Stealth Authoritarianism

https://immortalista.blogspot.com/2022/08/stealth-authoritarianism.html

Defending Our Constitution Requires More Than Outrage

Newspapers still publish but are bought off or bullied into self-censorship. Citizens continue to criticize the government but often find themselves facing tax or other legal troubles. This sows public confusion.

Many continue to believe they are living under a democracy.

Because there is no single moment – no coup, declaration of martial law, or suspension of the constitution – in which the regime obviously “crosses the line” into dictatorship,

{ nothing may set off society’s alarm bells }

https://immortalista.blogspot.com/2022/08/how-democracies-die.html

As we mark the 56th anniversary of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, @StaceyAbrams and I are calling on you to reach out to your members of Congress and ask them to pass the For the People Act and John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act. Join us: https://t.co/sF2aVjWPah pic.twitter.com/SontjePnLt

— Michelle Obama (@MichelleObama) August 5, 2021

The Evolution of the Strongman

Even as news programs sound alarms about democracy in crisis, the truth is that authoritarian regimes govern a smaller percentage of the world’s countries today than at any time in the post-World War II era. The percentage of authoritarian regimes in power peaked in the late 1970s at the height of the Cold War, reaching about 75 percent. By 2000, just under 50 percent of countries were governed by authoritarian regimes. As of 2017, a scant 38 percent were.

So why all of the doomsday talk about rising authoritarianism? Well, although it has become somewhat rare for democracies to fully collapse into autocracy—indeed only two arguably did so in 2016 (Turkey and Nicaragua) and none in 2017—many democracies today are moving in the authoritarian direction. This is troubling because, historically speaking, when democracies deteriorate they usually don’t bounce back quickly.

Even more worrying, many of the countries suffering democratic breakdown today are not the ones we’d expect.

A wide body of political science research has shown that the richer the democracy, the more resilient it is supposed to be. Yet, recent data indicate that the democracies falling apart today are quite a bit richer than those in earlier decades.

In the 1990s, the per capita wealth of the typical democracy that collapsed was about $1,700. This figure, adjusted for inflation, grew to about $2,300 in the 2000s and to about $3,300 in the 2010s. The trend runs counter to some long-held beliefs about the dynamics of political change. It suggests that

greater wealth may no longer protect democracies as well as it did in the past, which is perhaps why developments in Hungary, Poland, and elsewhere have generated such surprise and concern.

Turkey offers an unsettling example of what may lie ahead. Recep Tayyip Erdogan came to power in 2003, via parliamentary elections that by all accounts were democratic. Turkey had experienced interludes of military rule in the past, but few would have put it on the list of contenders for autocratic breakdown at the time of Erdogan’s assumption of control. Not only was it comparatively wealthy, but it also featured a rising middle class and bustling civil society.

Yet, over the course of his time in power, Erdogan has initiated a series of actions that have chipped away at Turkish democracy, including cracking down on intellectuals critical of the government and engaging in efforts to muzzle the media and otherwise sideline opponents. In 2016, the situation escalated. Erdogan supporters took control of several media outlets, branded academics opposing him as “treasonous” (leading to job losses for many), and initiated changes to the constitution that gave him extensive new powers. The failed coup that year was the tipping point, paving the way for a three-month state of emergency, which led to a widespread purge of government opponents. The overall process was slow and incremental—typical of most democratic breakdowns today—but the deterioration of democracy, according to rankings by the Economist, was nearly complete by the end of that year.

IRONICALLY, IF DEMOCRACIES THAT once seemed safe have slipped, { today’s authoritarian regimes have grown more liberal } at least in terms of their facades.

Since the end of the Cold War, the majority of the world’s authoritarian regimes have featured legislatures, multiple political parties, and somewhat competitive elections that are held on a regular basis. The evidence indicates that they are wise to do so: Authoritarian regimes with pseudo-democratic institutions last quite a bit longer in power than those without them. Astute autocrats have learned that a semblance of political pluralism offers many advantages and fewer risks than traditional tactics of control such as brute repression.

{ Today’s authoritarian regimes have grown “smarter” } in other domains as well, beyond political institutions. Their goal is to mimic the virtues of democracy, such as accountability, contestation, and representation, using methods that are superficial and fall short of real reform. Examples are wide-ranging, including legalizing nongovernmental organizations—but only those that secretly promote the government agenda—and using election monitors—but only those that validate the government’s intended result. Many of today’s authoritarian regimes even pay for public relations firms to sell a positive image of their government domestically and overseas. All of these moves enable authoritarian governments to pretend to be democratic while making it more difficult to charge that they are not.

Singapore may be the best exemplar of the model. The People’s Action Party regime has governed since 1965. It regularly holds elections and even allows members of the opposition to win seats in the legislature. Although its elections seem competitive, the regime reportedly engages in subtle strategies to ensure that it maintains control. For example, it has used defamation lawsuits allegedly as a way to stifle its opponents. When opponents lose the lawsuits, they are forced to pay sizable financial damages, which eventually leads them to bankruptcy. Likewise, the Singaporean regime has created such programs as Reaching Everyone for Active Citizenry @ Home, which is part of its Ministry of Communications and Information and gathers citizen feedback on major issues. These programs provide the regime access to citizen preferences and beliefs, and they may ultimately serve as a tool for critical intelligence-gathering. The Singaporean regime’s skillful adoption of the trappings of democracy perhaps accounts for its longevity: It has been in power more than 50 years.

Indeed, the movement toward greater false liberalism among contemporary authoritarian regimes seems to have proved effective across the board. Although there are fewer authoritarian regimes governing than in decades past, those that remain are remarkably durable.

- During the Cold War, the typical authoritarian regime governed for about 12 years.

- This number increased to 19 years in the 1990s and 22 years in the 2000s;

- It has now climbed to 27 years in the 2010s.

Gone are the days of the military junta that takes power only to be forced to leave it a few years later. { Today’s authoritarian regimes have learned that feigning democratic rule has survival benefits }

The takeaway point from these trends is that our understanding of what is “normal” in the political landscape may need updating.

- Although it is true that more of the world is democratic than ever before, there are signs that progress may soon come to a halt.

- Democracies are gravitating toward authoritarianism in a number of surprising places, such as Hungary, Poland, and even the United States.

At this point, we can only speculate as to why this is happening now. Likely causes include citizen disillusionment on the heels of the migration crisis, rising inequality, and stagnating standards of living.

Regardless, although we have traditionally viewed the developed world as immune to this sort of thing—especially democratic backsliding evolving into full democratic breakdown—we no longer can.

Meanwhile, today’s authoritarian regimes are making it more difficult to brand them as such. They are increasingly mimicking the traits of democracy, in ways that seem liberal but actually work to extend the authoritarian lifespan.

However, the message is not all gloom and doom. Although authoritarian regimes with pseudo-democratic institutions are longer-lasting, when they do collapse, they are more likely to transition to democracy than to another dictatorship.

The experience of Malaysia gives particular cause for optimism. The dominant-party regime had been in power since 1957. It evolved its tactics in all the ways outlined here—and by all accounts was a very clever government. Few experts anticipated that the regime would lose (and respect the outcome of) the 2018 elections. Yet it did, and now Malaysia is democratic for the first time in its history. Even savvy authoritarian regimes sometimes miscalculate. If future democratizations are similar to Malaysia’s—occurring at the ballot box rather than through disruptive protests or force—this would be one trend that bodes well for global peace and stability.

The Evolution of the Strongman

https://foreignpolicy.com/2019/03/11/the-evolution-of-the-strongman/

Why the World Should be Worried about the Rise of Strongman Politics

Spread of Authoritarianism …The politics of fear and resentment … is now on the move. It’s on the move at a pace that would have seemed unimaginable just a few years ago. I am not being alarmist, I’m simply stating the facts. Look around – strongman politics are on the ascendant.

