Gerrymandering - the political manipulation of electoral district boundaries with the intent to create undue advantage for a party, group, or socioeconomic class within the constituency.

Gerrymandering's primary goals are to maximize the effect of supporters' votes and minimize the effect of opponents' votes. A partisan gerrymander's main purpose is to influence not only the districting statute but the entire corpus of legislative decisions enacted in its path.

These can be accomplished in a number of ways:

- Cracking: involves spreading voters of a particular type among many districts in order to deny them a sufficiently large voting bloc in any particular district. Political parties in charge of redrawing district lines may create more "cracked" districts as a means of retaining, and possibly even expanding, their legislative power. By "cracking" districts, a political party can maintain, or gain, legislative control by ensuring that the opposing party's voters are not the majority in specific districts.[22][23] For example, the voters in an urban area can be split among several districts in each of which the majority of voters are suburban, on the presumption that the two groups would vote differently, and the suburban voters would be far more likely to get their way in the elections.

- Packing: is concentrating many voters of one type into a single electoral district to reduce their influence in other districts. In some cases, this may be done to obtain representation for a community of common interest (such as to create a majority-minority district), rather than to dilute that interest over several districts to a point of ineffectiveness (and, when minority groups are involved, to avoid lawsuits charging racial discrimination). When the party controlling the districting process has a statewide majority, packing is usually not necessary to attain partisan advantage; the minority party can generally be "cracked" everywhere. Packing is therefore more likely to be used for partisan advantage when the party controlling the districting process has a statewide minority, because by forfeiting a few districts packed with the opposition, cracking can be used in forming the remaining ones.

- Hijacking: redraws two districts in such a way as to force two incumbents to run against each other in one district, ensuring that one of them will be eliminated.

- Kidnapping: moves an incumbent's home address into another district. Reelection can become more difficult when the incumbent no longer resides in the district or faces reelection in a new district with a new voter base. This is often employed against politicians who represent multiple urban areas: larger cities are removed from the district to make it more rural.

These tactics are typically combined in some form, creating a few "forfeit" seats for packed voters of one type in order to secure more seats and greater representation for voters of another type. This results in candidates of one party (the one responsible for the gerrymandering) winning by small majorities in most of the districts, and another party winning by a large majority in only a few. Any party that endeavors to make a district more favorable to voting for it based on the physical boundary is gerrymandering.

Wayne Dawkins describes it as politicians picking their voters instead of voters picking their politicians.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gerrymandering

Me - ChatGPT can you create a list of gerrymandering methods?

ChatGPT - Sure, here's the list of gerrymandering methods:

- Packing: This involves drawing district boundaries to concentrate voters of a particular group or party into a smaller number of districts, in order to minimize their influence in other districts.

- Cracking: This is where district boundaries are redrawn to split a group of voters that typically vote for the same party or candidate, diluting their voting power across multiple districts and making it more difficult for them to win in any of them.

- Kidnapping or hijacking: This involves redrawing the district boundaries to force two incumbent politicians to run against each other in the same district, thereby eliminating one of them from the race.

- Incumbent protection: This is where district boundaries are redrawn to protect incumbents from a potential challenger by diluting the opposition party's voting strength in the district.

- Stealth gerrymandering: This method involves redrawing district boundaries in a way that is not immediately obvious, such as using subtle geographic features like rivers or highways to divide communities.

- Absentee gerrymandering: This involves manipulating absentee voting rules or locations to benefit one party or group over another.

It's important to note that these methods are not mutually exclusive, and gerrymandering often involves a combination of tactics to achieve the desired outcome. Ultimately, gerrymandering undermines the principles of democratic representation and can result in unfair and unrepresentative election outcomes.

Text generated by ChatGPT, try free here; http://openai.com/

New poll: Everybody Hates Gerrymandering

Gerrymandering graphic from this Fairvote article

https://www.fairvote.org/new_poll_everybody_hates_gerrymandering

After the Census Bureau releases detailed population and demographic data from the 2020 census on August 12, states and local governments begin the once-a-decade process of drawing new voting district boundaries known as redistricting. And gerrymandering — when those boundaries are drawn with the intention of influencing who gets elected — is bound to follow.

The current redistricting cycle will be the first since the Supreme Court’s 2019 ruling that gerrymandering for party advantage cannot be challenged in federal court, which has set the stage for perhaps the most ominous round of map drawing in the country’s history.

Here are six things to know about partisan gerrymandering and how it impacts our democracy.

Gerrymandering is deeply undemocratic.

