the hands of the later Europeans, invaders who could draw on a larger and more widely distributed political and military power base.”

Chapter Seven: First Words

Here Dunbar returns to the origins of language in more detail.

- Some interesting anatomical details: what’s required to develop the ability to produce words? What do humans have that other primates lack?

- Several theories of language: song, gestures, dance.

- How and why language emerged: the hunting hypothesis.

- Dunbar’s hypothesis: female bonding and relationships were the deciding factor.

- Large groups demanded that humans exchange social information about others (“gossip”) that were not in their immediate sphere so that group members could anticipate their behavior in certain circumstances (“she will go to bat for me in some situations” but not others, based on her interactions with other group members). In the immediate sphere around each member, members see each other’s interactions constantly and have to infer less about each other’s behavior (they know each other better).

- Think about this: although disparaged by many, gossip is about how other people act in discrete social situations with other people, which enables gossipers to formulate opinions about how the gossipees might act in future situations with them or people they care about. Gossip often seems ugly and small, but it is a vital tool for risk management and trust.

“… there appears to be a limit on the number of people we can bond with… (the so-called ‘sympathy group’ of 10 to 15). Managing our relationships with the outer circle of acquaintances depends much more heavily on social knowledge than on emotional empathy.”

Chapter Eight: Babel’s Legacy

Chapter Eight drills down into the development of language and dialects, as well as the practical uses for dialects.

- The life cycles of languages and dialects: cites studies that show that most humans today come from the same stock. Tracing major human migrations and evolutions of languages.

- The importance of kin selection: several studies that show that people live out Darwinian principles in two ways: reproducing themselves andhelping their kin reproduce. The closer the kin, the better. Hamilton’s Rule, which describes the conditions under which one person will help another.

- Presents the observation that dialects develop quickly and continuously, and explores the reasons for this. Dialects are fast-moving trains.

- Surprise: other animals (birds) have dialects, too, and for the same reasons.

- The importance of dialects: they tie people to a place, time and group, and they are difficult to fake. They make it very difficult for freeloaders. They make it possible to distinguish whether a person is “one of us.” Until recently, when people were tied to a time, place and group, the incidence that they were some relation was quite high.

- I have discovered this when learning foreign languages. When you learn and use familiar idiomatic expressions, you quickly get promoted to another level with native speakers. It shows that you have spent considerable time in familiar groups who only use idioms with each other in more intimate situations. Note, it’s not only the expressions themselves; even more important is using them in the right context (this nuance is harder to fake).

- Therefore, language and dialect are mechanisms for risk mitigation when dealing with people. Fascinating, too, that group motivation to “serve the genes.”

“… the rate at which dialects evolve is not constant, but is directly related to population density. The higher the density of people, the faster their dialects change.”

Chapter Nine: The Little Rituals of Life

A fascinating survey of key elements of human life from an evolutionary perspective. Humans as primates and gene-bearers. This is about the stakes of survival, punctuated by interesting studies that describe behavior.

- Gossip: a way to flush out freeloaders and social cheats.

- Cooperativeness within the group is the human evolutionary strategy.

- Explores three purposes of language: keep in the loop about what friends and allies are doing, exchange of information about freeloaders and influencing what others think about us (reputation management).

- Advertising, but from a primate point of view. Dunbar cites a study he directed with these findings: both human sexes spend as much time discussing personal relationships and others’ behaviors. Out the window that “gossip” is mostly a female activity! However, males’ conversations showed an important change. In male-only conversations, art, politics and academic topics averaged 0-5%, but when males were in mixed company, these topics increased to 15-20% of topics. Conclusion, males were showing off.

- Further, female social conversation was dominated by networking, two thirds of their social conversation was about other people. Among males, two thirds of social conversation was about themselves. Conclusions: females are more cooperative, males more competitive because they are vying for mating opportunities.

- The role of hunting big game: not primarily for food, but advertising one’s genes. The role of “heroic” deeds in attracting better genes for mating.

- Non-verbal communication in primates. Eye contact.

- Smiling and laughing: its importance in group dynamics. They also release endorphins. Different types of smiles and laughs, and who typically laughs at whose jokes and why.

- How males and females learn accents: motivations in terms of group dynamics. The wealth of the father has traditionally had a direct correlation with the survival of the offspring. Females almost always try to marry up, so they prepare verbally for that possibility. Lower class males have fewer resources and are more dependent on their networks to provide and protect opportunity.

- Of course, this is all changing with dual income families, and females are now looking for males who have more domestic interests.

- Language as a tool for scaling grooming: can we groom at a distance by using language? Yes.

“By exchanging information on (freeloaders’) activities, humans are able to use language both to gain advanced warning of social cheats and to shame them into conforming to accepted social standards when they do misbehave” (a key function of gossip and social networking, where customers increasingly keep companies in line).

Chapter Ten: The Scars of Evolution

Chapter Ten discusses some implications of the book on how people live today, so it is less factual and more exploratory. In a sense, it is more directly relevant to digital social networks. Dunbar wrote Grooming, Gossip… in 1998, and his discussion of some “modern” modes of communication is on point. A quick tour through modern communication situations, in group dynamics.

- Some observation of people speaking in groups; the magic number here is four; male and female patterns; committees, conference calls. How traditions evolved to enable people to be heard in groups.