Trump, therefore, is not an aberration. He is { part of a strengthening authoritarian trend more or less across the globe }

In the Middle East, the Arab Spring has given way to the entrenchment of dictatorships in places like Syria, where Bashar al-Assad has reasserted his grip on power with Russian and Iranian help, and in Egypt, where strongman Abdel Fattah al-Sisi continues to curtail press freedom and incarcerate political rivals.

In Europe, the rise of an authoritarian right in places like Hungary, Austria and now Italy are part of this trend. In Italy, the bombastic Silvio Berlusconi proved to be a forerunner of what is happening now.

In China, Xi Jinping’s “new era” is another example of a strongman overriding democratic constraints, with term limits on his leadership having recently been removed.

In the Philippines, Rodrigo Duterte is using his war on drugs for broader authoritarian purposes in the manner of a mob boss.

In Thailand, the army shows little inclination to yield power it seized in a military coup in 2014, even if there was public clamour for a return to civilian rule (which there is not).

In Turkey, Recep Tayyip Erdogan is continuing to strengthen his hold on the country, expanding the powers of the presidency and locking up political rivals and journalistic critics. As a result, Turkey’s secular and political foundations are being undermined.

In Brazil, 40% of those polled by Vanderbilt University a few years back said they would support a military coup to bring order to their country, riven by crime and corruption.

And in Saudi Arabia, a young crown prince, Mohammed bin Salman, has detained the country’s leading businessmen and extorted billions from them in return for their freedom. This took place without censure from the West.

The Death of Truth

{ Genuine liberal democrats are in retreat as a populist tide laps at their doors }

In Britain, Theresa May is hanging on to power by a thread against a revanchist threat from the right.

In France, Emmanuel Macron is battling to transform his welfare-burdened country against fierce resistance from left and right.

In Germany, Angela Merkel, the most admirable of Western liberal democratic leaders, is just holding on against anti-immigration forces on the right.

In Australia, Malcolm Turnbull and Bill Shorten, the leaders of the established centre-right and centre-left parties, are similarly under pressure from nativist forces on the far right.

WHAT AUSTRALIA AND THESE OTHER countries lack is a Trump, but anything is possible in an emerging strongman era, including the improbable – such as the emergence of a reality TV star as leader of the free world.

In a recent Lowy Institute opinion survey only 52% of younger Australians aged 18-29 years believed that democracy was preferable to other alternative forms of government.

In all of this,

truth in particular is among the casualties. All politicians bend the truth to a certain extent, but there is no recent example in a Western democracy of a political leader who lies as persistently as Trump.

Like the character Willy Loman in Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman, Trump lives in his own

- make-believe reality TV world where facts, it seems, are immaterial.

- Inconvenient information can be dismissed as “fake news”.

- Those who persist in reporting such inconvenient truths are portrayed as “enemies of the people”.

This is the sort of rhetoric that resides in totalitarian states, where

the media are expected to function as an arm of a dictatorship or, failing that, journalists are simply disappeared. In Putin’s Russia, journalist critics of the regime do so at their peril.

In his lecture in South Africa, Obama dwelled at length on the corruption of political discourse in the modern era, including a basic disrespect for the facts.

People just make stuff up. They just make stuff up.

- We see it in the growth of state-sponsored propaganda.

- We see it in internet fabrications.

- We see it in the blurring of lines between news and entertainment.

- We see the utter loss of shame among political leaders where they’re caught in a lie and they just double down and they lie some more.

It used to be that if you caught them lying they’d be like, ‘Oh man.’ Now they just keep on lying.

In the digital era, it had been assumed technology would make it easier to hold political leaders to account. But, in some respects, the reverse is proving to be the case, as Ian Bremmer, author of Us vs. Them: The Failure of Globalism, wrote in a recent contribution to Time.

A decade ago, it appeared that a revolution in information and communications technologies would empower the individual at the expense of the state. Western leaders believed social networks would create ‘people power’, enabling political upheavals like the Arab Spring. But the world’s autocrats drew a different lesson. They saw an opportunity for government to try to become the dominant player in how information is shared and how the state can use data to tighten political control.

In his conclusion, Bremmer has this sobering observation:

Perhaps the most worrying element of the strongman’s rise is the message it sends. The systems that powered the Cold War’s winners now look much less appealing than they did a generation ago. Why emulate the US or European political systems, with all the checks and balances that prevent even the most determined leaders from taking on chronic problems, when one determined leader can offer a credible shortcut to greater security and national pride? As long as that rings true, the greatest threat may be the strongmen yet to come.

Why the world should be worried about the rise of strongman politics

Why Strongmen Win in Weak States

After five years of populist breakthroughs across Europe, the United States, Latin America, and South and Southeast Asia, scholars are far from discovering any “universal theory” that can explain why illiberal politicians appeal to voters in every time and place. Yet in the context of Western societies, at least, recent theories examining the respective roles of “economic grievance” and “cultural backlash” have helped to shed some light on the issue. On the one hand, scholars such as Barry Eichengreen, Dani Rodrik, and Hanspeter Kriesi have examined how

the economic disruptions caused by globalization, including rising income inequality, have led voters in the West’s “left-behind” industrial and rural regions to support extremist parties such as the French National Rally or Greece’s Golden Dawn.

On the other side of this debate, scholars such as Ronald Inglehart and Pippa Norris have shown how

the political divide between prosperous metropolitan areas and conservative hinterlands in Europe and the United States is rooted not only in socioeconomic disparities, but also in diverging values and beliefs, as formerly dominant groups react against socially progressive policies.

Democratization and State-Building

To understand the rise of authoritarian strongmen in developing democracies, then, it is important to recognize the divergence of state-building trajectories and democratization trajectories over recent decades. In the early twenty-first century, democratic reform and building state capacity were generally seen as complementary processes, with international policy makers advocating competitive multiparty elections as a solution for countries facing problems ranging from endemic corruption to state fragility to gaps in infrastructure or welfare provision. Yet the reality is that elections by themselves cannot guarantee progress on the road to building an effective bureaucracy, clamping down on organized crime, or ensuring the efficient and equitable provision of schools, roads, and hospitals. Across the world there is wide variation in the degree to which new democracies have succeeded in building effective institutions and strengthening public accountability (Figure 1), and this divergence may help to explain when and where authoritarian challengers emerge triumphant.

Since the “third wave” of democratization that occurred across the world from the 1970s to the late 1990s, there have undoubtedly been success stories, in which democratic transition has brought newfound scrutiny of senior politicians by journalists and activists. In South Korea, for example, the 2016–17 “candlelight revolution”—which brought improved executive oversight after years of presidential scandals—provides a demonstration of the robust democratic culture that has taken shape since the country’s 1987 transition. In Taiwan, a “bureaucratic authoritarian” state has been steadily transformed into a democracy with robust civic engagement, most recently notable for its role in combatting the novel coronavirus pandemic. In postcommunist Europe, the three Baltic states have shown how in the span of one generation, cohesive national elites can steer a country through a transition from authoritarian central planning to a regulated market economy under democratic rule. And in one of the world’s largest new democracies, Indonesia, a combination of radical decentralization and top-down enforcement from Jakarta are starting to check the distributed system of clientelism that replaced the centralized kleptocracy of the Suharto years. For scholars of democracy, these “success stories” highlight an important point: Simultaneous democratic transition and state-building are possible, and can be achieved across diverse regions and stages of economic development.

