Behavioral Modernity is a suite of behavioral and cognitive traits that distinguishes current Homo sapiens from other anatomically modern humans, hominins, and primates. Most scholars agree that modern human behavior can be characterized by abstract thinking, planning depth, symbolic behavior (e.g., art, ornamentation), music and dance, exploitation of large game, and blade technology, among others. Underlying these behaviors and technological innovations are cognitive and cultural foundations that have been documented experimentally and ethnographically by evolutionary and cultural anthropologists. These human universal patterns include cumulative cultural adaptation, social norms, language, and extensive help and cooperation beyond close kin.

Within the tradition of evolutionary anthropology and related disciplines, it has been argued that the development of these modern behavioral traits, in combination with the climatic conditions of the Last Glacial Period and Last Glacial Maximum causing population bottlenecks, contributed to the evolutionary success of Homo sapiens worldwide relative to Neanderthals, Denisovans, and other archaic humans.

Arising from differences in the archaeological record, debate continues as to whether anatomically modern humans were behaviorally modern as well. There are many theories on the evolution of behavioral modernity. These generally fall into two camps: gradualist and cognitive approaches. The Later Upper Paleolithic Model theorises that modern human behavior arose through cognitive, genetic changes in Africa abruptly around 40,000–50,000 years ago around the time of the Out-of-Africa migration, prompting the movement of modern humans out of Africa and across the world.

Other models focus on how modern human behavior may have arisen through gradual steps, with the archaeological signatures of such behavior appearing only through demographic or subsistence-based changes. Many cite evidence of behavioral modernity earlier (by at least about 150,000–75,000 years ago and possibly earlier) namely in the African Middle Stone Age. Sally McBrearty and Alison S. Brooks are notable proponents of gradualism, challenging European-centric models by situating more change in the Middle Stone Age of African pre-history, though this version of the story is more difficult to develop in concrete terms due to a thinning fossil record as one goes further back in time.

To classify what should be included in modern human behavior, it is necessary to define behaviors that are universal among living human groups. Some examples of these human universals are abstract thought, planning, trade, cooperative labor, body decoration, and the control and use of fire. Along with these traits, humans possess much reliance on social learning. This cumulative cultural change or cultural "ratchet" separates human culture from social learning in animals. As well, a reliance on social learning may be responsible in part for humans' rapid adaptation to many environments outside of Africa. Since cultural universals are found in all cultures including some of the most isolated indigenous groups, these traits must have evolved or have been invented in Africa prior to the exodus.

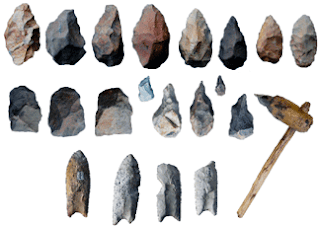

Archaeologically, a number of empirical traits have been used as indicators of modern human behavior. While these are often debated[18] a few are generally agreed upon. Archaeological evidence of behavioral modernity includes:

- Burial

- Fishing

- Figurative art (cave paintings, petroglyphs, dendroglyphs, figurines)

- Systematic use of pigment (such as ochre) and jewelry for decoration or self-ornamentation

- Using bone material for tools

- Transport of resources over long distances

- Blade technology

- Diversity, standardization, and regionally distinct artifacts

- Hearths

- Composite tools

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Behavioral_modernity

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Middle_Paleolithic#Origin_of_behavioral_modernity

The Transition to Modern Behavior

Modern behavior can be recognized by creative and innovative culture, language, art, religious beliefs, and complex technologies (d'Errico & Stringer 2011). One of the evolved capabilities underlying modern behavior is the ability to communicate habitually and effortlessly in symbols. The pervasiveness of symbolism in present-day human culture is the reason why archaeologists frequently search for artifacts that reflect ‘symbolically mediated behavior' (Henshilwood & Marean 2003). Modern behavior also consists of other components such as advanced problem solving and long range planning abilities (Wynn & Coolidge 2011). Archaeological artifacts that were produced by thinking ahead of future actions, anticipating problems and preparing responses provide evidence for modern planning abilities (Wadley 2010).

Traces of 'Modern Behavior' in the Archaeological Record

Modern behavior has, for example, been inferred from certain traits in the archaeological record. These traits include standardization in artifact types, blade technology, worked bone and other organic materials, personal ornaments and art or images, structured living spaces, ritual, economic intensification, enlarged geographic ranges and expanded exchange networks (McBrearty & Brooks 2000). The relatively sudden appearance of such traits as a group or package in the archaeological record of the European Upper Palaeolithic has been interpreted as evidence for the onset of modern behavior (Klein 2008).