- Modern life, and coping with the lack of kin; people are not designed for modern life, as kin are increasingly distant. Fragmentation.

- Lack of kinship has a negative impact on physical health; cites studies of groups in nineteenth century London and the American west that show members with no kin present are more likely to die or be killed.

- Business networks in companies, and the Internet. Road rage and Net rage due to the lack of social cues.

- Short story about a TV production company whose productivity fell precipitously when the company changed offices; architects had eliminated the coffee lounge, which had served as the grapevine. A nice example that shows that seemingly “idle” talk is necessary for groups to function optimally.

- Grooming, Gossip… was written before the advent of digital social networks, so I will fuse the two together in Analysis and Conclusions.

“… social group size appears to be limited by the size of the species’ neocortex; the size of human social networks appears to be limited for similar reasons to around 150; the time devoted to social grooming .. is directly related to group size because it plays a crucial role in bonding groups; language evolved to replace social grooming because it allows us to use the time we have .. more efficiently.”

Analysis and Conclusions

Key Points

If you are interested in human behavior and motivations, I hope you can see that Grooming, Gossip, and the Evolution of Language is an immensely important and valuable book. Here I will focus the book’s implications more directly on digital social networks (hereafter “social networks”). Before delving into that, here are the critical points of the book that you need to understand to appreciate the opportunity presented by social networks.

- Historically, social behavior is the defining element of Human OS and humans’ key evolutionary strategy: “social” is hard-wired into our DNA. Executives who dismiss “social” networks take heed: we primates are group animals, and we owe our brain and body size to our need to be social as a means to survive. “Social” things may seem inane, but get over it, it’s how we are.

- Grooming is the core activity to managing our relationships, and social networks enable us to groom each other. Interactions in digital social networks are all about grooming, LinkedIn Recommendations, writing on Facebook Walls, tagging people in Facebook photos, these are all instances of digital grooming.

- Gossip is mission-critical to Human OS because it is our way to assess and understand the behavior of others whom we don’t know well enough to anticipate their behavior. Therefore, it is in everyone’s best interest to gossip.

- Social networks enable us to change some of the economics of networks because they put many of the mechanisms Dunbar describes online, enabling the digital multiplier. For a business treatment, see How Social Networks Make Markets More Efficient for Buyers and Sellers.

Applying Human OS to Digital Social Networks

-

Social networks are one of the most disruptive phenomena to emerge in

modern society because they raise the prospect that people can

fundamentally change the number and nature of their relationships. They

may prove to be a significant upgrade to Human OS. Language was a tool

that enabled people to scale their grooming activities and expand their

networks (we jumped to another S-curve), and social networks represent a new tool that will lead to even larger

networks.

Social networks are one of the most disruptive phenomena to emerge in

modern society because they raise the prospect that people can

fundamentally change the number and nature of their relationships. They

may prove to be a significant upgrade to Human OS. Language was a tool

that enabled people to scale their grooming activities and expand their

networks (we jumped to another S-curve), and social networks represent a new tool that will lead to even larger

networks.

- Social networks are a digital mirror of Human OS in action, and they expose many aspects of the full spectrum, from “flattering” to “pretty seedy” ,-). I don’t think many “serious” people would like to admit that two thirds of human interaction is gossiping, silly jokes and verbal grooming. This confronts us with who we are versus how we want to see ourselves.

- As Clotaire Rapaille explains passionately, we make decisions with the reptilian brain and justify our decisions with the cortex (intellectual). While reading Grooming, Gossip.. I kept thinking about this; one of Rapaille’s key points is that we like to think of ourselves as rational people, but we are actually quite instinctual and emotional.

- Although Dunbar does not discuss at length “levels” of networks within the 150 limit, he states that we use social information to infer potential behaviors of people. The further away from us, the looser the tie and the more we must infer. Social networks will enable us to have much larger networks of loose connections.

- However, as Dunbar persuasively points out, the human brain remains the bottleneck to expanding our networks. It has a limited capacity to learn and maintain information, social information, trust and relationship about people in order to maintain much larger networks. Remember, social information is filled with nuance and complexity, so I doubt that computers will be able to help to scale Dunbar’s Number in the near term. How can a machine help individuals to ascertain whether another person is trustworthy under specific circumstances? That’s what gossip does for us.

- That said, there is a significant opportunity to create larger networks of relationships in different categories (also see Countering Social Networks’ Unique Challenges with the Relationship Life Cycle).

Key Observations about Social Networks

LinkedIn, Facebook, MySpace, Friendster, Orkut, Xing, Cyworld, Qzone and others have certain features that seek to automate social behavior that their members want, and many executives see this proposition as silly or superfluous. The networks are in a highly competitive race to attract people with Groups, Discussion Boards/Forums, Profiles and others that enable them to have more social interactions. Dunbar’s book shows that social networks get to the core of human behavior and survival.

- Social grooming is committing ourselves to others in certain situations by “stroking” them and letting them stroke us, usually in full view of others, who extend the scene via gossip. This releases endorphins. Grooming is so important that evolution has given us a little “kicker” to encourage the behavior.

- Social networks scale this incredibly; if you send someone an email thanking him/her, that is a one to one communication; however, if you thank him/her by writing on his/her Wall, all your Friends and his/her Friends see it, too. Depending on the intimacy of the thank you, it can be more valuable to write on the Wall.