Skeptics of democratic state-building, however, have no shortage of counterexamples to draw upon. Across Latin America, Africa, and both Southern and Eastern Europe, newly elected governments have struggled to overcome endemic problems of corruption, criminality, and state fragility. These difficulties are reflected across a wide range of indicators, ranging from homicide rates to assessments of the ease of doing business to ratings of bureaucratic quality. But if we restrict ourselves to a fairly conventional measure for some of the world’s largest new democracies—Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index—we can see that in the last decade alone Brazil has fallen from 75th to 105th place, Mexico from 89th to 138th, and South Africa from 55th to 73rd position.

So why have public accountability and transparency eroded in so many young or reemerging democracies? There is not a single explanation that fits all cases. In countries where political parties swept to power with ambitious social-reform agendas, clientelism has grown as direct party-to-voter channels have been used to distribute public goods and benefits, leading to resentment over unequal access to resources. In South Africa, for example, the state apparatus developed since 1994 under the aegis of the dominant African National Congress has largely relied on patronage networks extending from that party, leading to a situation where patronage networks work “in parallel with, and sometimes in opposition to, the impersonal political institutions of the state.” Similarly in postauthoritarian Greece, the distribution of public jobs and contracts to party supporters began under Andreas Papandreou in the 1980s, while in Brazil and the Philippines political parties have long existed primarily as vehicles for channeling resources to political clans.

Even in countries where voters are not offered privileged access to benefits in exchange for political support, political parties may seek to undermine the bureaucracy’s independence in order to gain a strategic advantage over their rivals. This can be seen in postauthoritarian polities that engage in selective policies of lustration—that is, the removal of civil servants who ostensibly have ties to the former regime, but in practice are not members of the governing party. In Ukraine, for example, a 2014 lustration policy purged seven-hundred officials who had served in the administration of ousted president Viktor Yanukovych, while in Hungary Viktor Orbán has justified his attacks on the independence of the courts and the civil service with claims that these institutions represent the forces of communism.

Finally, a very different problem faced by many new democracies is the persistence and growth of organized crime and criminal violence. Urban security has deteriorated across much of Latin America, sub-Saharan Africa, and Eastern Europe in the decades following democratic transition. In particular, this problem has been exacerbated in countries where the security services were tarnished by their association with a former dictatorship, and have faced chronic underfunding since its fall. In Brazil, for example, the murder rate during the final years of military rule was similar to the 10 per 100,000 rate found in the United States at that time, but five years after democratization had already doubled to 20 deaths per 100,000. It reached a record high of slightly above 30 per 100,000 in the year before the 2018 election of Bolsonaro, whose presidential campaign had promised to liberalize gun laws (enabling Brazilians to “defend themselves”) and give security forces the right to “shoot and kill” armed criminals. In Russia, the murder rate also soared to more than 30 per 100,000 during the first decade after the Soviet collapse. Finally, in the decade leading up to Duterte’s 2016 election as president of the Philippines, the country’s murder rate climbed from about 7 to 11 per 100,000, creating popular support for calls for harsh measures to restore urban security. In much of Eastern Europe and Latin America, not only criminal violence but also the growth of organized criminal networks threatens perceptions of democratic state efficacy. These groupings now form a shadow export sector, based upon the trafficking of narcotics, arms, sex workers, and undocumented migrants to major cities in Western Europe or North America, that runs in parallel to the official supply chains of the global economy.

Regardless of their exact nature, shortcomings in state capacity and the rule of law pose a serious challenge to the legitimacy of new democracies. Although political science teaches scholars to distinguish between “state legitimacy,” “regime legitimacy,” and “government legitimacy,” these three concepts are rarely so discrete in the minds of citizens. A newborn democracy in a state that is failing to contain corruption, conflict, or criminality will take on these attributes as its own in the public mind. Meanwhile, a succession of elected governments that become mired in scandal and policy paralysis will undermine civic evaluations of the democratic system as a whole, and not simply evaluations of individual administrations.

This can be seen from Figure 2, which shows the relationship between changes in citizen evaluations of democracy—the average response when publics are asked if they are “satisfied” with the functioning of their democratic system—and changes in levels of corruption, as measured by the Worldwide Governance Indicators. The trend is clear: In those new democracies that have seen the greatest improvements in transparency and accountability in public life, satisfaction with the political system has risen. That is the case for the Baltic states, Taiwan, and South Korea. Yet in democracies where accountability has deteriorated most sharply, it is evident that public satisfaction has collapsed. This pattern can be observed in countries such as Greece, Brazil, and South Africa.

The Rise of Authoritarian Populism

Once we consider the effects of inadequate state capacity, the rise of “strongman” leaders across emerging democracies becomes a great deal less puzzling. Figures such as Putin in Russia, Modi in India, or Turkey’s Recep Tayyip Erdoğan win support by pledging to bring back public order, state authority, and national pride, in the context of political systems exhibiting various pathologies of state failure. In early twenty-first century Russia, for example, Putin’s promise to “restore the power vertical” and end a decade of delayed salary payments, urban violence, and petty corruption proved critical to winning the support of the country’s fragile middle class, and this promise remains key to the loyalty of his dwindling support base today. In the Philippines, a sense of physical insecurity among the country’s swelling urban population, shaken by a homicide rate that has soared in the last decade, helps to explain why between seven and eight out of ten Filipinos continue to support Duterte’s brutal “war on drugs” despite its heavy toll in lives lost and rights violated. And in Brazil, almost 70 percent of voters in São Paulo state voted for Bolsonaro in the 2018 presidential runoff not because of any newfound distaste for homosexuality—after all, the state’s capital has hosted the world’s largest gay-pride parade annually for almost two decades—but due more to widespread disgust with political corruption, despair at the persistence of urban crime, and sympathy with calls for harsh measures to restore “order and progress.”

A similar misunderstanding is common in analysis on other emerging democracies, where the opposition of “cosmopolitan liberalism” to “social conservatism” does a poor job of explaining the salient social cleavages and dividing lines between political parties. In Poland, for example, both the populist Law and Justice party (PiS) and the more moderate Civic Platform opposition rose to prominence in the early 2000s on socially conservative platforms, advocating stances against abortion, gay marriage, and secular schooling that were broadly in line with majority public opinion. The real difference between the parties was the prominence given by PiS to issues of anticorruption and social justice, in the wake of bribery scandals that had brought down the rival Democratic Left Alliance.

In particular, the party chose to decry what it termed “Latinization”: the nexus of economic privilege, political connections, and unequal access to justice depicted as characteristic of Latin American societies and, to a lesser extent, the countries of Southern Europe. One prong of PiS’s approach was to promote welfare programs for those in “left-behind” regions of the country, while the second was a “law and order” campaign that became increasingly populist in both style and implementation. Ministers during the party’s first stint in government, from 2005 to 2007, went so far as to arrange televised arrests of alleged offenders, which proved widely popular despite their reliance upon weak or circumstantial evidence.

This intersection of the populist style with preexisting social and institutional grievances is critical to understanding populist breakthroughs across developing democracies. It is true that populist politicians are often distinguished by a rhetorical approach that, as Cas Mudde’s classic definition puts it, contrasts the “pure people” with a “corrupt elite.” Yet to cast populism simply as a rhetorical device risks ignoring its contextual significance in developing democracies where malfeasance in office is in fact relatively widespread, and deep inequalities do in fact separate political elites from the rest of society. This can also help to explain why conspiracy theories, which play a central role in populist discourse, have greater resonance in countries with dense elite networks facing only fragmentary exposure to the public eye.