When the standard of symbolism is applied, it can be shown that artifacts of a clearly symbolic nature appear only after 100,000 years ago (Henshilwood et al. 2002, Henshilwood et al. 2004, d'Errico et al. 2009, Texier et al. 2010). These artifacts include beads as well as ochre and ostrich eggshell with geometrically engraved patterns.

The evolution of modern planning capabilities can be investigated by analyzing the decision steps used to produce ancient tools. There are, for example, many different ways of making stone artifacts. Over the last 200,000 years a variety of reduction techniques in different combinations were used to make stone tools. This resulted in different techno-complexes, but all with the same degree of complexity. This may mean that humans had essentially modern cognitive capabilities for this period of time (Shea 2011). Using variability in stone tools as a marker has the advantage of including the most ubiquitous and widely studied type of material culture in the archaeological record in the search for modern behavior (Nowell & Davidson 2010). Advanced planning abilities were necessary to produce some ancient hunting weapons. For at least the past 200,000 years hunting implements were made by mounting sharp stone tools on a shaft with the aid of adhesives. The backed artefacts from the Howiesons Poort, dating to around 65,000 years ago in South Africa, are examples of such hafted stone tools.

Microscopic analysis of Howiesons Poort backed tools from Sibudu Cave in KwaZulu Natal, South Africa, revealed hafting microtraces associated with microresidues of ochre and acacia gum (Lombard 2008). Lyn Wadley and her team experimentally produced adhesives using these materials, and tested how to haft stone tools to shafts. They found that several ingredients, including ochre, plant gum, and fatty substances were combined to produce the compound adhesive. In addition, several procedures and complicated use of fire, or pyrotechnology, had to be manipulated to achieve the appropriate consistency for an adhesive that would successfully join the tool to the haft when thrown. The cognitive strategy used to produce and manipulate the adhesive in the Howiesons Poort 65,000 years ago indicates multitasking and planning capabilities typical of modern people (Wadley et al. 2009, Wadley 2010).

The Transition to Modern Behavior | Learn Science at Scitable

https://www.nature.com/scitable/knowledge/library/the-transition-to-modern-behavior-86614339/

On one view, behavioural modernity is a cluster of cognitive capacities that are both critical in themselves to contemporary human culture and which leave a detectable signature in the historical record. Perhaps, the most influential paper in this genre is Sally McBrearty and Andrew Brooks' The Revolution That Wasn't. As the authors see it, these cognitive competences are: behavioural and technological innovativeness; abstract thinking (the capacity to think about the elsewhere and the elsewhen); the ability to plan as an individual and to coordinate with others; and the ability to make and use physical symbols. And they suggest potential archaeological signatures of all of these capacities. The most obvious are technological signatures of innovation. Innovation is signalled by any or all of: new stone technologies (blades, microblades, backing); the increasing use of new materials like bone and antler; a larger toolkit (e.g. projectiles); and an increased control of fire. Likewise, they argue that planning and coordination can be detected in the historical record, for example, in the expansion of the human range into challenging environments. Moreover, the capacity to hunt large and dangerous animals without excessive risk is the evidence of planning, cooperation and coordination, and not just of technological ability. Symbolic behaviour, too, they argue, leaves a detectable signature. The most obvious is self-adornment with beads and ornaments, but it is also evident in the use of pigment, in decorated objects, in burying the dead and in the imposition of style on utilitarian objects.

From hominins to humans: how sapiens became behaviourally modern

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3048993/

Middle Paleolithic sites…

- blade and bladelet technology;

- microlithic technology;

- the first portable art, comprising figurines of women (Venuses) and animals;

- the first parietal (or wall) art, consisting of paintings and engravings in caves (Cook 2013);

- the earliest bone, ivory, and antler tools;

- ochre or other pigment processing;

- specialization in hunting one or two species of animals;

- the use of fish or shellfish;

- more complex burials;

- long-distance exchange of raw materials and finished items;

- the first information networks and emergence of ethnic groups; and

- the spread of people into new regions, such as Siberia, the Americas, and Australia.

Based on worldwide hunter-gatherer ethnographic data, Binford (1980) also argued that only modern people could organize themselves using a collector strategy of mobility, where one brings resources to people. As a result, people could be permanently settled year-round in the same community, which is the opposite of what he called the forager strategy, where people moved seasonally to resources (Binford 1980, 1989). Thus only Upper Paleolithic “modern” hunter-gatherers could have permanent settlements.