- I also hope Dunbar’s work causes you to doubt that “social” behavior, especially on social networks, is inherently narcissistic, as many people have claimed. Of course, like other modes of behavior, it can be, but not necessarily.

- For more on social networks, groups and business strategy, see Geography 3.0: What It Is and What It Means.

Sociality, Trust and Productivity

- Grooming, Gossip.. shows that people use social interaction to determine how much and under what circumstances they can trust one another. When used correctly, social networks can lower the cost of trust.

- Dunbar’s and Rapaille’s work suggest that personal interactions get to trust far more quickly than “business” interactions. I’ll hazard that social topics can be a useful window into someone because people may be more off-guard when telling jokes than when having a business conversation. “Social” is serious business if you want people to feel comfortable with each other to trust each other enough to collaborate.

- Of course, gossip is all about politics, which Dunbar doesn’t cover in great detail. The gossiper is presenting the gossipee in a certain light, which may be quite distorted. It requires even more brain power to decipher and use the information gossip provides.

- Adam Christiansen shared an interesting IBM case study in which project team members who shared social information (i.e., family photos, cricket discussions, favorite music) with each other on Beehive (a digital social network) became productive close to twice as fast as control groups that didn’t share information.

- Grooming, Gossip.. shows why this is pervasively true with people in all cultures. When people are seemingly “goofing off” and gossiping, they are really learning where they stand with each other and other people. Huge implications for collaboration and productivity.

A New Look at Features in Social Networks

Social network platforms are designed to let us gossip and share social information about each other, and they break the mold here. Scaling social information will prove disruptive in every area of society. Grooming, Gossip.. provides the context for appreciating social networks’ transformational power.

- Profiles enable us to create a platform for our reputations in front of millions. We present ourselves as we want to be seen. Many platforms let other people gossip about us on our profiles (i.e. the Facebook Wall).

- Networks (of Friends, Connections…) are online and visible under certain conditions. They are explicit at an unprecedented level. Often, social information around the relationship is also viewable.

- Updates and Blogs allow us to manage our reputations, instant by instant. Twitter, Facebook, MySpace and LinkedIn enable others to contribute by writing on Walls, commenting on LinkedIn Status Visibility, retweeting, etc. Blogs enable tremendous interactivity about expressing and reporting about everything.

- Groups, in all social networks, enable us to create private and public groups for anything. Notably, they significantly reduce the cost of interacting around any topic.

- Photos and videos are rich media tools for sharing grooming, gestures, activities and moments. These are great tools for social grooming and, since they are scalable, they have tremendous promise.

Book Review: Decoding Evolutionary Roots of Human Social Behavior

By Christopher Rollyson

https://rollyson.net/book-review-grooming-gossip-and-the-evolution-of-language/

Grooming, Gossip and the Evolution of Language(1996), by Robin Dunbar

Robin Dunbar (born 1947) is a British anthropologist and evolutionary biologist specialising in primate behaviour.

His 1996 work Grooming, Gossip and the Evolution of Language pulls together his work on the social group sizes of various primates, including humans and the correlation with neocortex size relative to body mass. Although not intended as a work of popular science, the book’s style is very accessible and it may be read by non-specialists as well as academics.

The work appears to have been a considerable influence on the science-fiction novel Evolution, by Stephen Baxter.

The following is a chapter-by-chapter summary of this work:

Chapter 1. “Talking Heads”.

Describes the experience of being groomed by a monkey from the viewpoint of one of its peers: notes the similarities with the innuendoes and subtleties of everyday social experience of humans. The social life of humans, with its petty squabbles, joys and frustrations, is not unlike that of other primates. But there is one major difference – human language.

Curiously, when humans talk, most of the conversation is social tittle-tattle. Even in common-rooms of universities, etc, conversations about cultural, political, philosophical and scientific matters account for no more than a quarter of the conversation. The Sun devotes 78% of its copy to “human interest” stories and even the Times only devotes 57% to serious matters. Our much-vaunted capacity for language seems to be mainly used for exchanging information on social matters [anybody doubting Dunbar’s assertion needs look no further than Facebook]. Why should this be so?

Chapter 2. ”Into the Social Whirl”.

The answer may lie with our primate heritage. Monkeys and apes are highly sociable, their lives revolving around the small group of individuals with whom they live. They could not exist without their friends and relations.

Our ape ancestors faced disaster 10 million years ago as the climate became dryer and colder, causing their forest habitat to retreat. Monkeys became a nuisance, able to eat unripe fruit because their stomachs contain enzymes to neutralise the tannin that they contain that would give apes and humans an upset stomach. About 7 million years ago, one population of apes found itself forced out onto the savannahs bordering the forests. Mortality would have been desperately high but those that survived did so because they were able to exploit the new conditions.

All primates have had to deal with predators ranging from various felids, canids, monkey-eating eagles and even other primates. There are two main ways of dealing with primates. One is to be larger than any likely predator; the other is to live in a large group. The latter option reduces the risk in a number of ways: more eyes to detect a marauding predator; strength in numbers – a large group can drive off or even kill a predator; finally a large number of group-members fleeing in different directions will confuse a predator, often for long enough for all to get away.

