As a response to the 1920s speculative bubble and Great Crash, the Great Compression and its egalitarian zenith marked the peak of the democratic counterforce.

Family income distribution over the full decade showed much the same: a

shrinking share at the top (and to a lesser extent in the highest

10

percent). The improvement in compensation concentrated in the 50th to 89th

percentiles: the middle class, blue-collar as well as

white-collar.

The Great Compression, so favorable to the middle class and labor

at the

(seeming) expense of the top 1 percent, continued into the 1950s. Politically,

at least, the middle-class ethos ruled. To commentators like Frederick Lewis

Allen, Robert Heilbroner, and David Riesman,

the rich had become “inconspicuous consumers,”

either suffering from a guilt complex

or afraid of giving visible offense.

Their big houses had been sold off to become orphanages or old-age homes, and fewer upper-income families had servants.

In 1953 the new Republican administration of Dwight Eisenhower, far

from imitating the deep tax cuts of Treasury Secretary Andrew

Mellon after the First World War,

decided against seeking a

reduction in the 91 percent top income tax

rate, which

had been kept in effect after World War II...

Wealth & Democracy: Political History of the American Rich –Kevin

Phillips

https://www.amazon.com/Wealth-Democracy-Political-History-American/dp/0767905342

In his book Wealth and Democracy (2002), Kevin Phillips came up with a useful way of thinking about the changing patterns of wealth inequality in the US. He looked at the net wealth of the nation’s median household and compared it with the size of the largest fortune in the US. The ratio of the two figures provided a rough measure of wealth inequality, and that’s what he tracked, touching down every decade or so from the turn of the 19th century all the way to the present. In doing so, he found a striking pattern.