Every 10 years, states redraw their legislative and congressional district lines following the census. Because communities change, redistricting is critical to our democracy: maps must be redrawn to ensure that districts are equally populated, comply with laws such as the Voting Rights Act, and are otherwise representative of a state’s population. Done right, redistricting is a chance to create maps that, in the words of John Adams, are an “exact portrait, a miniature” of the people as a whole.

But sometimes the process is used to draw maps that put a thumb on the scale to manufacture election outcomes that are detached from the preferences of voters. Rather than voters choosing their representatives, gerrymandering empowers politicians to choose their voters. This tends to occur especially when linedrawing is left to legislatures and one political party controls the process, as has become increasingly common. When that happens, partisan concerns almost invariably take precedence over all else. That produces maps where electoral results are virtually guaranteed even in years where the party drawing maps has a bad year.

There are multiple ways to gerrymander.

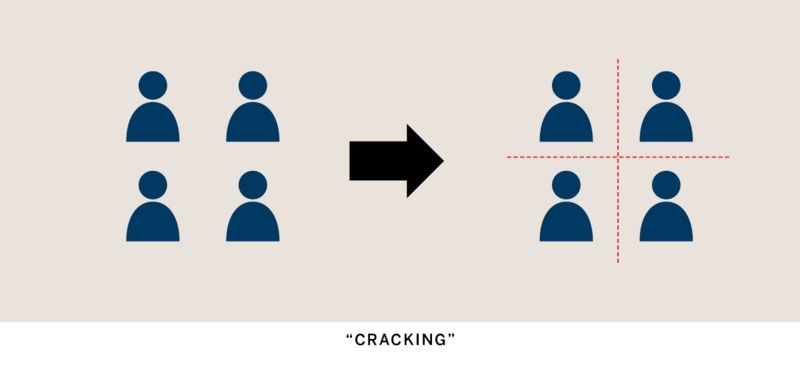

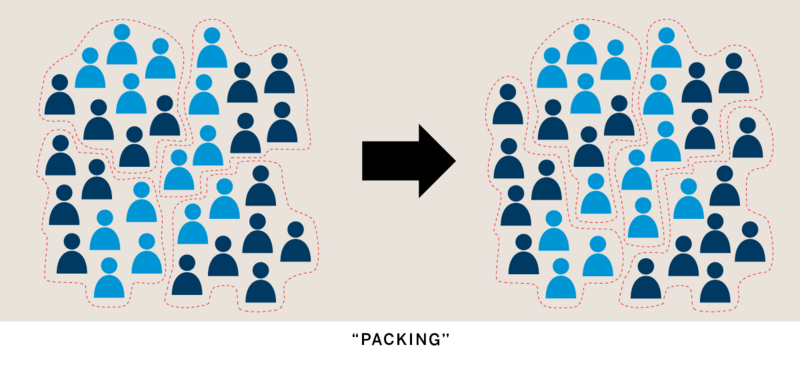

While legislative and congressional district shapes may look wildly different from state to state, most attempts to gerrymander can best be understood through the lens of two basic techniques: cracking and packing.

Cracking splits groups of people with similar characteristics, such as voters of the same party affiliation, across multiple districts. With their voting strength divided, these groups struggle to elect their preferred candidates in any of the districts.

Packing is the opposite of cracking: map drawers cram certain groups of voters into as few districts as possible. In these few districts, the “packed” groups are likely to elect their preferred candidates, but the groups’ voting strength is weakened everywhere else.

Some or all of these techniques may be deployed by map drawers in order to build a partisan advantage into the boundaries of districts. A key note, however: while sometimes gerrymandering results in oddly shaped districts, that isn’t always the case. Cracking and packing can often result in regularly shaped districts that look appealing to the eye but nonetheless skew heavily in favor of one party.

Gerrymandering has a real impact on the balance of power in Congress and many state legislatures.

In 2010, Republicans — in an effort to control the drawing of congressional maps — forged a campaign to win majorities in as many state legislatures as possible. It was wildly successful, giving them control over the drawing of 213 congressional districts. The redrawing of maps that followed produced some of the most extreme gerrymanders in history. In battleground Pennsylvania, for example, the congressional map gave Republicans a virtual lock on 13 of the state’s 18 congressional districts, even in elections where Democrats won the majority of the statewide congressional vote.

Nationally, extreme partisan bias in congressional maps gave Republicans a net 16 to 17 seat advantage for most of last decade. Michigan, North Carolina, and Pennsylvania alone — the three states with the worst gerrymanders in the last redistricting cycle — accounted for 7 to 10 extra Republican seats in the House.