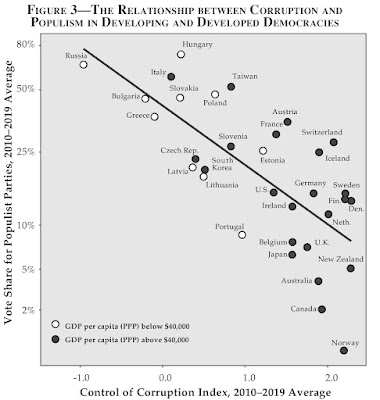

In a democracy where investigative reporting does at regular intervals expose conspiracies and malfeasance among key political, economic, and bureaucratic actors, it is difficult to dismiss such theories out of hand, and any such accusation begins from a baseline level of “truthiness.” For concerned citizens, the line between “pragmatic skepticism” and simple naïveté is blurred; there emerges a form of “post-truth politics” in which any number of plausible yet unverified claims can be circulated about one’s political opponents, leaving the average voter adrift on a sea of half-facts and falsehoods. It is therefore unsurprising that among both developed and developing democracies the relationship between support for populist politicians, who habitually lambaste corruption among elites, and the objectively assessed level of corruption is fairly strong (Figure 3). This suggests that the appeal of such anti-elite messaging is due at least in part to the behavior of elites themselves and the plausibility of conspiracy accusations, regardless of whether they turn out to be real or fictitious.

The rise of “authoritarian populism” in developing democracies, in short, may require an explanation that is quite different from the theories about cultural backlash or the economically “left-behind” that are commonly applied to mature democracies. In polities where elites are distrusted, parties are weak, and welfare systems are clientelistic, antisystem movements that promise to overhaul the status quo may make broad inroads among middle-class voters, as well as among poorer voters tired of endemic corruption and urban insecurity. Meanwhile, in democracies where elite networks conceal genuine malfeasance among politicians, businessmen, and career bureaucrats, the conspiracy accusations promulgated by populist demagogues find broad resonance in society—and not simply among those who are less educated or especially credulous.

This relationship has a number of implications, most importantly for democratic stability. In mature democracies such as the Netherlands or Denmark, populists are first and foremost identitarians campaigning on a platform of grievance, and this curtails their electoral appeal to at most a third of the vote. They must compete with an established moderate center-right that remains appealing to the median middle-class voter, and in this context they frequently struggle to make inroads among citizens who value traditional conservative goals such as stability, accountable governance, or “law and order.”

Where populist parties are able to enter government, as they have in Austria and Denmark, it is only by forming coalitions with establishment conservatives, who limit their partners’ capacities to damage liberal and democratic institutions. In this way, as Daniel Ziblatt has argued, conservative parties may play an essential role in preserving democratic stability today, as they have done in Europe historically. And as James Loxton contends, the same may be true in postauthoritarian regimes where former elites form “successor parties” bound to the democratic rules of the game.

In fragile democracies, by contrast, authoritarian populists are able to sweep to power by combining a narrow identitarian support base with a much broader coalition of supporters among the urban middle class, who are motivated by the desire for public order, accountability, and an end to clientelism and graft. This is clear within movements such as Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) in India, which must balance its religious-nationalist “Hindutva” wing against reformist supporters in the urban middle classes, but is also evident elsewhere. Putin’s early administrations, for example, included relatively liberal and Westernizing reformers such as Andrei Illarionov, Alexei Kudrin, and Hermann Gräf alongside the “siloviki” network brought in from the security services. In Brazil, Bolsonaro’s government initially included reformist technocrats such as economist Paulo Guedes or the (now departed) judge Sérgio Moro alongside ideologues such as Foreign Minister Ernesto Araújo. These choices satisfied the swing voters who, tempted by promises of order and reform following the mammoth Lava Jato corruption scandal, opted for Bolsonaro in the second round of the 2018 election. Finally, Erdoğan’s governments in Turkey have included technocratic reformers such as Ali Babacan, the deputy prime minister who was previously responsible for IMF-negotiated reforms and EU accession talks, and Ahmet Davutoğlu, who before serving as prime minister (2014–16) inspired the government’s “dual-track” foreign policy of seeking both “neo-Ottoman” influence in the Middle East and eventual EU membership.

Coalitions of this kind are a response to real societal problems, but it is precisely the convergence of interests between populist currents and pragmatic reformers that imperils democratic survival. It is far easier for authoritarian populist leaders to enter office where public institutions and norms of accountability have decayed, because this allows such leaders to reach out beyond their ideological base and tap into a broader upswell of antiestablishment feeling—both among voters and among figures within the technocratic elite itself, with the latter’s participation adding legitimacy to the populist cause. Then once such temporary alliances have smoothed a populist’s path to power, they may give way to a more complete consolidation of personalist rule after liberal reformists are marginalized.

We have seen this pattern in Russia since Putin’s return to the presidency in 2012, in 1990s Peru following Alberto Fujumori’s “self-coup,” and in Turkey following Erdoğan’s 2017 constitutional reforms. In the latter case, Erdoğan’s own premier and vice-premier, Davutoğlu and Babacan, went from leading the government to founding opposition parties committed to restoring parliamentary democracy and reversing the authoritarian drift that had occurred on their watch. In this way, technocratic and liberal reformists can end up facilitating an authoritarian turn, much as they may attempt to resist this tendency from the inside—and even if they eventually join forces with their onetime civic opponents on the streets.

Democracy’s Prospects

A generation has passed since the onset of the third wave of democratization, while we are more than a decade into a phase of populist mobilization sweeping both developing and developed democracies. It is therefore possible to begin drawing some general conclusions regarding the subsequent trends in democratic performance, their implications for the health of democratic institutions, and prospects for the future.

While there are individual cases of countries that have managed to achieve state strengthening and political liberalization simultaneously, the general record among new democracies has been disappointing. In many countries, bureaucratic structures inherited from authoritarian regimes have been subject to attrition and clientelism. Elected politicians have used public-sector jobs as a form of patronage, engaged in partisan vetting and lustration of civil servants, tolerated corruption among party allies, and politicized formerly autonomous government agencies. Meanwhile, persistent challenges of organized criminality and violence have beset new democracies in Latin America, Eastern Europe, sub-Saharan Africa, and Southeast Asia. These shortcomings have not only eroded support for the first generation of posttransition political elites, but also led to fraying confidence in liberal democracy among the growing urban middle class. For this reason, authoritarian politicians promising to cut through the gridlock and “make tough decisions” have acquired a mass base of political support. In many cases, they have managed to gain elected office, and from that position have begun eroding democratic rights and freedoms—by pursuing authoritarian approaches to law and justice or to fighting ethnic insurgency, and by removing legislative checks and balances while consolidating their own power.

Yet there are still reasons for optimism when it comes to the challenge of authoritarian populism in fragile democracies. First, in democracies suffering from persistent graft, scandal, and maladministration, populist movements—whether authoritarian or not—frequently serve as magnets for individuals attracted by the goal of political reform, and are sometimes capable of delivering positive measures when in office. As in the classic visual illusion, such parties may appear alternately as both the “duck” of populism and the “rabbit” of democratic refoundation, with no clear indication as to which form they will finally take. In Ukraine, for example, Volodymyr Zelensky’s 2019 candidacy had all the hallmarks of a populist campaign: Zelensky was a celebrity outsider lacking a political party, a policy platform (beyond overturning the political duopoly of then-president Petro Poroshenko and former prime minister Yulia Tymoshenko), or political experience (beyond performing as a Ukrainian president in a comic television series). Yet Zelensky’s campaign attracted veterans of the 2013–14 EuroMaidan protest movement, and his administration implemented serious governance reforms during its first year in office, even if this momentum has since faded.