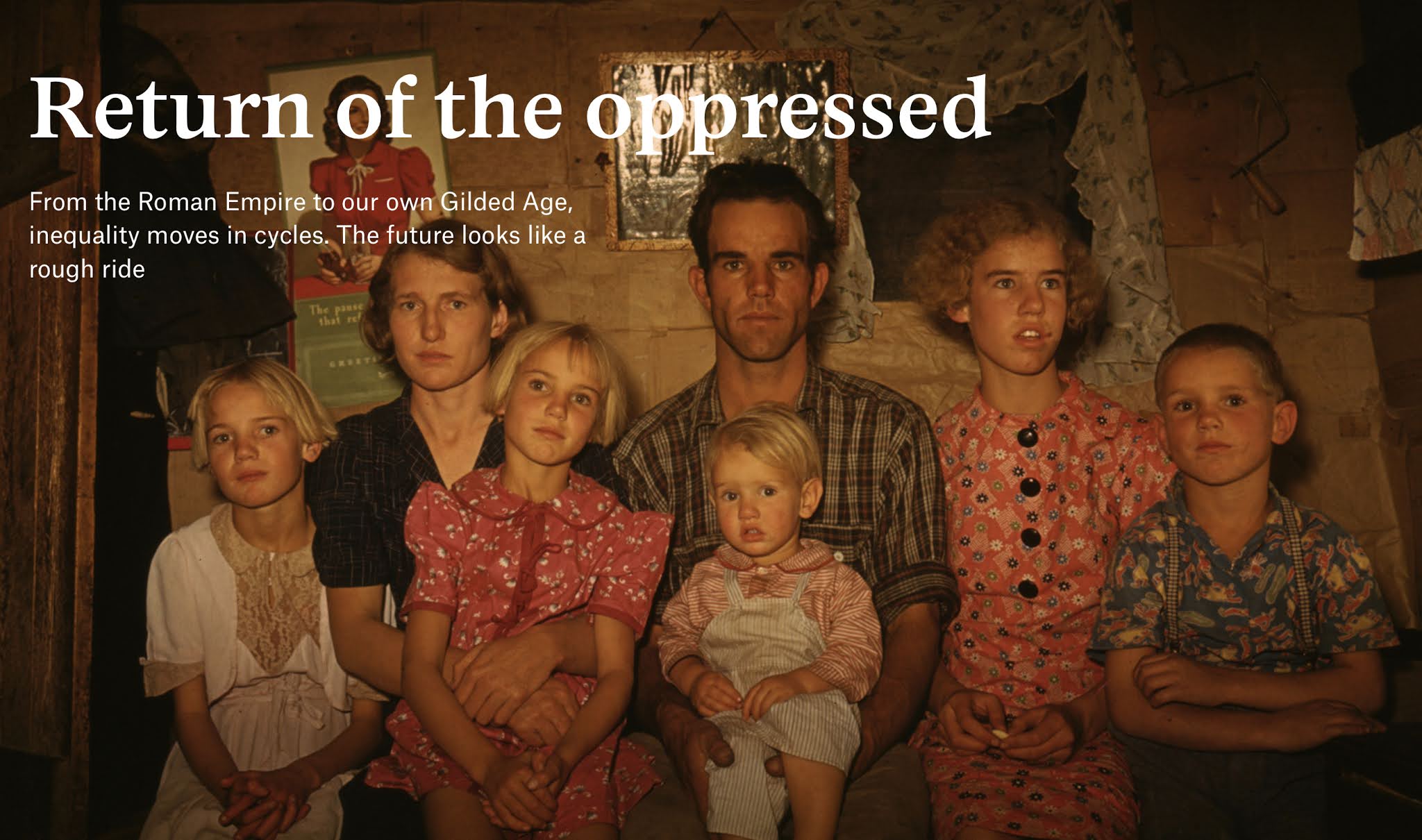

From 1800 to the 1920s, inequalityincreased more than a hundredfold. Then came the reversal: from the 1920s to 1980, it shrank back to levels not seen since the mid-19th century. Over that time, the top fortunes hardly grew (from one to two billion dollars; a decline in real terms). Yet the wealth of a typical family increased by a multiple of 40. From 1980 to the present, the wealth gap has been on another steep, if erratic, rise. Commentators have called the period from 1920s to 1970s the ‘great compression’. The past 30 years are known as the ‘great divergence’. Bring the 19th century into the picture, however, and one sees not isolated movements so much as a rhythm. In other words, when looked at over a long period, the development of wealth inequality in the US appears to be cyclical. And if it’s cyclical, we can predict what happens next.

History tells us where the wealth gap leads

https://aeon.co/essays/history-tells-us-where-the-wealth-gap-leads

From American Exceptionalism to the Great Compression

Jon D. Wisman

The United States was an anomaly, beginning without clear class distinctions and with substantial egalitarian sentiment. Inexpensive land meant workers who were not enslaved were relatively free. However, as the frontier closed and industrialization took off after the Civil War, inequality soared and workers increasingly lost control over their workplaces. Worker agitation led to improved living standards, but gains were limited by the persuasiveness of the elite’s ideology. The hardships of the Great Depression, however, significantly delegitimated the elite’s ideology, resulting in substantially decreased inequality between the 1930s and 1970s. Robust economic growth following World War II and workers’ greater political power permitted unparalleled improvements in working-class living standards. By the 1960s, for the first time in history, a generation came of age without fear of dire material privation, generating among many of the young a dramatic change in values and attitudes, privileging social justice and self-realization over material concerns.

The Origins and Dynamics of Inequality: Sex, Politics, and Ideology

https://oxford.universitypressscholarship.com/view/10.1093/oso/9780197575949.001.0001/oso-9780197575949-chapter-10

The Super-rich: Origin, Reproduction, and Social Acceptance

1 Introduction

The present article and the following Thematic Issue collection deal with a specific and circumscribed topic within the investigations on wealth and on recent trends of social inequalities. Our aim is to dissect the emergence of a reinvigorated group of the super-rich. Although the super-rich constitute a residual class with regard to its number of components, the factors that determine its origin speak to general socio-economic processes; its internal structure reflects the weight of the highest value-added sectors of the economy; and its relevance in terms of power and material resources affects the political spheres, both locally and globally. The super-rich are not a bounded topic. Conversely, they are a relevant and strategic “point of view” for observing socio-economic processes that impact the whole social anatomy (Hedström, 2005).

To take this path, we conceptualize the debate on the super-rich by elaborating three lines of investigation that are relevant to frame the increasing concentration of great wealth.

The first concerns the criteria for identifying the super-rich and the mechanisms through which they have generated and consolidated their wealth over time by means of an exponential growth (Section 2).

The second concerns several aspects related to the lifestyle of the super-rich. To address this issue, we will assume the category of space as a perspective of analysis. Space will be observed with respect to the ability of the super-rich to shape and manipulate places in order to establish their social habitat. Hence, space will also be conceived as social space: the arena of representation and interaction between the super-rich and other social groups (Section 3).

This brings us to the third line of investigation, which concerns the dynamics through which the super-rich obtain legitimacy and social acceptance despite a macroscopic increase in social inequality, both in terms of social polarization — i.e., the growing distances that separate the upper class from the lower one — and growing poverty levels (Section 4).

In the concluding section several regressive outcomes will be presented in economic, social, and political terms related to the concentration of big wealth.

3 The Super-Rich and the Shaping of Social SpacesEven if the super-rich follow part-time or back-and-forth residential patterns, the exclusive urban areas devoted to hosting them must be equipped with “receptive facilities” that the super-rich are likely to use when they are present. As Smeets et al. (2019) have shown, the super-rich more than other people engage in active leisure activities (e.g., socializing, exercising, and heterogeneous hobbies; see Travers, 2019). These activities are carried out in exclusive locations with limited access due to the high prices and for symbolic reasons concerning the status-group membership. These exclusive locations — such as multipurpose sports centres, top-class restaurants, party and cocktail halls, jewellery stores, and high-fashion rooms — are also space-consuming with respect to the urban landscape. Therefore, they fuel phenomena of social segregation and make the super-rich a visible but intangible presence for the social fabric (A.B. Atkinson, 2015).