On the state level, gerrymandering has also led to significant partisan bias in maps. For example, in 2018, Democrats in Wisconsin won every statewide office and a majority of the statewide vote, but thanks to gerrymandering, won only 36 of the 99 seats in the state assembly.

Though Republicans were the primary beneficiaries of gerrymandering last decade, Democrats have also used redistricting for partisan ends: in Maryland, for instance, Democrats used control over map-drawing to eliminate one of the state’s Republican congressional districts.

Regardless of which party is responsible for gerrymandering, it is ultimately the public who loses out. Rigged maps make elections less competitive, in turn making even more Americans feel like their votes don’t matter.

Gerrymandering affects all Americans, but its most significant costs are borne by communities of color.

Residential segregation and racially polarized voting patterns, especially in southern states, mean that targeting communities of color can be an effective tool for creating advantages for the party that controls redistricting. This is true regardless of whether it is Democrats or Republicans drawing the maps.

The Supreme Court’s 2019 decision in Rucho v. Common Cause greenlighting partisan gerrymandering has made things worse. The Voting Rights Act and the Constitution prohibit racial discrimination in redistricting. But because there often is correlation between party preference and race, Rucho opens the door for Republican-controlled states to defend racially discriminatory maps on grounds that they were permissibly discriminating against Democrats rather than impermissibly discriminating against Black, Latino, or Asian voters.

Targeting the political power of communities of color is also often a key element of partisan gerrymandering. This is especially the case in the South, where white Democrats are a comparatively small part of the electorate and often live, problematically from the standpoint of a gerrymanderer, very close to white Republicans. Even with slicing and dicing, discriminating against white Democrats only moves the political dial so much. Because of residential segregation, it is much easier for map drawers to pack or crack communities of color to achieve maximum political advantage.

Gerrymandering is getting worse.

Gerrymandering is a political tactic nearly as old as the United States. In designing Virginia’s very first congressional map, Patrick Henry attempted to draw district boundaries that would block his rival, James Madison, from winning a seat. But gerrymandering has also changed dramatically since the founding: today, intricate computer algorithms and sophisticated data about voters allow map drawers to game redistricting on a massive scale with surgical precision. Where gerrymanderers once had to pick from a few maps drawn by hand, they now can create and pick from thousands of computer-generated maps.

Gerrymandering also looks likely to get worse because the legal framework governing redistricting has not kept up with demographic changes. Before, most people of color in the country’s metro areas lived in highly segregated cities. Today, however, a majority of Black, Latino, and Asian Americans live in diverse suburbs. This change has given rise to powerful new multiracial voting coalitions outside cities such as Atlanta, Dallas, and Houston that have won or come close to winning power. Yet the Supreme Court has not granted these multiracial coalition districts the same legal protections as majority-minority districts, making them a key target for dismantling by partisan map drawers.

Federal reform can help counter gerrymandering — but Congress needs to act soon.

The For the People Act, a landmark piece of federal democracy reform legislation that has already passed the House, represents a major step toward curbing political gamesmanship in map drawing. The bill would enhance transparency, strengthen protections for communities of color, and ban partisan gerrymandering in congressional redistricting. It would also improve voters’ ability to challenge gerrymandered maps in court.

With redistricting now beginning in many states, the need for Congress to pass reform legislation is more urgent than ever. Unless that happens, we risk another decade of racially and politically discriminatory line-drawing. But time is running short. The Census Bureau released data to the states for redistricting on August 12. If new laws are to have the maximum impact, Congress needs to act quickly. Fair representation depends on it.

https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/research-reports/gerrymandering-explained

Gerrymandering | Definition, Litigation, & Facts

Gerrymandering, in U.S. politics, the practice of drawing the boundaries of electoral districts in a way that gives one political party an unfair advantage over its rivals (political or partisan gerrymandering) or that dilutes the voting power of members of ethnic or linguistic minority groups (racial gerrymandering). The term is derived from the name of Gov. Elbridge Gerry of Massachusetts, whose administration enacted a law in 1812 defining new state senatorial districts. The law consolidated the Federalist Party vote in a few districts and thus gave disproportionate representation to Democratic-Republicans. The outline of one of these districts was thought to resemble a salamander. A satirical cartoon by Elkanah Tisdale that appeared in the Boston Gazette graphically transformed the districts into a fabulous animal, “The Gerry-mander,” fixing the term in the popular imagination.