Similarly, Italy’s Five Star Movement includes under its broad tent a panoply of conspiracy theorists, postcommunist radicals, and graduates of the country’s many anticorruption campaigns, and it has now swung its support behind a technocratic administration led by former law professor Giuseppe Conte. The confusing reality of course is that such parties are both “duck” and “rabbit” simultaneously—they genuinely do include both populist extremists and idealistic reformists, and for a long period may oscillate between these tendencies. And this same contradiction lies at the heart of more authoritarian forms of populism, such as that of India’s BJP or Bolsonaro’s founding cabinet of ideologues and technocrats. The “Janus-like” fusion of populist authoritarians and reformist technocrats does for a time yield genuine opportunities for governance reform, with no clear indication as to which faction will ultimately predominate.

Second, right-wing populist administrations may eventually moderate to form establishment conservative parties within stable multiparty systems. Models for such a trajectory can be found in the political histories of established democracies—the 1958 refounding of the French Republic under General Charles de Gaulle, for example, or the evolution of authoritarian “successor parties” into moderate conservative parties in many new democracies, as illustrated for instance by the Alianza Popular in post-Franco Spain. The tension within “law and order” populist movements between their more liberal, technocratic wing and their illiberal, identitarian, and authoritarian leadership is a genuine political contest—and one in which moderates do sometimes prevail, not least when the founding autocrat passes from the scene. And even when populist leaders manage to concentrate power in their individual office rather than in the ruling party—as Putin has done in Russia and Erdoğan has done in Turkey following the 2017 constitutional referendum—this frequently alienates moderate insiders, who then become a source of credible and experienced opposition. In addition to the abovementioned defection of Erdoğan’s top officials, examples include an oppositional turn by Fujumori’s 1990 presidential running mate following the 1992 Peruvian autogolpe, or former prime minister Mahathir Mohamad’s spectacular unseating of his own chosen successor in alliance with a jailed opposition leader during Malaysia’s 2018 election.

These observations give cause for hope regarding the future of back-sliding democracies. It is by no means inevitable that, once started down the road of democratic decay, a country will continue until it reaches consolidated authoritarianism. Democratic consolidation may be hard, but authoritarian consolidation is a great deal harder. Not only does the personalistic nature of populist movements make them vulnerable to changes of leadership, but factions within them may be far more amenable to political liberalization than is commonly appreciated, as the past decade’s steady defection of liberal reformists from the Putin and Erdoğan administrations illustrates. In this respect it is also important to learn from the experience of third-wave democratizations, in which internal reformists such as Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev or Taiwan’s Lee Teng-hui often played pivotal roles in paving the road to political liberalization. Working with such actors may be distasteful to many Western NGOs and activists. But if or when there is a fourth wave of democratization, its prospects for success may depend as much on reformist successors located within today’s populist movements as on liberal dissidents without.

Why Strongmen Win in Weak States | Journal of Democracy

https://www.journalofdemocracy.org/articles/why-strongmen-win-in-weak-states/

More on Authoritaianism here;

https://www.journalofdemocracy.org/

by Arch Puddington

Key Findings

- Modern authoritarianism has succeeded, where previous totalitarian systems failed, due to new strategies of repression, the exploitation of open societies, and the spread of illiberal policies in democratic countries themselves.

- Russia, under President Putin, has played an outsized role in the development of modern authoritarian systems, especially in media control, propaganda, the smothering of civil society, and the weakening of political pluralism.

- The toxic combination of unfair elections and “majoritarianism” is spreading to illiberal leaders in what are still partly democratic countries. Increasingly, populist politicians—once in office—claim the right to suppress the media, civil society, and other democratic institutions by citing support from a majority of voters.

- The hiring of political consultants and lobbyists from democratic countries to represent the interests of autocracies is a growing phenomenon. China is in the vanguard, but there are also K Street representatives for Russia, Kazakhstan, Azerbaijan, Turkey, Ethiopia, and practically all of the authoritarian states in the Middle East.

Executive Summary

The 21st century has been marked by a resurgence of authoritarian rule that has proved resilient despite economic fragility and occasional popular resistance. Modern authoritarianism has succeeded, where previous totalitarian systems failed, due to refined and nuanced strategies of repression, the exploitation of open societies, and the spread of illiberal policies in democratic countries themselves. The leaders of today’s authoritarian systems devote full-time attention to the challenge of crippling the opposition without annihilating it, and flouting the rule of law while maintaining a plausible veneer of order, legitimacy, and prosperity.

Central to the modern authoritarian strategy is the capture of institutions that undergird political pluralism. The goal is to dominate not only the executive and legislative branches, but also the media, the judiciary, civil society, the commanding heights of the economy, and the security forces. With these institutions under the effective if not absolute control of an incumbent leader, changes in government through fair and honest elections become all but impossible.

Unlike Soviet-style communism, modern authoritarianism is not animated by an overarching ideology or the messianic notion of an ideal future society. Nor do today’s autocrats seek totalitarian control over people’s everyday lives, movements, or thoughts. The media are more diverse and entertaining under modern authoritarianism, civil society can enjoy an independent existence (as long as it does not pursue political change), citizens can travel around the country or abroad with only occasional interference, and private enterprise can flourish (albeit with rampant corruption and cronyism).

This study explains how modern authoritarianism defends and propagates itself, as regimes from different regions and with diverse socioeconomic foundations copy and borrow techniques of political control. Among its major findings:

- Russia, under President Vladimir Putin, has played an outsized role in the development of modern authoritarian systems. This is particularly true in the areas of media control, propaganda, the smothering of civil society, and the weakening of political pluralism. Russia has also moved aggressively against neighboring states where democratic institutions have emerged or where democratic movements have succeeded in ousting corrupt authoritarian leaders.

- The rewriting of history for political purposes is common among modern authoritarians. Again, Russia has taken the lead, with the state’s assertion of authority over history textbooks and the process, encouraged by Putin, of reassessing the historical role of Joseph Stalin.

- The hiring of political consultants and lobbyists from democratic countries to represent the interests of autocracies is a growing phenomenon. China is clearly in the vanguard, with multiple representatives working for the state and for large economic entities closely tied to the state. But there are also K Street representatives for Russia, Kazakhstan, Azerbaijan, Turkey, Ethiopia, and practically all of the authoritarian states in the Middle East.

- The toxic combination of unfair elections and crude majoritarianism is spreading from modern authoritarian regimes to illiberal leaders in what are still partly democratic countries. Increasingly, populist politicians—once in office—claim the right to suppress the media, civil society, and other democratic institutions by citing support from a majority of voters. The resulting changes make it more difficult for the opposition to compete in future elections and can pave the way for a new authoritarian regime.

- An expanding cadre of politicians in democracies are eager to emulate or cooperate with authoritarian rulers. European parties of the nationalistic right and anticapitalist left have expressed admiration for Putin and aligned their policy goals with his. Others have praised illiberal governments in countries like Hungary for their rejection of international democratic standards in favor of perceived national interests. Even when there is no direct collaboration, such behavior benefits authoritarian powers by breaking down the unity and solidarity of the democratic world.

- There has been a rise in authoritarian internationalism. Authoritarian powers form loose but effective alliances to block criticism at the United Nations and regional organizations like the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe and the Organization of American States, and to defend embattled allies like Syria’s Bashar al-Assad. There is also growing replication of what might be called authoritarian best practices, vividly on display in the new Chinese law on nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and efforts by Russia and others to learn from China’s experience in internet censorship.

- Modern authoritarians are working to revalidate the concept of the leader-for-life. One of the seeming gains of the postcommunist era was the understanding that some form of term limits should be imposed to prevent incumbents from consolidating power into a dictatorship. In recent years, however, a number of countries have adjusted their constitutions to ease, eliminate, or circumvent executive term limits. The result has been a resurgence of potential leaders-for-life from Latin America to Eurasia.