But group living has disadvantages too. Social animals have to strike a balance between the dangers of predators and the problems of social tensions. The primate solution is for small groups to form coalitions within the larger overall living group. Such alliances take many forms, depending on the overall social and sexual dynamics of the species concerned. In all cases, however, grooming is the key to maintaining these alliances.

Primate alliances are built on the ability of animals to form inferences about the suitability and reliability of potential allies, but apes and monkeys can also practice deception and manipulative behaviour. They can do this because they can calculate the effect their actions are likely to have.

Chapter 3. “The Importance of Being Ernest”.

Grooming takes up a considerable amount of a monkey’s time, typically 10% though it can be as much as 20%. Grooming apparently releases endorphins, but while this encourages animals to groom it isn’t the evolutionary reason for it. One problem among social animals is “defection”, i.e. where one fails to return a favour. A solution is to make defection expensive, and grooming requires a considerable investment of time. Building alliances therefore requires commitment and it is therefore usually better to maintain existing relationships than try to build new ones.

In addition to grooming, monkeys use vocalisation to maintain their alliances. Monkeys make contact calls when moving through dense vegetation to enable the animals to keep track of one another. But subtle differences have been found in the utterances made by vervet monkeys depending on whether they are approaching a dominant animal or a subordinate one. Other calls were given when spotting another vervet group, or when moving out into open grassland. When these calls were recorded and played back, monkeys would look up when hearing calls from animals dominant over them, but ignore those from subordinates. Vervets also make a variety of predator warning calls which depend on the type of predator spotted. Other species use contact calls to keep in touch with preferred grooming partners.

But does any species, other than humans, have language? Attempts to teach apes to use language since the 1960s have produced unconvincing results, the oft-cited cases of Washoe, Kanzi etc notwithstanding. Human communications are on another level. What are they used for and why did they evolve?

Chapter 4. “Of Brains and Groups and Evolution”.

While bigger brains generally mean a smarter animal, the rule doesn’t always hold good because the size of the animal must also be taken into account. For example, whales and elephants have larger brains than humans, but they have to deal with a far greater muscle-mass than a human brain. When the relative brain-size is computed, it can be seen that the distributions for various groups of animals lie on different plains. Dinosaurs and fish lie below birds, which in turn lie below mammals. But among the mammals, there is also a hierarchy: marsupials lie at the bottom, followed by insectivores, then ungulates, then carnivores and finally at the top, primates. Here again there are levels: the prosimians at the bottom and the monkeys and apes at the top. The human brain is about nine times the size of the brain of a typical human-sized mammal and twelve times that of a human-sized insectivore [if such a species existed].

Why is this? It could not be due to chance, because of the high energy budget of a large brain, which is 20% of total in humans despite accounting for just 2% of total body mass. 1970s theories focussed on the need for greater problem-solving abilities; for example fruit eaters need bigger brains than herbivores, because supplies of fruit are harder to find.

Finding brightly-coloured fruit does require colour vision, which in turn requires more brain-power to process the input. Primates possess superior colour vision to other mammals [but so do birds and insects]. However this theory fails to explain why not all fruit eaters have large brains.

That social complexity might be linked to primate brain size was considered but not taken seriously until 1988, when British psychologists Dick Byrne and Andrew Whiten proposed what has become known as the Machiavellian Intelligence Hypothesis. This is based on the fact that monkeys and apes are able to use very sophisticated forms of social knowledge about each other. This knowledge about how others behave is used to predict how they might behave in the future and relationships are based upon these predictions.

The main problem with the theory was that many thought it was too nebulous to test. One problem for Dunbar was confounding factors: fruit eating primates require larger territories than leaf-eaters because the fruit is more widely-spaced. But many fruit-eaters such as baboons and chimpanzees are larger than leaf-eating monkeys and live in larger groups. There are four factors – body-size, brain-size, group-size and fruit-eating. The problem was to ensure that correlation between any two of these factors was not a consequence of both being correlated for quite distinct reasons with a third.

Dunbar decided to consider not the total brain size but the neocortex, which is the “thinking” part of the brain, where consciousness arises. The neocortex comprises the “grey matter” popularly associated with intelligence and it surrounds the deeper white matter in the cerebrum. In small mammals such as rodents it is smooth, but in primates and other larger mammals it has deep grooves (sulci) and wrinkles (gyri) which increase its surface area without greatly increasing its volume.

Dunbar then correlated the size of the neocortex against group size. He chose this as a measure of social complexity because of the volume of data available from field workers on many primate species and because it is a simple numerical value rather than a subjective assessment. Also group size is a measure of social complexity – the larger the group, the more relationships there are to keep track of. Dunbar found that there was a very good fit between the data and the ratio of neocortex volume to total brain volume. The findings provided support for the Machiavellian Intelligence Hypothesis – large brains were linked to the need to hold large groups together. Dunbar was also able to find the same the same correlation between neocortex ratio and group size in non-primate mammals such as vampire bats and some of the larger carnivores.

But just how does neocortex size relate to group size? There are possibilities beyond simply keeping track of social relationships. One is that the neocortex/group size correlation is more to do with quality rather than quantity of intra-group relationships. The Machiavellian hypothesis suggests that the key is the use primates make of their knowledge of others. There are two interpretations: firstly the relationship might be with the size of coalitions primates habitually remain rather than total group size, though larger coalitions are required in larger groups. The second is that primates need to be able to balance conflicting interests – playing one off against another, keeping as many happy as possible.