On closer inspection, several deep aspects of the super-rich lifestyle as a whole seem to combine invisibility and social recognition, thereby nurturing a particular social distinction (Liu & Li, 2019; Cousin, 2017; Savage et al., 2007). Invisibility stems from the spatial separation that affects the super-rich in many urban contexts. Let us remember that the super-rich often pay for receiving absolute luxury services at home such as, for example, exclusive home eating with some of the most famous chefs in the world. Consistently, many super-luxury buildings are places where the super-rich could live without ever heading out3. This is a hyperbolic re-proposition of the gated communities’ model. At the same time, the presence of the super-rich affects the urban landscape with symbols and structures signalling that they are located there. As mentioned, this aspect has culminated in, for instance, the creation in just a few years of an original skyline in several European cities.

This particular combination of invisibility and social recognition also emerges from the opulent consumption patterns of the super-rich, which do not give rise to conspicuous consumption. A hallmark of the exclusivity of consumption by the super-rich is, in fact, removing it from the view of the rest of society. A relevant area of consumption by the super-rich revealing this unique tension between invisibility and social recognition is the art market...

...The second phenomenon is more innovative and concerns experiences of self-segregation of the super-rich in extra-urban areas. In these circumstances, we can identify the formation of new super-rich communities located at the local level, whose origins can be traced back to several social fears that the super-rich face thanks to their privileges...

4 Building Social Acceptance...The study of social acceptance strategies implemented by the super-rich is, in fact, a well-established strand of the literature. The topic has been disentangled with respect to several issues (Sherman, 2019; Serafini & Smith Maguire, 2019).

Some authors, for instance, have investigated how the super-rich use their media representation to gain acceptance and consent. The super-rich are often successful and beloved personalities in the media. In the past, media representations dealt mainly with super-rich family dynasties (e.g., Rothschild, Agnelli) and the big captains of industry (e.g., Ford, Rockefeller). The super-rich family dynasties have lost media appeal, but the media representation of the super-rich as personalities of the star-system — on par with athletes and actors — has grown in recent years. Therefore, the biographies and the undertakings of the super-rich have become a mediatic genre of storytelling. Many super-rich are active participants in the construction of their (auto)biographic representation. Through social media, many of them show glimpses into their everyday life, thereby producing a sort of self-mythization.

The media self-mythization of the super-rich presents several recurring elements (Kets de Vries, 2021). First is the willingness to share private fragilities (i.e., illness or personality disorders), described as an opportunity for redemption. This helps the super-rich demonstrate a gentle form of charisma. Second is the ostentation of having often found themselves, at least once in life, in a position of social marginality. This specific aspect is often represented as the origin of an attitude of breaking established economic routines. Third is, the fact that they like making heretical life choices, similar to retreatism, sensu Merton (1968). Elon Musk, for example, recently sold his properties in San Francisco to move into a modest prefabricated rental house.

Needless to say, these media self-mythizations deliver a sugarcoated version of billionaires’ life-course. This is typical for the media logic, so we should not be surprised. Media must be enjoyed with a degree of “suspension of disbelief”, in the words of Coleridge6. More relevant is to stress that self-mythologizing narratives have helped some super-rich become familiar to a general audience. This has granted social respect towards the super-rich and somewhat weakened the critical orientation for the increasing concentration of wealth. Finally, stories mainly underlying the unique aspects of individual biographies have made great wealth more acceptable (if wealth concentration exclusively depends on individual exceptionalities and not on exogenous benefits, one is inclined to approve it). This has restricted public debate on the role that public resources have played in the success of the super-rich (Mazzucato, 2013).

Another way the super-rich gain social acceptance is through philanthropic activities (McGoey, 2015). It is not of interest here to drill into the individual motivations for private giving. In other words, we will not scrutinize whether the super-rich are driven by altruistic reasons or whether they intentionally use philanthropy as a tool to perpetuate their power (Sklair & Glucksberg, 2021). We will try to pinpoint some consequences of philanthropy occurring regardless the intentionality of the actors.

The new philanthropism is the successful rebranding of an old idea that has “attracted considerable media attention” (McGoey & Thiel, 2018, p. 115) in recent years...

...Other aspects are even more relevant for our analytical purposes. Beyond the dark sides of philanthropy as such, it is interesting to recall here the main mechanism through which philanthropy has become a factor sustaining the social acceptance of the super-rich (Sklair & Glucksberg, 2021; McGoey, 2012). In this respect, this mechanism relates to the idea that enlightened self-interest produces positive externalities for the public good (McGoey & Thiel, 2018, p. 116). As a result, it is taken for granted that the huge concentration of private wealth has positive effects for society as whole. In fact, it is assumed that big wealth provides the resources to address enormously costly issues that politics cannot handle because it is short of resources. We must only hope that the super-rich keep reproducing themselves over time, and have them follow the model of Frederick II of Swabia, thus becoming patrons of science, arts, and social welfare. This reasoning has some weaknesses, however. Are we actually dealing with independent variables? Big and concentrated private wealth in the face of few public resources is not a separate phenomenon...