- While more subtle and calibrated methods of repression are the defining feature of modern authoritarianism, the past few years have featured a reemergence of older tactics that undermine the illusions of pluralism and openness as well as integration with the global economy. Thus Moscow has pursued its military intervention in Ukraine despite economic sanctions and overseen the assassination of opposition figures; Beijing has revived the practice of coerced public “confessions” and escalated its surveillance of the Tibetan and Uighur minorities to totalitarian levels; and Azerbaijan has made the Aliyev family’s monopoly on political power painfully obvious with the appointment of the president’s wife as “first vice president.”

- Modern authoritarian systems are employing these blunter methods in a context of increased economic fragility. Venezuela is already in the process of political and economic disintegration. Other states that rely on energy exports have also experienced setbacks due to low oil and gas prices, and China faces rising debt and slower growth after years of misallocated investment and other structural problems. But these regimes also face less international pressure to observe democratic norms, raising their chances of either surviving the current crises or—if they break down—giving way to something even worse.

In subsequent sections, this report will examine the methods employed by authoritarian powers to neutralize precisely those institutions that were thought to be the most potent weapons against a revitalized authoritarianism. The success of the Russian and Chinese regimes in bringing to heel and even harnessing the forces produced by globalization—digital media, civil society, free markets—may be their most impressive and troubling achievement.

Modern authoritarianism is particularly insidious in its exploitation of open societies. Russia and China have both taken advantage of democracies’ commitment to freedom of expression and delivered infusions of propaganda and disinformation. Moscow has effectively prevented foreign broadcasting stations from reaching Russian audiences even as it steadily expands the reach of its own mouthpieces, the television channel RT and the news service Sputnik. China blocks the websites of mainstream foreign media while encouraging its corporations to purchase influence in popular culture abroad through control of Hollywood studios. Similar combinations of obstruction at home and interference abroad can be seen in sectors including civil society, academia, and party politics.

The report draws on examples from a broad group of authoritarian states and illiberal democracies, but the focus remains on the two leading authoritarian powers, China and Russia. Much of the report, in fact, deals with Russia, since that country, more than any other, has incubated and refined the ideas and institutions at the foundation of 21st-century authoritarianism.

Finally, a basic assumption behind the report is that modern authoritarianism will be a lasting feature of geopolitics. Since 2012, both Vladimir Putin and Xi Jinping have doubled down on existing efforts to stamp out internal dissent, and both have grown more aggressive on the world stage. All despotic regimes have inherent weaknesses that leave them vulnerable to sudden shocks and individually prone to collapse. However, the past quarter-century has shown that dictatorship in general will not disappear on its own. Authoritarian systems will seek not just to survive, but to weaken and defeat democracy around the world.

Modern Authoritarianism

The traditional authoritarian state sought monopolistic control over political life, a one-party system organized around a strongman or military junta, and direct rule by the executive, sometimes through martial law, with little or no role for the parliament.

Traditional dictatorships and totalitarian regimes were often defined by closed, command, or autarkic economies, a state media monopoly with formal censorship, and “civil society” organizations that were structured as appendages of the ruling party or state. Especially in military dictatorships, the use of force—including military tribunals, curfews, arbitrary arrests, political detentions, and summary executions—was pervasive. Often facing international isolation, traditional dictatorships and totalitarian regimes forged alliances based on common ideologies, whether faith in Marxist revolution or ultraconservative, anticommunist reaction.

As the 20th century drew to a close, the weaknesses of both communist systems and traditional dictatorships became increasingly apparent. Front and center was the growing economic gap between countries that had opted for market economies and regimes that were committed to statist economies.

The political and economic barriers that had long sheltered the old dictatorships were soon swept away, and those that survived or recovered did so by making a series of strategic concessions to the new global order.

Modern authoritarianism has a different set of defining features:

- An illusion of pluralism that masks state control over key political institutions, with co-opted or otherwise defanged opposition parties allowed to participate in regular elections

- State or oligarchic control over key elements of the national economy, which is otherwise open to the global economy and private investment, to ensure loyalty to the regime and bolster regime claims of legitimacy based on economic prosperity

- State or oligarchic control over information on certain political subjects and key sectors of the media, which are otherwise pluralistic, with high production values and entertaining content; independent outlets survive with small audiences and little influence

- Suppression of nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) that are focused on human rights or political reform, but state tolerance or support for progovernment or apolitical groups that work on public health, education, and other development issues

- Legalized political repression, with targets punished through vaguely worded laws and politically obedient courts

- Limited, selective, and typically hidden use of extralegal force or violence, with a concentration on political dissidents, critical journalists, and officials who have fallen from favor

- Opportunistic, non-ideological cooperation with fellow authoritarian states against pressure for democratic reform or leadership changes, international human rights norms and mechanisms, and international security or justice interventions

- Knowledge-sharing with or emulation of fellow authoritarian states regarding tactics and legislation to enhance domestic control

Breaking Down Democracy | Freedom House

https://freedomhouse.org/report/special-report/2017/breaking-down-democracy

Selection of Leaders

One of the most basic features of a democracy that sets it apart from authoritarianism is the process by which leaders are chosen. Because democracy is meant to uphold the power of the people, leaders are chosen such that they truly represent the people’s interests. This is done through fair and honest elections, whereby citizens may collectively express their choice of leaders through the ballot.

[Leaders] are thus chosen based on whom the electorate collectively selects, and the power of the leader stems from this mandate.

To ensure the integrity of elections, they are administered by a neutral party, with independent observers for the voting and counting processes, and citizens must be able to vote in confidence, without intimidation or fear of violence.

An election governed by citizens’ choice is designed so that elected representatives are those who truly listen to their people and aim to address their needs. Held at regular intervals, elections furthermore ensure that those in power cannot extend their term without the consent of the people.

In an authoritarian state, such mechanisms are rendered either obsolete or futile. Dictators want to cling to power, and so the very notion of an election is counter to that desire. Thus, authoritarian states often do away with elections entirely, taking the choice away from the people to begin with. In more insidious cases, dictators engage the electoral process but dishonestly. By rigging the system, while offering their citizens the illusion of choice, the staged elections only serve to legitimize the dictator’s continued rule, as it continues to seem as if the dictator enjoys the support of the public.

Civic Participation

Beyond the selection of leaders, another feature that differentiates democracies from authoritarian states is the level of civic participation that is expected and allowed.

- Democracies favor, and in fact thrive on, the active participation of its citizens in the political landscape, whereas

- Dictators quash even the possibility of genuine participation.

In democracies, citizens are encouraged to participate by being informed about public issues, and freely expressing their opinions on these issues, as well as the decisions of their elected representatives. Citizens are likewise given the power to shape these decisions by being active members of civil society and non-government organizations. Even on the level of voting wisely in elections, and thereby choosing what interests should be prioritized in governance, citizens may actively participate in the exercise of power. Across these means of participation, citizens are enjoined to participate peacefully, respectfully toward the law, and with sensitivity to the plurality of views that exist in society.

Authoritarian states reject these modes of participation; and indeed, participation in principle. Public dissent is deemed public rebellion, a threat to the dictator’s unopposed tenure in power, and dictators inflict state violence to silence such opposition. Meanwhile, decision-making is limited to the dictator’s wishes as well, such that they may enact laws and decrees for the benefit of his own interest without appropriate mechanisms to keep their actions in check—no laws to limit them, no plurality to take into consideration.

Fundamental Liberties

Finally, what sets democracies apart from authoritarianism is their treatment of fundamental liberties. Truly democratic societies are those which respect and uphold the fundamental liberties of all their citizens, regardless of who they are. These liberties include the basic freedoms of expression, religion, assembly, and the press, as well as basic rights such as the right to privacy, to due process, and to life.