The identification of a whole suite of innovations with the onset of the Upper Paleolithic led to the creation of a model that was unquestioned until the late 1980s. This model has been variously labeled;

- the human revolution,

- the creative revolution,

- the dawn of belief, or

- the quantum leap

(Dickson 1990; Mellars 1989; Mellars et al. 2007). For some researchers, the appearance of the Upper Paleolithic in Eurasia at the same time as modern humans was not a coincidence (Mellars 2005). But for others, most of the innovations said to be unique to this period had actually occurred earlier (D’Errico 2003; D’Errico et al. 2003; Nowell 2010). However, as it became clear that there were anatomically modern people in the African Middle Paleolithic as well as at Skhūl and Qafzeh, ideas started to change. While the Upper Paleolithic was still the period associated with modern innovations, it began to be recast as behavioral modernity.

Modern Human Behavior | Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Anthropology

Cultural universals are the key elements shared by all groups of people throughout the history of humanity.

Examples of elements that may be considered cultural universals are:

- language,

- religion,

- art,

- music,

- marriage,

- gender roles,

- the incest taboo,

- myth,

- cooking,

- games, and

- jokes.

While some of these traits distinguish homo sapiens from other species in their degree of articulation in language based culture, they all have analogues in animal ethology. Since cultural universals are found in all cultures including some of the most isolated indigenous groups, scientists believe that these traits must have evolved or have been invented in Africa prior to the exodus.

Classic evidence of behavioral modernity includes:

- finely made stone and bone tools,

- fishing

- evidence of long-distance exchange or barter among groups,

- game playing,

- systematic use of pigment,

- self-ornamentation,

- burial, and

- abstract carvings.

A more terse definition of the evidence is the behavioral B's: blades, beads, burials, bone toolmaking, and beautiful.

The evolution into anatomically modern humans, particularly in brain anatomy, is mostly believed to be a precursor for behavioral modernity and is generally believed to predate it by tens of thousands of years.

It might be thought that BM preceded language but it is evident from the list above that they must have been at least contemporary developments.

Behavioral modernity | Psychology Wiki | Fandom

https://psychology.wikia.org/wiki/Behavioral_modernity

When did something like us first appear on the planet? It turns out there’s remarkably little agreement on this question. Fossils and DNA suggest people looking like us, anatomically modern Homo sapiens, evolved around 300,000 years ago. Surprisingly, archaeology – tools, artefacts, cave art – suggest that complex technology and cultures, “behavioural modernity”, evolved more recently: 50,000-65,000 years ago.

Some scientists interpret this as suggesting the earliest Homo sapiens weren’t entirely modern. Yet the different data tracks different things. Skulls and genes tell us about brains, artefacts about culture. Our brains probably became modern before our cultures.

The “great leap” For 200,000-300,000 years after Homo sapiens first appeared, tools and artefacts remained surprisingly simple, little better than Neanderthal technology, and simpler than those of modern hunter-gatherers such as certain indigenous Americans. Starting about 65,000 to 50,000 years ago, more advanced technology started appearing: complex projectile weapons such as bows and spear-throwers, fishhooks, ceramics, sewing needles.

People made representational art – cave paintings of horses, ivory goddesses, lion-headed idols, showing artistic flair and imagination. A bird-bone flute hints at music. Meanwhile, arrival of humans in Australia 65,000 years ago shows we’d mastered seafaring.

This sudden flourishing of technology is called the “great leap forward”, supposedly reflecting the evolution of a fully modern human brain. But fossils and DNA suggest that human intelligence became modern far earlier.

When did we become fully human? What fossils and DNA tell us about the evolution of modern intelligence

https://theconversation.com/when-did-we-become-fully-human...

First, it is necessary to define terms and establish a few parameters relevant for addressing the origins of cultural modernity. What is cultural modernity? Simply put, this term is used to imply a point in human evolution when people became like us. Implicit in this definition is the view that all living people are cognitively equal regardless of their physical appearance or the kind of technology they use. This Boasian view of the unity of humankind forms the cornerstone of cultural anthropology and the basis of how civilized society deals with cultural diversity

Cultural modernity: Consensus or conundrum? | PNAS

https://www.pnas.org/content/107/17/7621

Homo sapiens emerged once, not as modern-looking people first and as modern-behaving people later.

These people were not “behaviorally modern,” meaning they did not routinely use art, symbols and rituals; they did not systematically collect small animals, fish, shellfish and other difficult-to-procure foods; they did not use complex technologies: Traps, nets, projectile weapons and watercraft were unknown to them.