Research showed that primates form “grooming cliques”, with grooming occurring outside these groups being perfunctory and lacking enthusiasm; and distress calls from non-members likely to be ignored. Grooming seemed to be the glue that held coalitions together. When data about grooming clique size was combined with the data about group size and neocortex ratio, a good fit was found. As group size increases, so larger coalitions are required for mutual protection when living in these large groups.

Since humans are primates, it should be possible to predict group size for humans. The number turns out to be approximately 150 – Dunbar’s Number, as it is now known. Modern living – with millions living in cities – makes this prediction hard to test. However when considering hunter-gatherer societies – which is how we lived in pre-agricultural times, the largest grouping is a tribe, typically numbering 1500-2000 people who all speak the same language or dialect. Within tribes, smaller groupings known as clans can sometimes be discerned. Clan size – with very little variation – averages 150.

150 turns up elsewhere – early Neolithic villages typically had a population of around that number; religious communities such as the Hutterites and the Mormons lived in groups of 150; businesses can function informally with fewer than 150 employees, but require a formal management structure when the headcount exceeds this; army companies typically number around 150 men and so on.

The number of close friends and relatives people have tends to be around 11-12 with a fair degree of consistency. This corresponds to the “grooming clique” in primate societies, suggesting a neurological basis. Finally the maximum number of faces people can put a name has been found to be around 1500-2000 – suspiciously close to the size of a tribe in traditional societies.

Returning to grooming, a problem arises in that the larger primate group size is, the larger the grooming cliques need to be, and the more time needs to be devoted to grooming. Baboons and chimps have a group size of 50-55 individuals, and the amount of time they spend grooming is close to the upper limit of time that can be so spent without making inroads into the time needed to feed etc. If humans relied on grooming, then 40% of the day would have to be devoted to this activity.

The solution, Dunbar suggests, was language, which enabled several individuals to be “groomed” at once. When it comes to social networking, language has other advantages over grooming in that detailed information can be exchanged about individuals not actually present. Language is a “cheap and ultra-efficient form of grooming”. Dunbar rejects the conventional explanation of language evolving as a means to co-ordinate activities such as hunting more efficiently and suggests instead that it evolved primarily to allow humans to exchange social gossip.

Chapter 5. “The Ghost in the Machine”.

Language is for communication [contra Bickerton, 1990], somebody trying to influence the mind of another individual. We also consider implications of what people are saying, their body language, etc. We assume everybody behaves with conscious purpose and try to divine their intentions, often extending this to animals and even inanimate objects. Philosophers however doubted if consciousness existed outside of the human world.

Rene Descartes assumed that while humans had minds, animals – which lack language – did not and were nothing more than automatons. However in the second half of the 19th Century Darwin and his contemporaries began to reconsider the emotional and mental lives of animals. A view eventually emerged that since it was not possible to see into the minds of animals, studies should focus on their observable behaviour. The result was the psychological school known as “Behaviourism”, which held sway right up until the 1980s.

Since then, however, attention has switched to “Theory of Mind”. This means the ability to understand what another individual is thinking, to ascribe beliefs that might differ from one’s own and to believe that that individual does experience those beliefs as mental states. Furthermore ToM enables individuals to handle “orders of intentionality” or beliefs about what another believes; for example “I believe x” is first-order intentionality, “I believe that he believes X” is second-order and so on. Humans can at most handle six orders, as in the following sentence due to Dan Dennett:

“I suspect [1] that you wonder [2] whether I realise [3] how hard it is for you to be sure that you understand [4] whether I mean [5] to be saying that you can recognise [6] that I can believe [7] you want [8] me to explain that most of us can only keep track of five or six orders.”

In the 1980s it was discovered that children are not born with a theory of mind and that this does not develop until 4 – 4 ½ years old. Up until then they will fail the so-called “false belief test” which asks if the child is aware that somebody can hold a false belief. For example, the child is shown an object such as a doll or some sweets being put in a particular place in the presence of another individual called (say) Fred. Fred then leaves and the object is moved. Fred returns and the child is asked where they think Fred thinks the object is. Very young children fail the test by saying they think Fred thinks the object is in the new location. They cannot grasp that Fred doesn’t know the object has been moved and that he would assume it was still in its original location. Only older children, with ToM, pass this test. Autism is a failure to develop ToM.

Tests have been carried out on animals to see how their ToM compares with humans and to see if they have self-awareness. An early test was the mirror test, to see if an animal could recognise that a reflection of itself in a mirror was not another individual. Chimps can readily pass such tests, other great apes appear to be competent but gibbons and monkeys invariably fail, as do non-primates such as elephants and porpoises. The validity of this approach has been questioned, as animals do not encounter mirrors in the wild [though of course they might see their reflections in water].

“Tactical deception” is where one individual tries to exploit another by manipulating its knowledge of a situation. To practice tactical deception, an individual must have at least second-order intentionality. It appears to be virtually absent from the prosimians, rare in New World monkeys, but common among the socially-advanced Old World monkeys (baboons, macaques) and chimpanzees. The frequency with which species practiced tactical deception was found to show a good fit with relative neocortex size.