A dictator, on the other hand, does not respect these freedoms and rights. This is because these freedoms and rights typically make the dictator vulnerable to criticism, to the exposure of their abuses, and ultimately to the limits of their power. Because our fundamental liberties apply equally to all, they must apply equally to the dictator and ordinary citizens, whoever they may be. A dictator, therefore, often ignores or even violates these rights, to perpetuate themselves in power. So long as they can convince the populace that they are more important than everyone else, and subject to a different standard, they allow themselves that much more room to act with impunity...

Authoritarian Strongmen Tyrants

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QrfbtUpWOsc

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZKBzdN3jUho

China: Socialism or Capitalism?

Polish Presidential Election Explained What it Means for Europe

How Democracy Ends review – is people politics doomed?

Author: Andrew Rawnsley

Some people sniff the air and smell an alarmingly foul whiff of the 1930s. The rise of demagogues and “strongmen”; the resurgence of authoritarianism, nationalisms and fundamentalisms; the denigration of expertise and the celebration of ignorance; scorn for consensus-builders and pragmatic compromise; the polarisation of politics towards venom-spitting extremes. Haven’t we seen this horror movie before?

No, argues David Runciman in this scintillating treatise about representative democracy and its contemporary discontents.

Donald Trump is “an old man with the political personality of a child”, but he is not “a proto-Hitler”.

We are not reliving the first half of the 20th century in Europe.

Vladimir Putin presides over a “parody democracy” in Russia, but he is not Stalin.

Some of the symptoms of democratic decay may seem familiar, but the disease is different. We make a potentially fatal mistake if we think that history is just repeating itself. Gaze obsessively into the rear-view mirror and we won’t see the true threats on the road ahead.

He is right to register “widespread contemporary disgust with democratic politics”. Some of the sources that he identifies will be familiar to readers of the burgeoning literature on the malaise afflicting the more mature democracies. Voter confidence has been sapped by governments that struggle to deliver the underlying contract to spread prosperity sufficiently widely and fairly that everyone has the sense of a stake in society. It is not surprising that many Americans were discontented enough to choose the wild ride of Trump when you consider that the average real wage in the United States has been stagnant for the past 40 years. The internet, far from being the elixir of democratic accountability and engagement that utopians once imagined, has poisoned the well. Opposed sects promote conspiracy theories in their rival echo bubbles rather than engage in reasoned debate around an agreed set of facts. Democracy has become more venomous – and at the same time more toothless. Governments flounder in the face of the disruption unleashed by the tech titans of Silicon Valley and subverters tilling the troll farms run out of the Kremlin. Short-termist politicians are inadequate to the task of tackling existential threats to humanity, such as climate change, because thinking about the end of the world “is too much for democracy to cope with”.

Runciman is gloomy because one of his key contentions is that representative government has lost the capacity to reinvigorate itself. In the opening decades of the 20th century, support for democracy was widened by extensions to the franchise and the foundation of welfare states. He offers the provocative thought that democracy also thrived – even depended upon – “chaos and violence” because they “bring the best out in it”. The second world war demonstrated the benefits of democracy when confronted by nazism. The cold war – this is my suggestion, not his – advertised why liberal capitalist democracy was superior to totalitarian communism.

For all its flaws, where democracy has enough time to put down roots it proves durable. He offers the example of Greece, a country that was ruled by a military junta within living memory. Despite a series of flailing governments presiding over a dire economic situation that has inflicted enormous stress on the population, the Greek military has not put a bootcap out of its barracks.

Yet Runciman finds this not a reason to be cheerful, but another cause for concern. A thought-stimulating strand of his case is that the resilience of the mature democracies is at the heart of their failings. “Stable democracies retain their extraordinary capacity to stave off the worst that can happen without tackling the problems that threatened disaster in the first place.” Despite the look-at-me title of the book, he doesn’t think democracy is over. Rather, he contends it is suffering a “midlife crisis”. In the American iteration, “Donald Trump is its motorbike”. His presidency could end in “a fireball” but it is more likely to be looked back at as a phase of decline that is “simply embarrassing”.

For all its manifest and manifold imperfections, democracy has a better record than any rival form of government

Runciman’s flair for turning a pithy and pungent phrase is one of the things to admire about his writing. The cogency, subtlety and style with which he teases out the paradoxes and perils faced by democracy makes this one of the very best of the great crop of recent books on the subject. What he doesn’t offer is solutions, bluntly admitting “I do not have any”. There is penetrating diagnosis here, but no suggestion of a cure. He considers the alternatives and rightly finds them wanting. The Chinese experiment with authoritarian capitalism may look seductive to those who think economic expansion is all that matters to a society, but can the repressive Beijing model survive the inevitable day when growth slows down? Government by experts, “the rule of the knowers” or “the epistocracy”, was advocated by Plato and is still promoted by those who regard citizens as too stupid to be trusted with making decisions. The public wouldn’t wear that and “intellectuals” are just as prone to making terrible mistakes as the crowd. Runciman seems attracted to the idea that technological advances could offer some form of “liberation”, but comes to the equivocal conclusion that this “includes all sorts of potential futures: some wondrous, some terrible, and most wholly unknowable”.

I share a lot of his anxieties, but ultimately he didn’t persuade me to subscribe to his underlying despair. For all its manifest and manifold imperfections, democracy has a better record than any rival form of government at sustaining free, innovative, peaceful and prosperous societies. Yes, democracy is often messy, clumsy and ineffectual. Yes, voters sometimes empower ghastly rulers. Yes, democracy is looking tired at this moment in its history. But almost despite himself, and without saying it this explicitly, Runciman seems to accept that there is something special about democracy. One of its great merits is the capacity for self-questioning and self-correction, which is lacking in other systems of government whether they be tyranny by emperor, colonel, president of the praesidium, priests or data. Democracy can go wrong, but it has the flexibility to put itself right. As Runciman acknowledges, “democratic politics assumes there is no settled answer to any question” and this “protects us against getting stuck with truly bad ideas”. As Tocqueville put it: “More fires get started in a democracy, but more fires get put out too.”

I finished this book feeling more hopeful than I thought I would be and the author probably expects his readers to be. Democracy can change its mind and by doing so it can improve its circumstances and prospects. This is a precious quality that contains within it the possibility of renewal. Donald Trump is not the end of democracy’s story.

How Democracy Ends by David Runciman

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2018/may/20/how-democracy-ends-david-runciman-review-trump

with Trump, there is no shared reality

Surviving Autocracy is about the Trump phenomenon and how it has transformed US society. It is about what he has learned from Vladimir Putin, among other autocrats he admires. It is also one of the few analytical books to suggest plausible ways he might be stopped.

The People vs. Democracy: Why Our Freedom Is in Danger and How to Save It

The world is in turmoil. From Russia, Turkey, and Egypt to the United States, authoritarian populists have seized power. As a result, democracy itself may now be at risk.

Two core components of liberal democracy―individual rights and the popular will―are increasingly at war with each other. As the role of money in politics soared and important issues were taken out of public contestation, a system of “rights without democracy” took hold. Populists who rail against this say they want to return power to the people. But in practice they create something just as bad: a system of “democracy without rights.” The consequence, as Yascha Mounk shows in this brilliant and timely book, is that trust in politics is dwindling. Citizens are falling out of love with their political system. Democracy is wilting away. Drawing on vivid stories and original research, Mounk identifies three key drivers of voters’ discontent: stagnating living standards, fear of multiethnic democracy, and the rise of social media. To reverse the trend, politicians need to enact radical reforms that benefit the many, not the few.