Premodern humans—often described as “archaic Homo sapiens”—were thought to have lived in small, vulnerable groups of closely related individuals. They were believed to have been equipped only with simple tools and were likely heavily dependent on hunting large game. Individuals in such groups would have been much less insulated from environmental stresses than are modern humans. In Thomas Hobbes’s words, their lives were “solitary, nasty, brutish and short.” If you need a mental image here, close your eyes and conjure a picture of a stereotypical caveman. But archaeological evidence now shows that some of the behaviors associated with modern humans, most importantly our capacity for wide behavioral variability, actually did occur among people who lived very long ago, particularly in Africa. And a conviction is growing among some archaeologists that there was no sweeping transformation to “behavioral modernity” in our species’ recent past.

Refuting a Myth About Human Origins | American Scientist

https://www.americanscientist.org/article/refuting-a-myth-about-human-origins

Our uniquely human ability to learn and use languages (aka language-readiness) has been hypothesized to result from species-specific changes in brain development and wiring that habilitated a new neural workspace supporting cross-modular thinking, among other abilities (Boeckx and Benítez-Burraco, 2014; see Arbib, 2012, 2017 for a similar view).

Strikingly, behavioral modernity did not emerge on a par with cognitive modernity. On the contrary, it is only well after our split from Neanderthals and Denisovans that modern behavior becomes evident around the world (see Mellars et al., 2007; but also Hoffmann et al., 2018; for tentative evidence of behavioral modernity in Neanderthals).

This emergence of modern behavior has been linked to the rise of modern languages, i.e., exhibiting features such as elaborate syntax including extensive use of recursion. The potential of these languages to convey sophisticated meanings and know-how in ways that allows sharing of knowledge with others is assumed to have arisen in a reciprocal relationship with complex cultural practices (Sinha, 2015a,b; Tattersall, 2017). Thus, even if not its main trigger, complex language is at the very least a by-product and facilitator of modern behavior.

Because the human brain and human cognition have remained substantially unmodified since our origins, behavioral modernity and modern languages are assumed to be the product of cultural evolution via niche construction (Sinha, 2009, 2015b; Fogarty and Creanza, 2017). This may include feedback effects of culture on our cognitive architecture in the form of the creation of “cognitive gadgets” (Clarke and Heyes, 2017) through small modifications in learning and data-acquisition mechanisms like attentional focus or memory resources (Lotem et al., 2017), but without involving significant neuro-anatomical changes.

However, this explanation may be insufficient: Recent research suggests that aspects of the human distinctive globular skull and brain might have evolved gradually within our species in response to accompanying genetic changes, reaching present-day human variation between about 100 and 35 thousand years ago (kya), in parallel with the emergence of behavioral modernity (Neubauer et al., 2018). Thus, it may not be entirely appropriate to equate neuro-anatomical modernity with cognitive modernity; instead, the language-ready brain can be conceived of as a brain with the potential for cognitive modernity. Here we argue that these neuro-anatomical and concomitant behavioral changes are largely manifestations of human self-domestication, which constitutes a possible pathway toward cognitive modernity and sophisticated linguistic abilities. We focus specifically on parenting and teaching behaviors as foundations of cultural transmission processes that may have facilitated the exploitation of our cognitive potential and, ultimately, the emergence of modern languages.

The Emergence of Modern Languages: Has Human Self-Domestication Optimized Language Transmission?

https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00551/full

Upper Paleolithic

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Upper_Paleolithic

Origins of society

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Origins_of_society

Early modern human

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Early_modern_human

This paper presents a new line of inquiry into when and how music as a semiotic system was born. Eleven principal expressive aspects of music each contains specific structural patterns whose configuration signifies a certain affective state. This distinguishes the tonal organization of music from the phonetic and prosodic organization of natural languages and animal communication. The question of music’s origin can therefore be answered by establishing the point in human history at which all eleven expressive aspects might have been abstracted from the instinct-driven primate calls and used to express human psycho-emotional states.

The Pastoral Origin of Semiotically Functional Tonal Organization of Music https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7396614/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prehistoric_music

Development of behavioral modernity by hominins around 70,000 years ago was associated with simultaneous acquisition of a novel component of imagination, called prefrontal synthesis, and conversion of a preexisting rich-vocabulary non-recursive communica… | bioRxiv

https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/166520v7

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prehistoric_art

Prehistoric religion

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prehistoric_religion

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Myth_and_ritual

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Religion_and_mythology

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Comparative_mythology

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Religious_behavior_in_animals

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cognitive_science_of_religion

How and why did religion evolve? - BBC Future

https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20190418-how-and-why-did-religion-evolve

Evolutionary origin of religions - Wikipedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Evolutionary_origin_of_religions

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Evolutionary_origin_of_religions

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Evolutionary_psychology_of_religion

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Psychology_of_religion