Dunbar reasoned that in species with a large relative neocortex size, low-ranking males should be able to use their brains to exploit loopholes in the system and mate with females, gain access to bananas, etc. Tests showed that this was the case; for example a low-ranking male would feign disinterest in a box containing a cache of bananas in the hope that a higher-ranking male who arrived on the scene shortly after would conclude that the box was locked.

Tests aimed at showing whether apes and monkeys have ToM have involved obtaining a food reward from a baited box and two human assistants, one of whom is not present when the bait is moved. The ape or monkey then had to choose which assistant they wanted to open a box. Chimps did reasonably well at the test, though less so than six-year-old children. This and other tests led researchers to conclude that chimps had limited theory of mind, but monkeys completely lacked it.

Chimps seem to be able to go to third-order intentionality on occasions, but humans can readily surpass this. Humans can envisage people and situations that do not exist in actuality – a prerequisite for producing literature. Humans are able to detach themselves from their immediate surroundings. Dunbar argues that this is a pre-requisite for both science and religion, though some of his colleagues object to the comparison! However both require one to question the world as we find it, which in turn requires third-order intentionality at minimum.

If fourth-order intentionality and above is required for science and religion, it is no mystery why only humans have these things. But if third-order intentionality will suffice, could apes not also have science and religion? It is conceivable, but the main problem is that apes lack language and so could not transmit their ideas to their peers.

Chapter 6. “Up through the Mists of Time”.

Five million years ago, one ape lineage seems to have made more use of the woodlands that lie beyond the edges of the shrinking forests. Animals travelling between the trees here are more exposed to the sun and Peter Wheeler has calculated that an animal walking upright under these conditions receive up to a third less heat from the sun, especially around the middle of the day. They also benefit from the slightly breezier conditions at heights above three feet. Also these upright apes could have shed body hair over the parts of their bodies not exposed to direct sunlight and improved cooling properties by sweating through the skin. A naked biped ape would expend half the amount of water on sweating compared with a furry quadruped ape.

Bipedalism begun fairly early in the hominid lineage, because “Lucy”, 3.3 my old, was already bipedal as inferred from the shape of the pelvis and the articulation of the knee and hip joints. The Laetoli footprints in Tanzania, 3.5 my old, were also made by bipeds. Quite likely these early hominids were naked although they were still more apes than humans.

In their new woodland habitat, these apes had to contend with greater predation, and in response they grew larger and increased their group size. While Lucy was a diminutive 4ft tall, the Narikitome Boy had reached a height of 5ft3 at age 11 and would have topped 6ft had he survived to adulthood. But how do we know their group size increased? The link with neocortex size offers a clue, and the link with grooming time might offer a clue as to when language evolved.

Archaeologists [in 1996] favoured a recent date of 50,000 years ago – the date of the [now abandoned] Upper Palaeolithic Revolution. Anatomists [even then] favoured a date of around 250,000 years ago, co-incident with the emergence of Homo sapiens. This was based on the fact that an asymmetry between the two halves of the brain could be detected at this point. In modern humans, the left hemisphere – where the language centres are located – is larger than the right. This, they argued, was evidence for the appearance of language.

To try to resolve the issue, Dunbar and Leslie Aiello tried to solve the group size issue and find the group size threshold that precipitated language. They reasoned it must lie somewhere between the 20% maximum grooming time for any existing primate and the predicted grooming time of 40% for humans, possibly 30%. They then discovered that in primates and carnivores [but obviously not elephants and whales], neocortex ratio is directly related to total brain size [I assume that means a linear relationship]. Given that estimates for cranial capacity were available for extinct hominids, it was possible to calculate the predicted group sizes. These remained within the ranges of existing apes at first, but rose above this with the appearance of genus Homo. 150 was reached 100,000 years ago, but by 250,000 years ago group sizes would already have reached 120-130, and grooming time would have hit a prohibitive 33-35%. But even 500,000 years ago, group sizes were at 115-120 with corresponding grooming times of 30-33%. [Rather confusingly, Dunbar then cites this time as coinciding with the emergence of Homo sapiens, having dated this event to 250,000 a short while previously. In 1996, humans from this far back were generally lumped together as archaic Homo sapiens; the term Homo heidelbergenis is now generally preferred.]

Homo erectus [then described as the predecessor to our own species] had a predicted group size of 100-120, with grooming time requirements of 25-30%. Dunbar and Aiello took the view that H. erectus lacked language. They also noted no drastic jump in grooming time at any point, which they take to mean that language emerged gradually over a long period of time.

As group sizes increased, so vocalisation began to supplement grooming; probably this process began two million years ago, with the emergence of Homo erectus. As time passed, so the meanings conveyed by the vocalizations increased, though the purpose would have remained largely social. Humans were exploiting the greater efficiency of language as a bonding mechanism to allow themselves to live in larger groups without increasing the amount of time required for social networking. Interestingly, modern hunter-gatherers spend around 3.5 hours for women and 2.7 hours for men on social interaction in a 12 hour day, or about 25%, compared to the 20% maximum observed for other primates.

On this view, the Neanderthals must also have possessed language. They did not become extinct for lack of language, but lacked the technological and cultural sophistication of the incoming Cro-Magnons. Later, the Native Americans and Australian Aborigines suffered the same fate [basically Dunbar is advancing an Upper Palaeolithic version of the Guns, Germs and Steel argument advanced by Jared Diamond (Diamond, 1997)].