A basic objection to gerrymandering of any kind is that it tends to violate two tenets of electoral apportionment—compactness and equality of size of constituencies. The constitutional significance of the latter principle was set forth in a U.S. Supreme Court ruling issued in 1962, Baker v. Carr, in which the Court held that the failure of the legislature of Tennessee to reapportion state legislative districts to take into account significant changes in district populations had effectively reduced the weight of votes cast in more populous districts, amounting to a violation of the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. In 1963, in Gray v. Sanders, the Court first articulated the principle of “one person, one vote” in striking down Georgia’s county-based system for counting votes in Democratic primary elections for the office of U.S. senator. One year later, in Wesberry v. Sanders, the Court declared that congressional electoral districts must be drawn in such a way that, “as nearly as is practicable, one man’s vote in a congressional election is to be worth as much as another’s.” And in the same year, the Court affirmed, in Reynolds v. Sims, that “the Equal Protection Clause requires that the seats in both houses of a bicameral state legislature must be apportioned on a population basis.”

Regarding cases of gerrymandering based on race, the Supreme Court has held (in Thornburg v. Gingles, 1986) that such practices are incompatible with Section 2 of the 1965 Voting Rights Act (as amended in 1982), which generally prohibits voting standards or practices whose practical effect is that members of racial minority groups “have less opportunity than other members of the electorate to…elect representatives of their choice.” In Shaw v. Reno (1993), the Court ruled that electoral districts whose boundaries cannot be explained except on the basis of race can be challenged as potential violations of the equal protection clause, and in Miller v. Johnson (1995) it held that the equal protection clause also prohibits the use of race as the “predominant factor” in drawing electoral-district boundaries.

Until the 1980s, disputes regarding political gerrymandering were generally considered nonjusticiable (not decidable by federal courts) on the presumption that they presented “political questions” that are properly decided by the legislative or the executive branch. In Davis v. Bandemer (1986), however, a plurality of the Supreme Court held that political gerrymanders could be found unconstitutional (under the equal protection clause) if the resulting electoral system “is arranged in a manner that will consistently degrade a voter’s or a group of voters’ influence in the political process as a whole.” A majority of the Court also agreed that the instance of gerrymandering before it did not display any of the “identifying characteristics of a nonjusticiable political question” that had been laid out in Baker v. Carr, including, as the Baker Court had put it, “a lack of judicially discoverable and manageable standards for resolving it.” Although the majority in Bandemer could not agree on what standards should be used to adjudicate challenges to political gerrymanders, it refused to accept that none existed, declaring on that basis that “we decline to hold that such claims are never justiciable.”

In 2004, in Vieth v. Jubelirer, a plurality of the Court pointedly embraced what the Bandemer Court had declined to hold, on the grounds that “no judicially discernible and manageable standards for adjudicating political gerrymandering claims have emerged” since the Bandemer decision. Although siding with the plurality in rejecting the challenge to the political gerrymander in question, Justice Anthony Kennedy asserted that it had not been long enough since the Bandemer decision to conclude that no suitable standards could ever emerge (“by the timeline of the law 18 years is rather a short period”). Pointing to the rapid development and routine use of computer-assisted districting, he argued that such technologies “may produce new methods of analysis that…would facilitate court efforts to identify and remedy the burdens” imposed by political gerrymanders, “with judicial intervention limited by the derived standards.”

Just such a standard was proposed in Gill v. Whitford (2018), a challenge to a Wisconsin redistricting law enacted by the Republican-controlled state legislature following the 2010 decennial census. In that case, the plaintiffs argued that the discriminatory effects of the redistricting plan could be measured objectively by comparing the “efficiency” of votes cast for Republican or Democratic candidates in state legislative elections since 2012. Political gerrymandering characteristically results in a greater number of “wasted” votes for the disfavoured party (i.e., votes for a losing candidate or votes for a winning candidate in excess of the number needed to win), a discrepancy that can be represented as an “efficiency gap” between the parties when the difference between wasted votes is divided by the total number of votes cast. The plaintiffs argued that efficiency gaps of 7 percent or greater were legally significant because they were more likely than smaller gaps to persist through the 10-year life of a redistricting plan. The Court’s ruling, however, did not consider whether the efficiency gap amounted to the “judicially discernible and manageable” standard it had been waiting for. Instead, the justices held unanimously (9–0) that the plaintiffs lacked standing to sue, and the case was remanded (7–2) to the district court for further argument.

Following Kennedy’s retirement in 2018, the Supreme Court once again took up the issue of the justiciability of political gerrymandering claims in Rucho v. Common Cause (2019). There the Court’s conservative majority, over the bitter objections of its more liberal members, declared (5–4) that “partisan gerrymandering claims present political questions beyond the reach of the federal courts.” Extreme gerrymandering is also an issue in the ongoing case Moore v. Harper, argued before the Supreme Court in December 2022.

Brian Duignan The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica

https://www.britannica.com/topic/gerrymandering