The People vs. Democracy is the first book to describe both how we got here and what we need to do now. For those unwilling to give up either individual rights or the concept of the popular will, Mounk argues that urgent action is needed, as this may be our last chance to save democracy.

https://www.amazon.com/People-vs-Democracy-Freedom-Danger/dp/0674976827

The Demon in Democracy: Totalitarian Temptations in Free Societies

Ryszard Legutko lived and suffered under communism for decades--and he fought with the Polish ant-communist movement to abolish it. Having lived for two decades under a liberal democracy, however, he has discovered that these two political systems have a lot more in common than one might think. They both stem from the same historical roots in early modernity, and accept similar presuppositions about history, society, religion, politics, culture, and human nature.

In The Demon in Democracy, Legutko explores the shared objectives between these two political systems, and explains how liberal democracy has over time lurched towards the same goals as communism, albeit without Soviet style brutalality.

Both systems, says Legutko, reduce human nature to that of the common man, who is led to believe himself liberated from the obligations of the past. Both the communist man and the liberal democratic man refuse to admit that there exists anything of value outside the political systems to which they pledged their loyalty. And both systems refuse to undertake any critical examination of their ideological prejudices.

https://www.amazon.com/Demon-Democracy-Totalitarian-Temptations-Societies/dp/1594039917/

How to Be a Dictator by Frank Dikötter review – the cult of personality

Born in obscurity, frustrated in youth, the dictator rises through accident, patronage or anything except merit to blossom into a fully fledged evil-doer, desperate for the respect and admiration that are wrung from the populace only by skilled PR manipulation. Often feigning modesty, he soon generates a cult that he personally develops. Women and even brave men feel overcome in his presence; schoolchildren chant the praise of the father of the nation; artists and writers deify the great leader. Dictators generally come equipped with an ideology, but since they have no principles, only a lust for power, the process of propagation turns it into a mockery.

Although dictators often fancy themselves as writers or philosophers, they fail to make the grade as intellectuals, and the Little Red Books they produce are travesties. If they are dictators of the left, their attempts at radical reform bring famine and suffering to the population. If dictators of the right, they go to war, with the same consequence of popular suffering, and lead the nation to shameful defeat. They long to be popular, and put great effort into creating that illusion, but it is all fakery. Surrounded by sycophants, they are friendless, lonely and paranoid. Most of them die a dog’s death, but if they somehow manage to avoid this, people only pretend to mourn them. After their death, they are quickly forgotten.

This is the collective portrait that emerges from Frank Dikötter’s book, the eight chapters of which deal with Mussolini, Hitler, Stalin, Mao Zedong, Kim Il-sung, Haiti’s “Papa Doc” Duvalier, Romania’s Nicolae Ceauşescu and Ethiopia’s Mengistu Haile Mariam. Despite their fundamental similarities, his dictators do have stylistic differences. Stalin allowed streets and cities to be named after him, while Mao did not. Hitler was a teetotaller and Duvalier a follower of the occult. Kim’s floodlit statue towered over Pyongyang, following the tradition of Stalin statues, but Hitler vetoed the construction of statues of himself (thinking this honour should be reserved for great historical figures), and Ceauşescu and Duvalier felt the same. Some dictators’ enforcers wore brown shirts, others black, and still others had no uniform. Mussolini and Hitler excelled as orators, while Stalin was an undistinguished speaker who never addressed mass rallies. Stalin, Mao and Duvalier wrote poetry, Hitler painted and Mussolini played the violin.

In the chapters on the “big” dictators – Mussolini, Hitler, Stalin and Mao – Dikötter dwells on the cult that developed round them. All of them headed a party that borrowed some of their charisma, and their regimes featured a variety of secret police and enforcers as well as cheerleaders and informers. Ordinary people were encouraged to believe that anything bad was done by subordinates without the dictator’s knowledge (“If only the Duce/Fūhrer/vozhd’ knew”). In fact, the dictators repeatedly made terrible mistakes and appear to have had few if any lasting achievements. With Mao and Stalin, the “dog’s death” trope doesn’t quite fit, but Dikötter runs a modified form of it anyway. Dying, Stalin lay unattended, “soaked in his own urine”, and “one month after his funeral”, his “name vanished from the newspapers”.

Dikötter’s sources are impressive, including 16 archives from nine countries, one of them being the former Soviet Central Party Archive (now renamed RGASPI) in Moscow. Despite this, I did not find the Stalin chapter particularly compelling, no doubt partly because I do not share the author’s view that the cult is the most interesting thing about Stalin. When Dikötter writes that the dry-as-dust Short Course on the History of the All-Union Communist Party, in whose composition Stalin participated, “deified Stalin as the living fount of wisdom”, I wonder if he has actually read it.

For me, the most entertaining chapters of this book were about the dictators I was least familiar with. It is intriguing to read that the remains of Mengistu’s predecessor, Emperor Haile Selassie, were possibly “buried underneath his office, placing his desk right above the corpse”. The stand-out dictator, in terms of entertainment value, is Duvalier, with his personal militia the Tonton Macoutes, who “dressed like gangsters, with shiny blue-serge suits, dark, steel-rimmed glasses and grey homburg hats” for their enforcement duties. Duvalier modelled himself on Baron Samedi, the Vodou spirit of the dead and guardian of cemeteries, and sometimes dressed the part, all in black, with top hat and carrying a cane. Dikötter characterises him as a “dictator’s dictator”, by which I think he means the stripped-down model with “no true party” and without the “pretence of ideology”. Certainly Duvalier has a claim to be the reductio ad absurdum.

He is one of two dictators in the book with dynastic ambitions for their sons, the other – and more successful over the long term – being Kim. That seems to me an important difference from the others, including all the “big” ones, but Dikötter does not remark on it. Overall, his argument is that dictators’ cults are not peripheral phenomena but lie “at the very heart of tyranny”. He holds that, contrary to widespread belief, the dictators had not “captured the souls of their subjects and … cast a spell on them”. “There never was a spell. There was fear, and when it evaporated the entire edifice collapsed.” This seems a strange conclusion when it comes to Stalin, whose successors wrestled with his legacy for decades, and an even stranger one for Mao, the dictator closest to Dikötter own field of expertise. But denying any contemporary popularity or lasting impact to the dictators seems to be the main point of the book.

While Dikötter is explicitly dealing with 20th-century dictators, the stage is set in the preface by France’s 18th-century Sun King, Louis XIV, a great practitioner of political theatre, remembered for his aphorism “L’État, c’est moi”. But if Louis was a model for any of the 20th-century dictators, we don’t hear of it in this book. For that matter we learn little about whom the dictators modelled themselves on (or against) and how they reacted to each other. Yet surely Mussolini, Hitler and Stalin kept an interested eye on each other’s PR practices and on occasion quietly imitated them; and Mao was scarcely indifferent to Stalin’s example.

Questions of chronology, sequence and influence are not much discussed here. The mid 20th century is generally considered the heyday of dictators of the right and the left, but Dikötter does not explore why this might have been so, and even obscures the issue by including chronological outliers such as Mengistu. It is important to study dictators, he suggests, because they are an eternal threat to democracy and freedom – but not, it seems an acute current threat. “Dictators today, with the exception of Kim Jong-un, are a long way from instilling the fear their predecessors inflicted on their population at the height of the twentieth century … Even a modicum of historical perspective indicates that today dictatorship is on the decline.” That’s reassuring. Perhaps it would be churlish to ask how we got so lucky.

How to Be a Dictator is published by Bloomsbury

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2019/oct/26/how-to-be-dictator-frank-dikotter-review

Abstract