What drove the increase in human group size? Baboons can get by with group sizes of 50, why can’t we, especially as we are larger and can carry defensive weapons? Indeed, hunter-gatherers typically live in temporary camps of around 30-35 individuals. Dunbar puts forward three possibilities:

Firstly, our forbears may have occupied more open habitats than those of baboons and needed greater protection. Gelada monkeys live in very open habitats with high risk of predation. They live in groups of 100-250 [so why don’t geladas have bigger brains than humans?].

The second possibility is that human groups were threatened by rival human groups, and bigger group sizes were needed to fend them off.

The third possibility is that following the emergence of Homo erectus, humans became nomadic and left Africa. In unknown territory, they would have had to wonder further to find resources and they would have encountered hostile residents determined to exclude them. This does occasionally happen with hamadryas baboons. Migrants are always at a disadvantage, but one solution is to establish reciprocal alliances with neighbouring groups. This happens with the !Kung San of the Kalahari, who live in communities of 100-200 individuals, but these are dispersed into smaller family-based groups of 25-40. This is known as a fission-fusion system, because members are constantly coming and going. The same characteristic is seen with chimpanzees – the primary community is around 55, but foraging parties often only occupy 3-5 individuals. That we share this characteristic with chimpanzees suggests it emerged very early in our history.

Dunbar opts for this third theory.

The theory that language emerged to facilitate social bonding should be testable. Investigating conversations in various informal situations, Dunbar and his students discovered that conversation groups did not typically exceed four. Conversation groups start when two or three people start talking. Others join in, but once the number of participants rises above four it is difficult to hold everybody’s attention and the group tends to fissions as two distinct conversations start. At any one time, only one person will normally be speaking and the others will be listening, just as at any one time only one ape or monkey will be doing the grooming. If the speaker corresponds to the “groomer” then they are “grooming” up to three others rather than only one, meaning group size could potentially treble. The group size of 55 for chimps and baboons becomes very close to the “Dunbar Number” of 150.

The limit of four people in a conversation group arises from the distance apart people must stand if they form a circle. Once the diameter of the circle increases beyond a certain point, it is not possible for everybody to hear everybody else clearly without shouting, assuming normal background noise levels. The critical distance turns out to be two feet, and it is difficult for more than four people to all remain within this distance of each other.

The researchers also learned that as per Dunbar’s predictions, 60-70% of the conversations concerned social topics. Politics, religion, work etc took up no more than 2-3% and even sport and leisure topics accounted for barely 10%.

Taken together, this data supports Dunbar’s theory that language evolved primarily to facilitate social bonding.

The expensive tissue hypothesis is based on the enormous energy costs of running a brain, which in humans takes up 20% percent of the total energy budget. But total energy production of mammals is a function of size and humans generate no more energy than any other mammal of that size, despite having a brain nine times larger than a typical human-sized mammal. Where does the energy to run the brain come from? Clearly it must come from savings elsewhere [unlike governments, humans have to balance the books]. In addition to the brain, the biggest energy consumers are the heart, kidneys, liver and gut – indeed these use up between them 85-90% of the body’s energy budget. The heart, kidneys and liver cannot be downsized, which leaves only the gut. With a smaller, less-efficient gut, humans have to eat high energy easy to assimilate foods. Meat is one such food, and the shift from the predominantly vegetarian diet of the australopithecines to one with higher meat content seems to have corresponded to the initial increase in brain size. Initially this would have come from scavenging, but the second phase of brain expansion, 500,000 years ago seems to correspond to the beginnings of organized hunting. Aiello and Wheeler believe that big brains only became possible with a switch to meat eating.

But big brains had another cost – the problem of getting a large brained infant down the narrow birth canal. The problem was solved by what is in effect premature birth, with a huge investment required by the parents in post-natal care. Women couldn’t do it all on their own; men had to do their bit. The tendency to male-female pair bonding was the result. Sexual dimorphism, considerable in even australopithecines, reduced. Differences in canine teeth, pronounced in cases of sexual dimorphism, almost vanished. Human males are only slightly larger than females. The implications are a shift from a strongly polygamous mating system to one that is only mildly so. Harem groups became smaller, with males having to make do with two females, and many having to get by with just the one! Provisioning more than one female would also have been expensive [a trend that has continued to the present day].

Chapter 7. “The First Words”.

There are three competing theories for the origins of language. The first states that the earliest languages were gesture-based; the second that it arose from monkey-like vocalizations; and the third is that it arose from music.

The gestural theory arises from the fact that fine motor control used for speech and aimed throwing is generally located in the left hemisphere of the brain. In addition to fine motor control, precise control of breathing is required and for this it was necessary for the monkey’s dog-like chest to change to the flattened chest characteristic of apes. When the body’s weight is on the arms, it restricts the chests ability to expand and contract and monkeys can only breathe once with each stride.

When apes adopted a climbing lifestyle, the monkey rib-cage was a major problem. In monkeys, the shoulder blades prevent the arms swinging in a circle, which prevents them from reaching above their heads while climbing. Eventually the scapula moved round to the back of the ribcage and arm-joints became positioned on the outer edge of the chest. The flattened rib cage of the apes was the result, which had the additional benefit of freeing the constraints on breathing.

The anatomical changed permitted aimed throwing. Chimps could out-throw Olympic athletes, but their accuracy is poor because they lack the fine motor control of humans. But our fine motor control, so the theory goes, could also be used to control speech.

The problems with this theory are language involves conceptual thinking, which is quite different to aimed throwing; the complexity possible with gestures is limited; and gestures require people to be in visual contact. Communication would be impossible after dark, when one might have expected a lot of social gossip to take place.

But why did fine motor control evolve in the left hemisphere? Dunbar suggests it is because the right hemisphere was already fully utilised processing emotional information. He speculates the speech evolved in the left hemisphere because there was room there, and fine motor control evolved there later – either for the same reason or because the left side is associated with conscious thought, which is required for aimed throwing. This is the reverse of the sequence of events required by the gesture theory. The reason the majority of us are right-handed is because sensory and motor control nerves from one side of the body cross over to the other side of the brain; the left hemisphere controls the right hand side of the body, and vice-versa.

There is a greater sensitivity to visual cues on the left hand side of the visual field. This lateralization seems to have appeared very early on and fossil trilobites tend to have more scars on the right side, suggesting pursuing predators attached more frequently from the left hand side.

Lateralization of language in the left hemisphere meant that this side became the seat of consciousness, where as emotional behaviour was seated in the right hemisphere [as Dunbar points out, this was the basis of Julian Jaynes’ theory about “bicameral minds” (Jaynes, 1976)].

It turns out that music and poetry are located in the right side. This also suggests that the theory of a musical origin for language cannot be correct.

Dunbar turns to the vocalizations of monkeys as the origins of language [a conclusion that Bickerton (1990) rejects]. He considers the predator-specific calls of vervets and also conversational patterns of gelada monkeys. The calls of these animals appear to be timed in anticipation of others rather than in simple response, just as human conversation is carried on by one individual anticipating the end of the speaker’s phrase or sentence rather than simply waiting for them to stop speaking. The vervet’s calls are an archetypal proto-language in which arbitrary sounds can be used to refer to specific objects, and overtones can be applied to increase the information content. Formalizing sound patterns to carry more information is but a small step; language is but a further small step [though Bickerton would disagree].

If it is accepted that the beginnings of language were the vocalizations of primates, there are still alternative views on the next step. One theory is that language arose out of song-and-dance rituals designed to co-ordinate the emotional states of group members [c.f. Mithen, 2006]. While Dunbar believes language arose to exchange social gossip, he considers this alternative viewpoint.

No society lacks song-and-dance, which on the face of it odd. Much has parallels with bird-song, which is used to defend territory or advertise for a mate. Maasai warriors, Maoris, All Blacks and Scots Guards use ritual song and dance (the Haka, bagpipes, etc) before going into battle. But song is also used in churches and bars in circumstances not associated with battle. Here Dunbar considers the “crowd effect” which leads to groups of people being amenable to far more extreme and intolerant views than individuals. Psychologists identified this phenomenon in the 1960s and referred to it as a “risky shift”. It led to the Crusades, Northern Ireland, Rwanda and Yugoslavia [the Nazis were of course consciously exploiting the phenomenon back in the 1930s at Nuremberg, though Dunbar does not mention this].

Dunbar believes that the explanation is that song and dance is an expensive activity. Deep bass tones are particularly difficult to produce. They are associated with a large and powerful body. Even among humans, there is a tendency to assume powerful, successful people to be tall. In every US presidential election since the war, the taller candidate has won. [The sequence was broken in 2000, when George W Bush (6ft) defeated Al Gore (6ft1) and subsequently held off the challenge of an even taller man, John Kerry (6ft4), in 2004. However in 2008 the taller candidate won when Barack Obama (6ft2) defeated John McCain (5ft9).] People often comment on how small the Queen is [she was positively dwarfed by Michelle Obama (5ft11)]. There is no doubt that smaller people have to work harder to get to the top and have to be fairly bloody-minded. But, as Napoleon and others have shown, it certainly can be done.

It does however appear to be almost universal that deep voices are needed to create a lasting impression. The peculiar deep voice associated with Margaret Thatcher is about half an octave below her natural voice. Thatcher’s advisers encouraged her to lower her voice after she became Tory leader in 1975.

Trying to hold together a group of 150 people is difficult even now and it must have been even harder 250,000 years ago in the woodlands of Africa. Song and dance would have had a role to play. The activity would have stimulated endorphin production. Chris Knight believes that the use of ritual to coordinate human groups by synchronising emotional states is a very ancient feature of human behaviour, coinciding with the rise of human culture and language. Ritual language would have been required to co-ordinate such activities, and this may have been the final stimulus for the evolution of language [I have to say I’m dubious; such organized rituals would surely have required the participants to already be behaviourally modern]. Dunbar is unconvinced and believes this use for language only came later. He believes song-and-dance may well have preceded language, but it was at first informal, unstructured and spontaneous, like chanting at football matches. [This probably explains why attempts by clubs and fan groups to orchestrate the atmosphere at football clubs with schemes such as “singing sections” invariably fail; also fans tend to devote at least as much time to chants abusing the referee or rival teams as they do to songs encouraging their own side.]